Turning 19, I was one month shy of completing my sophomore year at the University of San Francisco. I needed a summer job before transferring in the Fall to UC Berkeley. I needed a “real” job, different from the previous summer selling magazines door-to-door. The Jesuits at USF introduced me to the mystical wisdom of Ignatian spirituality and my soul was ripe for a summer experience filled with meaning and purpose. In the words of St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuit order, I was eager to “go forth and set the world on fire.”

My job search lead me to a 3” x 5” index card pinned on the bulletin board of USF’s College and Career Center: “Camp Counselor Wanted-No Experience Necessary. Contact Josephine Whitney Duveneck, Hidden Villa, Los Altos Hills, CA.” My interview with Josephine was in her home, Hidden Villa, located on 2,500 acres of land off Moody Rd. in the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains. We met at the “Big House, a 1930 Spanish- Mediterranean-style home set against a hill and overlooking the garden.

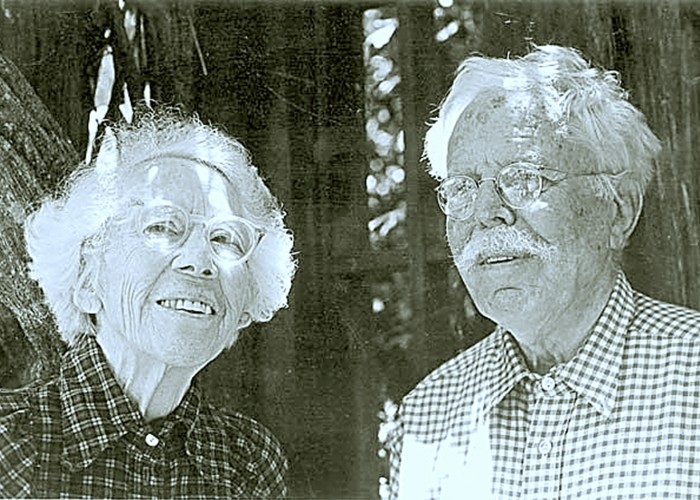

Josephine was 76 when I met her. She shared highlights of her life–raised a “Whitney” in Boston society; moving West in 1917 with her husband, Frank; exchanging an entitled life with one dedicated to social reform; purchasing the Hidden Villa property in the 1920’s; new approaches to aiding the plight of migrants; her friendship with Cesar Chavez and the joy of seeing at camp the children of the families who were in the Farmworker’s Movement and the California League for American Indians; sheltering Japanese-Americans returning from internment camps; establishing in 1937 the West’s first American youth hostel; and creating in 1945 the country’s first multi-cultural summer camp.

“IMMANENCE”

A MERGING OF THE OUTER AND THE INNER. NO LONGER TWO LEVELS OF LIFE, BUT A RECONCILIATION OF OPPOSITES

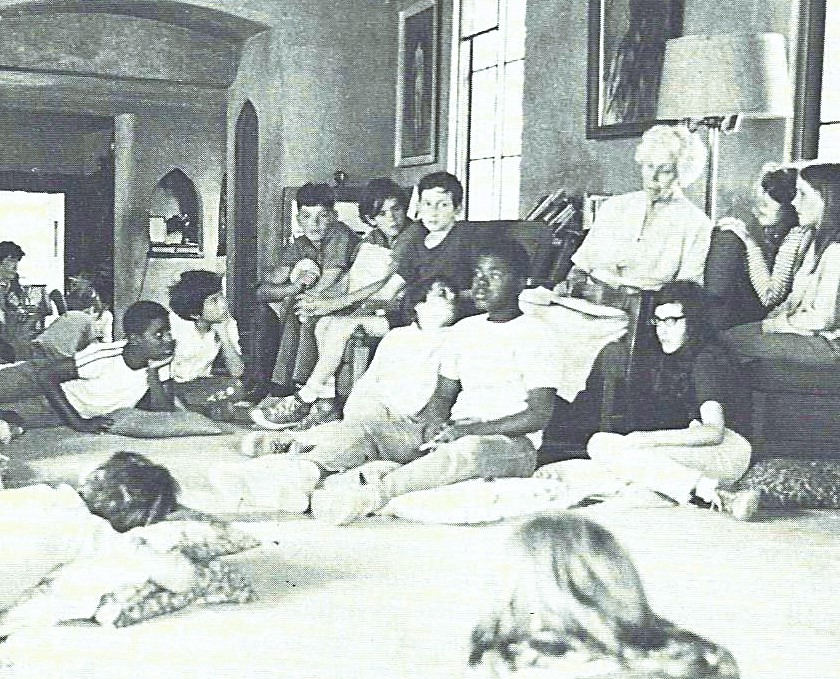

Josephine hired me for the summer. The week before she brought on another counselor with the first name Bob. So as not to cause confusion among the campers and staff, I would be known as “Rob” for the summer. This seemed like a small sacrifice for the opportunity to participate in Josephine’s grand program aimed at encouraging diversity, inclusion and combatting discrimination based on ethnicity, national origin, religion or sexual identity.

Campers from diverse economic and cultural backgrounds attended the camp. Josephine would underwrite the fees for the kids from the inner city. Her vision was that youth from these underserved communities would mingle with children from affluent areas in the Bay Area and both groups would learn from each other and create a bond of mutual respect. I saw first-hand that this social experiment worked and to this day this experience influences the work I do in community development, housing, and redeveloping communities.

Josephine died in 1978 at the age of 87, a few days after penning the final corrections to the manuscript of her autobiography, “Life on Two Levels, An Autobiography.” The legacy of Hidden Villa lives on today with the donation of the property after Frank’s death in 1985 to the state and its operation as a non-profit educational center focusing on experiential programs that value social and environmental justice and sustainability.

While I was at Berkeley, I returned to Hidden Villa to attend a Christmas reunion for campers and staff. I recall telling Josephine that I was going to graduate school in the Midwest and planned to combine my psychology degree and interest in social reform with a degree in urban planning and development. She smiled approvingly and brought into the discussion her experience of amassing the land for Hidden Villa in the 1920’s. She was quick to tell me how suburbanization was encroaching up Moody Rd. and there was a need to preserve Hidden Villa for future generations. That was the last time I saw Josephine.

The spirit of Josephine continues to live on in my heart whenever I read her autobiography. I learned from the Jesuits we encounter God in all places. Josephine carved a unique chapter of humanitarianism in early California history. She had a saintly and mystical quality about her that was distinctly Californian. I regard her as a “spiritual mentor” who captured my soul and continues to influence how I see the world in a new light and with new meaning. She planted in my soul the seeds to cultivate a vision for my life. She took a 19 -year old with “no experience” and bestowed upon him confidence and trust. For that, I am forever grateful.

This mystical summer experience set in motion an intentional vision for creating livable communities that serve the diverse and disadvantaged.