In the iconic scene of the Stanley Kubrick dystopian movie, A Clockwork Orange, Alex the antihero is jailed for a violent murder and agrees to undergo an experimental therapy for rehabilitation. Alex’s eyes are forced to stay open by cold, metal clamps to watch films featuring sex and violence while being strapped to the chair, unable to turn his head or stop the images from hitting his visual circuitry. Meanwhile, he is injected with nausea-inducing drugs so that he associates violence with getting sick. As soon as he begins to robotically behave within the rules of society, the government declares him “cured.” He becomes a “clockwork orange,” organic flesh and blood on the outside, cold and mechanical on the inside.

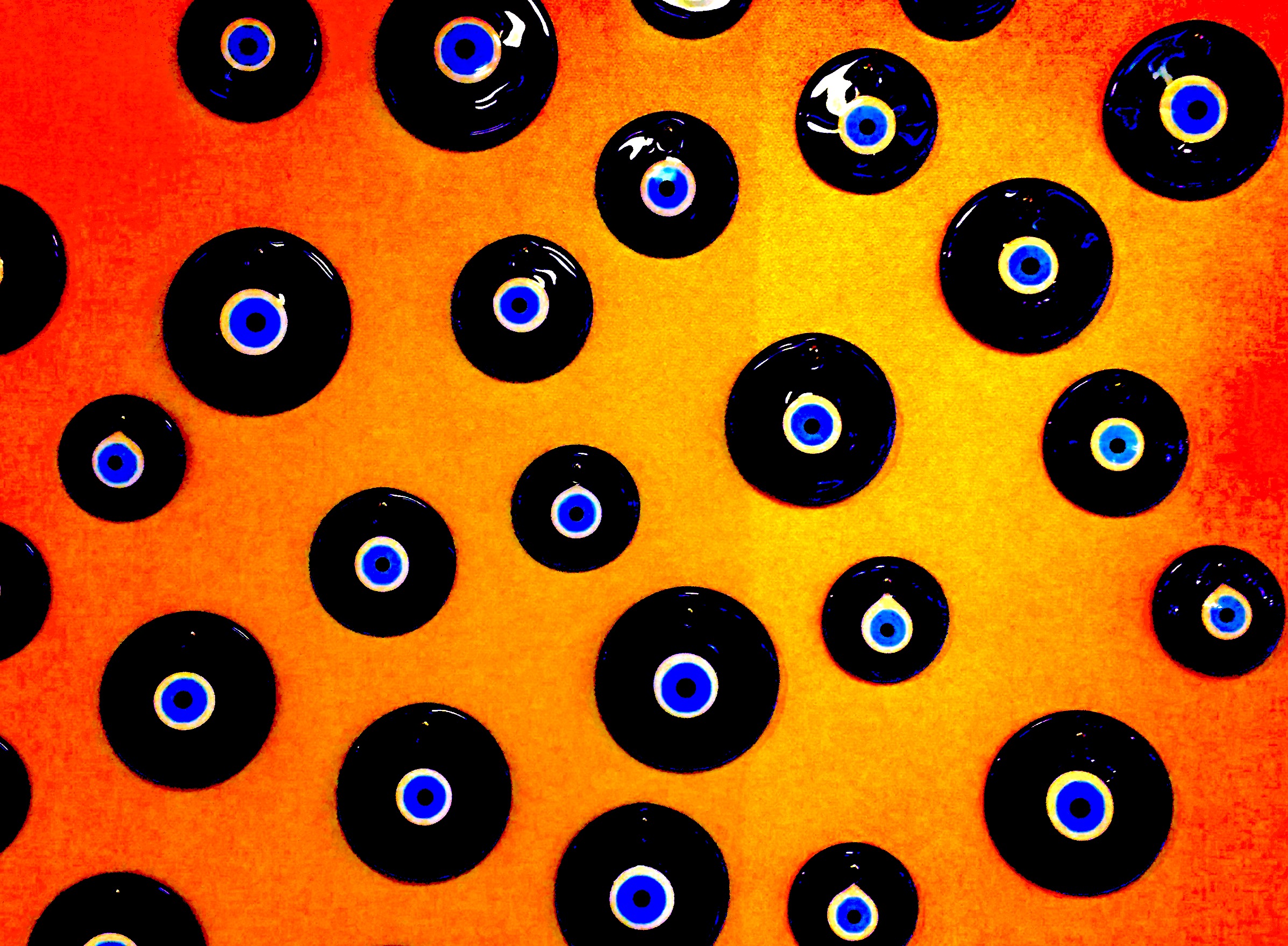

In both the digital and analog world, we can appear salubrious, dripping with knowledge and oozing with energy. Yet perhaps, sometimes, even the most well-intentioned of us become robotic. We become so comfortable with what we know, we move on autopilot. We post articles about the need to build bridges with the “Other” while rolling our eyes at anyone who strays too far from our comfort zone. We post photos of embracing the beauty of nature while we disturb the landscape for our “money shot.” We speak about truth while we bully on Zoom. We fool ourselves into thinking we were awake, our eyes wide open, when in fact, we may be moving on autopilot, ignoring those outside our bubble, sleepwalking through life.

Whether you think we are headed toward a dystopian future or not, there is little question that industries from all sectors are calling for disruption because much of the way we have been is no longer working. The global pandemic has made that loud and clear. It has laid out bare for all to see. While half the world bemoans doing math equations on Zoom, the other half still cannot access any online learning easily. Over 700 million school-age children do not have internet at home, and even then, over 820 million children do not have a computer at home.

Even before the pandemic, the divide between who has access to what and how much and who doesn’t was evident. In our drive for survival and success, it is easy to focus on our individual needs and wants, and to see others as the “Other.” Low-income students are undermatched when it comes to college; Teacher of the Years have second or third jobs because of budget cuts. Institutions of higher education face massive financial loss, if not closure. Millions without health care or sick leave or a living wage. Throw in a pandemic, and well, here we are, having not only our eyes forced wide open, but also arousing our minds from a slumber of blissful avoidance.

Or are they?

As we start figuring out the New Normal – whatever that is – we seek guidance from those who “know.” Without knowing what the “right” answer is, we call in the experts and the so-called experts that speak our language. We convene. We convene like-minded people. We talk. We talk at people about the 1,001 things that are wrong. We sit on panels. We sit on panels with people who agree with us. We raise questions. We raise questions about who, why, what. We build coalitions to seek answers. We build coalitions to convene like-minded people who will talk to each other about the urgent things our planet and our humanity need addressing, and raise the questions about who, why, what.

Few gatherings engage a truly intersectional, intergenerational spectrum of voices and experiences, much less invite this spectrum to the decision-making table. Many panels of experts rightfully consist of people who know and do the work. Yet many have similar backgrounds offering a slightly different viewpoint, talking to – not with – an audience. They entertain a few questions, but those questions are not invitations to join the table. After all, what can a plumber “teach” a tech wiz? What can a high school student “teach” an expert in mergers and acquisitions? What can a “gasp – ordinary” citizen “teach” a PhD in quantum physics? It isn’t uncommon that those who often are in need of hearing from these voices are the first to leave the room because they “already know it all.”

We end up with eyes wide open, mind asleep, simply hearing what we already know. It may seem like we are engaging the full human spectrum of experience and perspective, but in reality, we’re still hostage to the limitations of our bubbles. We’ve become passive to our own voices and those like us. Perhaps we need to also wake our minds up and listen to others who we don’t easily see anything in common, those whose voices have been silent. Not easy to do.

So, where to start?

- Have empathy

Even those of us who thrive on innovation forget to be truly empathetic. Some design thinking processes, for example, begin with empathizing with the “end user.” Yet many of these processes skip the teaching of empathy. How might we cultivate human connection as a place to begin dialogue? To understand that while our behaviors may be inconceivable to others, and vice versa, we are mostly driven by the same fears and desires.

- Check biases

We all have them. If we do not pay attention and raise awareness of our own biases and filters, we become less able to see and invite other perspectives that may be critical to finding possible answers. Yet these are the skills that are critical to disrupting things that no longer work. Rather than pretend “we-don’t-see-X,” being honest about what they are allow us to work through them.

- Invite belonging

Let’s honor and celebrate all the different ways our strengths and skills show up, and how each one of us have a critical role to play in a better tomorrow. Not as lip service, but truly recognizing each person’s authenticity with compassion and equanimity. It’s not just a matter of having X or Y person to represent the “voice of,” but creating the space where all belong – and are wanted – at the table because, not despite, of their differing points of views.

Sitting on a panel with other talking heads can be incredibly enlightening. But if that’s all we do, if we do not invite the voices of others, if we become too convinced about “our” way of doing things or become too blind to our blind spots, we have strapped ourselves to the chair, eyes wide open, mind fast asleep.