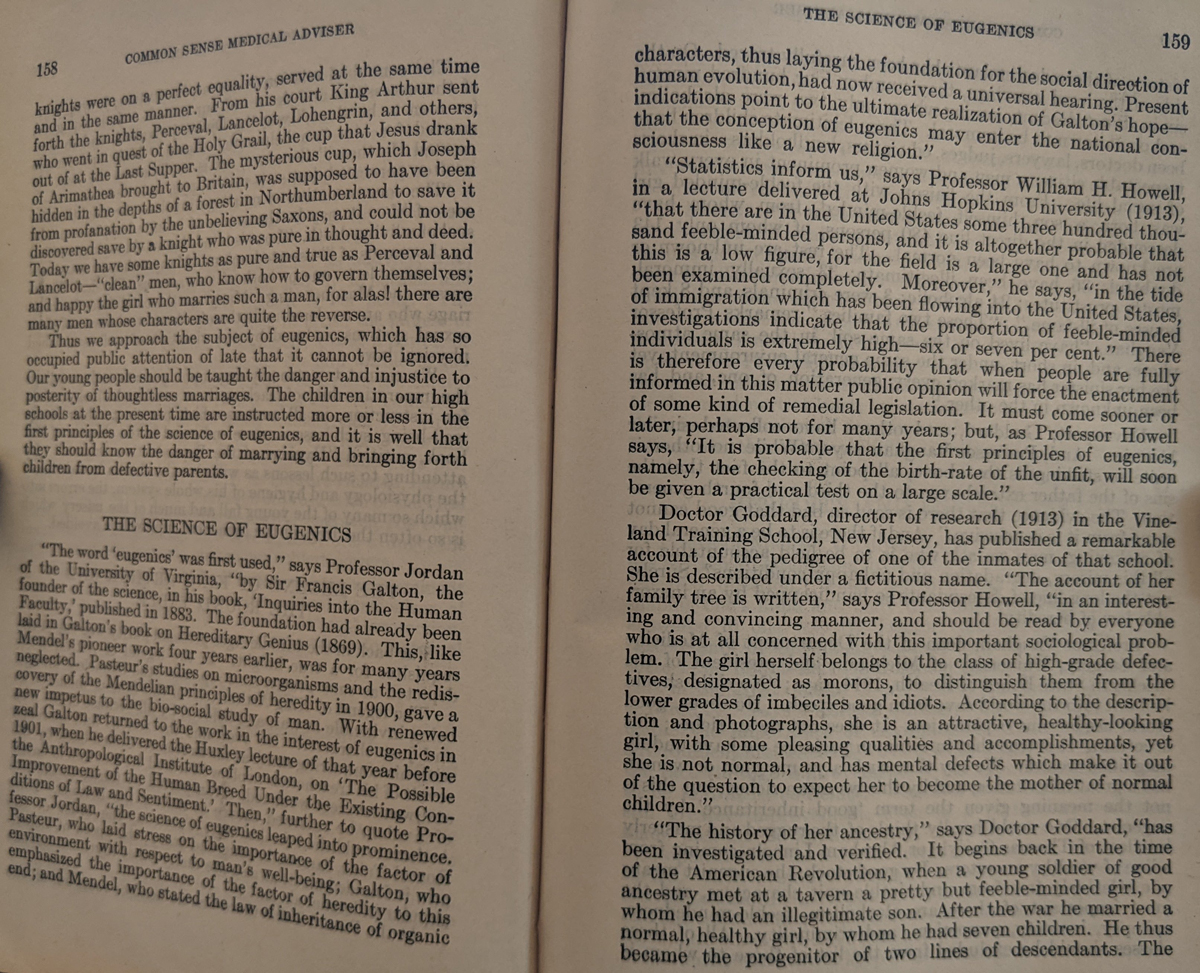

I came across a heading in an old medical book from 1918, The People’s Common Sense Medical Advisor by R. V. Pierce, MD, that read, “The Science of Eugenics.” This so-called academic discipline to improve the genetic quality of human populations was founded in 1883 by the renowned British heredity scientist, Sir Francis Galton. He headed the first University department of Eugenics at University College, London. In 1914, Professor Vaughan, Dean of the department of Medicine and Surgery at the University of Michigan trumpeted, “No child should be born into the world save of good stock…relatively free from undesirable unit characters, and the most important of these are alcoholism, feeble-mindedness, epilepsy, insanity, pauperism and criminality.” The elites of the time were heartily in favor of eugenics, as long as their own group was superior to others. The principles expounded were used to justify slavery, indentured servitude, racial genocide and Hitler’s gas chambers. Today, eugenics would never be considered a science but rather a racist belief system.

In the seventeenth century, the Catholic Church had a stranglehold on scientific inquiry. Scientists had to conform to religious beliefs to avoid suffering the effects of being accused of heresy. In 1633, the Italian astronomer and physicist Galileo was tried by the Inquisition and put under house arrest for the rest of his life. His heretical crime was daring to suggest that rather than the sun orbiting the earth, it was the earth that rotated daily and revolved around the sun.

Few people have heard of the Hungarian obstetrician and scientist, Ignaz Semmelweis, a pioneer of antiseptic procedures. He discovered that the incidence of mothers dying in childbirth could be dramatically reduced if doctors washed their hands in disinfectant between patients. In 1847, while working in the Obstetrics Clinic of Vienna General Hospital, Semmelweis proposed a hand-washing regimen for doctors and had strong evidence to show that the practice drastically reduced mortality. The medical community rejected his findings. Many doctors ridiculed him, insulted by the idea that they needed to wash their hands. His colleagues, claiming that Semmelweis had a mental breakdown, threw him into a lunatic asylum where he died a broken man after being beaten by guards. It took about three decades for the handwashing practices that Semmelweis advocated to be taken up by the medical community.

The link between smoking and cancer was pooh-poohed by American doctors in the 1950s, some of whom instead talked about the health benefits of cigarettes. It took about half a century for America to fully accept that smoking was a health hazard and enact smoking bans. In 1996, Jeffrey Wigand, a biochemist and researcher for the tobacco firm, Brown and Williamson, blew the whistle about carcinogenic and addictive substances that the company had knowingly included in its products. As a result, he was fired from his job, faced a campaign to discredit his work and suffered harassment and death threats.

What history demonstrates is that the accepted scientific views of a specific period will be considered as totally fact-based by the majority of people at that time, and those who challenge the status quo may face severe consequences. Yet those views may well be debunked by a later generation of scientists. So is modern science objective, or just like eugenics and the 17th century view of astronomy, is it to some extent a belief system?

Just as Semmelweis found in the nineteenth century, and Wigand found in the 1990s, in the modern era, scientists who make claims that are contrary to established scientific and medical norms may find themselves discredited with their careers in tatters. Even if they have legitimate research supporting their claims, these might be debunked by competing studies. Science depends on research, but how accurate are the conclusions of studies that may be touted as definitive? There are important questions to ask when evaluating the quality of any study. How many participants were there? For what period of time were these participants followed? What were the ages of the participants? Were any participants dropped from the study? Was there a true control group? Was the study commissioned and/or carried out by an industry group or by a reputable independent agency or lab? A thorny issue is causation versus correlation. Has research found a link that is due to factors other than what has been studied? This is a valid point, but also a common way of discrediting a study that might throw light on an inconvenient truth.

When evaluating science and medicine as they stand today, an open mind and critical thinking are key. Some theories accepted as gospel by the scientific and medical community currently may in the not-too-distant future be seen as pure fiction—science fiction to be exact.

Photo © 2021 CJ Grace.