It’s not that hard to come up with new ideas.

If there’re a few things humans are greatly good at in marked comparison with other species, certainly, the ability to craft hundreds of different ideas and solutions for similar kinds of problems and be able to relate with them would come on top. Our vision is limitlessly diverse, and everything that falls into the diversity — from the creation of marvels to correspondence in relationships —provides rational explanations to what extent we can/will go to innovate.

In fact, we come up with new ideas every now and then, when we see something completely new or completely terrible, or when we dwell enough on where people wouldn’t look much. We even boil down an idea of someone else to create our own versions of it.

And then, if we think it’s good enough, we plan how to execute the idea.

Our executing ground could be a blog, or a movie, or a book, or a painting. The form of the art you are passionate about to convey your ideas to the world with hardly weighs against your potential. What matters, however, is getting to execute it.

The problem with seeing your idea come alive:

- All you have about what you are going to do is only a vision.

- The vision is beautiful.

- You think reality may not prove as good as the vision.

- Unless something can be done about it so that the vision can completely come off unrushed and perfect.

- The time it takes for your vision to come off unrushed and perfect is literally forever.

- You don’t have forever.

In hindsight perhaps, you might understand frustration is as much a part of the creation process as having a good idea is. Nothing you create will make you feel like it can’t be perfected more. There’s always going to be a part of your creation you had just let happen because you didn’t have any other way of putting it.

Successful people are often those who can see through their projects like that little blemish is not even there. They understand there’s always going to be a blemish, a deformity, or a tattered edge, and making it right in one place would tip the balance off on another.

They know the game, and maybe it’s not that hard to understand they’ve seen it work.

For the unsuccessful people, the blemish is right there in the centre even before they have started on their projects. And so they try to clear this imaginary blemish by building an imaginary castle to preserve their ideas under lock and key. The instant they let their ideas out in the open, there’s going to be immediate mucking up of the essence.

Now it becomes a jewel that’s so precious they’d rather not wear to the ball.

The purpose is lost.

The point is simple, and it is this: if you have an idea in your mind, don’t let it die of loneliness. If it isn’t as efficient, thought-provoking, life-changing, character-infusing as you thought it would be, then, maybe, let it die of impotence.

The “What You Should Know” part of this article falls into six major sub-headings:

- Imperfection Doesn’t Matter as Much as You Think It Does

- Take the Compulsion out of Your Purposeless Routines

- Saving the Best for Last Isn’t the Best Strategy

- Indecision Shouldn’t Bother Your Long Term Goals

- The Icebreaker

- Rise With Your Creative Flow

Imperfection Doesn’t Matter as Much as You Think It Does

If you only want the most perfect out of whatever you do, you better be having your definition of “perfection” right. That is going to define a great part of your productive career.

In the strive for the absolute best, you often wage toward what you have as standards for “perfection”, what you think perfection looks like, that often exceeds what you could get done in a respectable amount of time.

The problem is, there is no officially accepted standard that could be agreed on to be the best way to measure the level of perfection required. And what you measure yourself against is often like chasing the 4’o clock shadow of your greatest fantasies while facing away from the light of your passion.

It is a trick you pull on yourself to keep you working intensely around your goals and feel like gaining fast results while staying ignorant of the one direct path you could rather have taken for easy, dedicated achievement.

Perfection solidifies your fears about the worst thing that could happen to you in the process of creating. The bigger you have the “no man’s land” between stages of editing and publishing your work, the longer the battle is going to drag, and the more chance of getting your productivity killed.

Thomas Oppong wrote in his article about perfection, “The lack of perfection does not mean a lack of quality.” Although immense levels of perfection can make your work known for better quality than others with an incidental drawl, it’s hard to know when you should stop if you are hell-bent on filtering only the best through. More often than not, you get the result over-cooked with spices that are beyond the context. There was a point you should have stopped to have arrived at better quality than what perfection had you believe.

If you put all your thoughts in a balloon and began to blow it with the air of your “perfection”, you are either going to overdo it and get it blown, or going to under-do it enough to miss the point of a balloon.

All the while, you are ready to expend all your resources and time. The more perfect you want your work to be, the more time you think it should require.

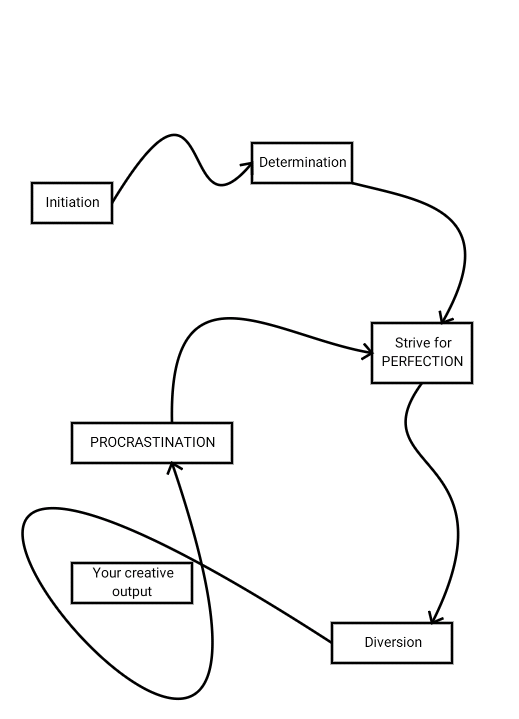

Everything then lands on a sophisticated paradox:

Procrastination destroys creativity, but you love your creativity so much you want it to come out the most perfect — the very want of which shuns you from actually doing stuff, and takes you back to procrastinating. What you thought should help you grow is the same reason you’re not.

On “How Perfectionism Is Destroying Your Productivity”, Darius Foroux wrote, “If you’re a perfectionist, you’re just a procrastinator with a mask.”

No matter how tough or easy it’s going to be, how long or short it’s going to need to get done, how much of it you are actually prepared for or not, if you are a perfectionist, it is going to be tough and take you so long that you are never prepared for it.

Procrastination becomes as much an excuse for perfection as perfection does for procrastination. They are not reciprocals that cancel each other out when required, rather, they are complements that tend to compound the effect.

And the worst thing that could happen to you?

When you procrastinate enough on getting something started, there comes a point when you develop a sense of maturity over it, when what appealed you at the time you coughed up the initiative doesn’t appeal you as much now. It becomes stale. It has just outlived its resourcefulness and stopped simpering at you with the efficacy it once had.

That’s when you are most likely to give up on something that could have added impeccable value to your path.

Three things perfection demands that perfectionists feel the need to deliver:

- Time for editing.

- Time for reflection.

- Time for more editing.

The sense of never getting satisfied is what makes you seek new, and often extraneous, mentorship. While it’s good in different contexts, it is misleading when trying to get something produced that is focused on a specific discipline.

The standards of perfection are often found on shifting grounds that change with how frequently you relate to your experiences with better standpoints you come to emulate every new day. When no two standpoints could ideally be the same, nor can the measure they impact on the skill, thought-basis and the quality of a project be viewed from the same perspective.

The minds of perfectionists give room only to so many changes consistent with the kind of determination they have that it’s not going to be long before it takes for a paralyzing flick to surface. Everything collapses in a snap. They have come so far down the path sweeping along the way, making sure to produce impeccable quality, only to find the path impure again.

To quote from an article on Perfectionism featured in Psychology Today, “What makes perfectionism so toxic is that while those in its grip desire success, they are most focused on avoiding failure, so theirs is a negative orientation… Perfection, of course, is an abstraction, an impossibility in reality…”

There are several ways you could take to having a solid path around the confines of obsessive perfection. Here are four:

- Barf now, clean later. If perfection becomes so much of an obsessive practice, a lot of resources and a ton of editing can go to the smallest parts. Just get it all out, relieve yourself of the expectations, and start again on the same project with space to learn, adapt, and improvise.

- Get your “shitty first draft” done. Mediocrity is the one thing that does not differentiate your activities as of an activist. That’s why you are not going to squeeze the most out of the first draft, but take the best out of your third draft. After all, Mark Twain has said, “The time to begin writing an article is when you have finished it to your satisfaction.”

- The more, the merrier. If you take someone from your discipline who has still not gone viral, but single-mindedly determined, you are going to find his process governed only by the simple practice of doing as much of what he can in what he’s an expert at. And he’s going to go viral sometime, if not by principle, but by the mere statistical possibility of the enormity of his portfolio. The more you put in the field, the better the chances of you being desired by the “Law of Averages” for your creative breakthroughs to happen.

- “Blocks” are only excuses. It’s normal, as a perfectionist, to experience writer’s blocks (or more precisely, “Perfectionist’s block”) because you couldn’t find the best yet. Such “blocks” are only excuses to justify holding yourself at a lower ground than what you are capable of; to justify disentangling from the commitment and passion you claim to have resonated with your soul, because you don’t want to startle your best by abrupt force. Well, before 1947, writers didn’t know Writer’s Block was a condition they could actually have. If you didn’t learn about it, you wouldn’t think about it long enough to diagnose yourself with the “excuse”. It’s all in your mind.

Your best work is not what you spent the most time on, or what suffered through the majority of your skepticism and scrutiny. But what produced the most part of your growth along the way of getting there.

Take the Compulsion out of Your Purposeless Routines

Now let’s say I wake up exactly at five-thirty in the morning every day. It’s not something I make myself do regardless of my preferences. It’s exactly when I want to see the world break dawn.

There are two kinds of routines:

- Those that were formed for you

- Those that you formed

I don’t compel myself to wake up early in the morning. I just can’t help it. This routine was formed for me possibly before I had been able to draft my preferences. It’s not going to be in a checklist, but still is more a part of me than other stuff I’d want to go according to my preferences. The same as catching the bus to college at 7.45 sharp in the morning. The same as eating my breakfast ten minutes prior to that.

Probably, we don’t get to have a say about the routines that were formed for us.

But watching TV an hour straight after dinner is one of the many rituals you may be pushing time for amidst other obligations. This is a routine that you formed, and it’s compulsive in most cases. In his book “East of Eden”, the Nobel-prize winning American author, John Steinbeck, says:

“It’s a hard thing to leave any deeply routine life, even if you hate it.”

Some of these routines could make you believe they were for your personal development. Order and organization make you look so good they don’t let you realize you revel in the same level of your potential and wisdom. Most part of your skills remains untapped when you aren’t being subjected to what would require at least their optimal usage.

If there’s one thing substantially beneficial in following a perfunctory routine, it’s that it makes you perfect in your everyday things and makes you believe you have achieved success. Maybe the structure is infallible. The dots there are already connected and it requires of you only to traverse along the line.

But that’s why, the best thing about a routine often makes it the least supportive of growth. A life without challenges is submissive to a level two on a scale of one to ten of growth. For most people, the level two is too comfortable to snap out of and tweak for creative changes.

Routine then becomes a routine to follow, and it’s harder to change twice to be able to get into the craft.

But are your routines purpose-driven?

Do they have a direction?

Are they going to culminate in your success or only about to go on an infinite loop?

If you kept it going for the rest of your life like you did today, would you achieve your goal?

You lose your significant purposes to a every day “softening” of the rich complexes of your potential. Hence, your goals are stranded, and the longer it gets with practicing in a comfort zone, the shorter it takes to accept it over a pursuit of hardship.

In his article, “You Can Achieve Anything As Long As These Conditions Exist”, Thomas Oppong says:

“Your body and mind crave easy routines but real growth and success happen outside your safety bubble.”

You have to create a purpose and work towards it. Routine does not give you a purpose or make you want to find one.

You don’t know what you are missing when your thoughts are boxed inside compulsive habits. Compulsion tends to underwhelm the creative output if it’s not channeled purposefully. The complexity of your psychological outlook then streamlines to deliver uncertainty to your own principles and decisions. It makes simple things appear better, and important things appear simpler.

The decision for your creative startup might be a good thing. But the concrete of your routine tries to keep itself intact by pushing uncalled productivity out of its schedules. In his book, “Den of Shadows”, Christopher Byford says:

“Disillusioned, people simply carried out their work as intended, drinking away sobriety at the end of each hard shift and repeating the process until death.”

Every single thing of what you’d so far practised all your life tries to repel abrupt changes. You feel responsible to hold yourself to that.

When you sink deeply in an environment where everything’s an assembly line requiring of you to tend at regular intervals, and where there’s comfort and convenience, and no space for anxiety and depression, nothing seems to be a problem of any sort. You may not match it with your lack of progress. Maybe you are ready to put in extra hours, stay late, or do the “lark” routine — that, however, you should know will produce something of far less quality than you intended because of the absence of centred devotion.

How much of yourself have you so far sacrificed to mismanagement of time?

We all have at least one good opportunity we had invented excuses for to not indulge because it either conflicted with the order of a well-drafted schedule or gave this feeling we couldn’t get it done without the dedicated preparation we wouldn’t get ourselves used to with so many other matters at hand.

When same goals are lived in a routine, growth is stunted.

You can see your ulterior goals for the future, and yourself having attained them, but you live without the right preparation.

“Change” is not a phase, nor a part of life you will have to cross sometime. Change is a choice. Particularly when bound by the obligations of a routine, it could sound like an invasion. If you don’t embrace it when you have to, you might forever be stuck with the loop.

Dan Cumberland from The Meaning Movement says, “One of the great parts of having a routine is being able to break your routine.”

If you couldn’t break your routine when it most requires for it to be broken, this is probably why:

- More often than not, you make irresistible obligations out of your routines than for what they actually are.

- You are afraid of the commitment of change that you will have to live up to.

- After having been left with illusions of contentment found in the uneventfulness of routine, change has become unnecessary.

- You mistake all works of routine to impact a cumulative effect on your life. Well, except the ones that do, most don’t.

Writing a thousand words every day can bring cumulative advantages on your life some intense practicing of the habit after. But it takes time and radical focus, that to fit the commitment alongside other matters requiring as much exertion would be a total disaster.

Sometimes routine can have your productivity waiting out days on end, even years. It gives reasons to believe you are occupied enough to not care about things that actually matter. Having other compulsive works means you already believe you are going to save starting your project for when your mind is absolutely free, and make the most out of it then.

A few steps to follow to circumvent all your purposeless routines:

- Understand routine doesn’t help you grow. You can feel like you are successful almost every day if you had set your daily rituals far from requiring the use of your fullest potentials. You will be successful, but you won’t grow.

- Follow the “Alexander’s technique” of absolute mindfulness. Although Alexander’s technique is primarily used for treating certain flaws in the skillful practices of an artist by including mindfulness in whatever he/she does, it could also be used to reach any goal set by the mind. It involves being in complete awareness of your world, and understanding what you have to change in yourself. It includes turning the “autopilot” off and taking things into your own hands.

- Break the obsession to want to follow a perfect order. Order calls for a line to be drawn and that line be maintained straight. It makes you want the same things done the same way. Order breeds the fear of imperfection. And perfection breeds procrastination.

- If you didn’t think you couldn’t get your strewn thoughts focussed on a major change to keep you defined exclusively, you were probably working towards becoming someone you are not today. Stave off anything that you could do any other day. Learn to prioritize.

Warren Buffett probably has it better about the compulsiveness of a routine than anybody else:

“Chains of habit are too light to be felt until they are too heavy to be broken.”

Remember that you have chosen this path, chosen to be creative because you didn’t find anything else that appeals you in your normal, ritualistic life, except for maybe the compulsion that makes you think you did. Remove the compulsion and you are free.

Saving the Best for Last Isn’t the Best Strategy

A singular, focused conception of the path you mean to forge in reality, and unwavering adherence to its priorities could be two things you can always count on to give the best of yourself for.

If half the trouble comes from understanding what you are really good at — as opposed to what others say about you — the other half goes to standing up with it.

The best way to communicate with the world is not by words, but by establishing a distinct skill-set. Because when words could manifest ideas, skills bring them alive.

But showing you have skills is the easiest part — as opposed to dealing damage with it:

Because it isn’t as easy to show what you can do with the skills, and what you are generally capable of, if you can’t change your environment and those around you to favorably suit your likelihood and potential.

Living and adapting, for prolonged periods, amidst sensible mediocrity, like a lion amidst sheep, reduces all acts of skilful expression merely outlandish and contradictory. You lower yourself to what’s more commonplace to blend in with your companions. You hope to save your skills for where it would actually matter, and decide to stay dormant until you get there.

Very few people realize and relate to stories of success that for every major feat, there preceded considerable levels of patience through victories that didn’t dent the slightest change.

And the only solution is to engage or create several opportunities and not care about the results, nor the foolish insecurity of running out of your resources.

I had an artist friend back in high school who thought his skills weren’t given as much appreciation as they deserved. His problem wasn’t creating what he thought to be masterpieces (which they were, for the most part). It was taking them up to where it mattered. He always had an excuse for not doing it, however hard I tried explaining to him he should find his skills the exposure they deserved.

Maybe he believed he had to wait until a supreme opportunity was presented to him that would spontaneously break all barriers of exposure and virality, and bring him an overnight success.

Perhaps he would never find his skills home, never participate where his skills can be tested, never be acknowledged. If he didn’t start by making a small ripple, he would never know if he even deserved appreciation. The only appreciation he would forever find would be from me, and he might end up worrying for the rest of his life he isn’t ready for the world yet.

Well then, that’d be one thing he could be right about. He isn’t.

You may think you have to save your best for later, for when you have attained a greater position. But you fail to understand it’s only by giving your best you can ever get there.

It does feel good to live in the uneventful seclusion of believing you have skills someone would come around to dearly acknowledge. That you can stand out amidst all the noise by singing a lullaby.

But think, what record do you have to show for your skills that others might find?

Have you at least tried and failed once?

If you didn’t, you better. Failure is never the end. Failure is a platform you could use to start the work you didn’t get to finish the last time, but now with the furnished knowledge of the one way you can never get it done.

You shouldn’t be subjective to the world around you. You should be proactive. If you were proactive, you would be more insightful. If you were someone with much insight, you would understand giving your best at all possible times would only make better thoughts and ideas to constantly take their places.

All you have to do is believe you wouldn’t run dry sometime after you begin to create. It is impossible for your brain to not come up with something. That’s the way we all are wired. But it is possible for your brain to trick you into believing there is a little bit of planning left, ideals to be upheld before you can make the first move. It’s that bubble you have to break out of.

It doesn’t require a lot to show what you are capable of if you could be straight about how close to or distanced your skills are from perfection for them to be taken to the greater audience. It doesn’t matter who you stand with, how far behind you are from others.

All that matters is you stand.

Indecision Shouldn’t Bother Your Long Term Goals

Whenever you feel productive, and allow the ensuing urge to have your part to the world — or to your society — known and acknowledged, you are inevitably met with two perspectives of thought.

By one thought, with or without your acknowledgement of it being there, you are pecked optimistically, filled with positivity, and at times, even coaxed out of bed.

By another thought, you feel you’d be better off with what you have than see through the possibility of what you can contrive with your expertise go badly beaten by the public eye, or die immaturely.

Success is so enticing you often forget the meaning of creating. You base your visions predominantly on their predicted success rates. You cradle them on their “chances” in the world than for what they actually mean to you.

That could leave you wondering if you should still do it.

If you are a creator and know what you are creative at, you have three things — and only three — to do:

- Get to know your trade.

- Pitch your idea.

- Wait for it to hit something big — or small.

Not the other way around. The journey is what makes you strong. Looking at the results before starting on the process keeps you wondering about the mountainous work involved, that usually precedes indecision and quitting.

There should be lots of instances when you couldn’t decide between doing something productive and heeding the fear you would fail in it. Particularly when the fear that is keeping you away from developing your creative ideas is society-driven, and you hold a key position and it does matter what the society thinks about you, the other end of your indecision becomes pretty strong in the argument.

You know what you must do?

You should think, think, think, and then commit yourself to your ideal in a way you couldn’t back out of it even if you wanted to. And then try and live up to the commitment.

It’s better to make a hard decision now and have yourself fulfilled later on in life than to find the easy way out only to come back again to ponder where everything had gone wrong.

An important thing is that, when it comes to undertaking preparations to attain life goals, you aren’t torn between a sea of choices. It’s either one way where you get to get things done or the other way where you don’t.

When you have doubts arriving at a decision, decide to do what you have always wanted to do. Because if you don’t, you are going to come back to it some point in life, and think about what could have been. And you will hate yourself for it.

The indispensable first step to getting the things you want out of life is this: decide what you want.

— Ben Stein

Oftentimes, the energy and emotions you spend for the anxiety of indecision can rather be elasticized to spending for the actual process. Sometimes even with resources left enough for the “one step back” several times along your path.

The biggest decision you have to make is to know what you want to do. Not if you should do it.

What you should instead be conscious about is these three simple steps:

- Get to know your trade.

- Pitch your idea.

- Wait for it to hit something big — or small.

The Icebreaker

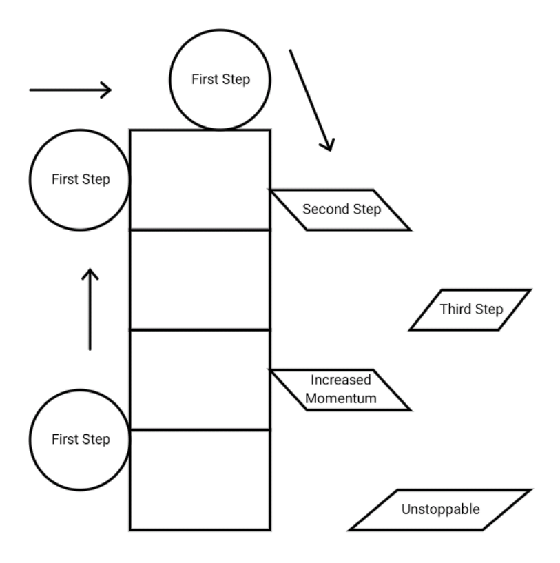

The only thing that’s between you and your project is your starting it. You have to make the first step even if you feel like you have to give it more time for it to be born perfect. Based on whatever disheartening obstacle — on whichever platform you intend to make your dent — that you might end up believing you have to withdraw your stern ambitions from the path of your goals, after you make the first move, you can hardly stop.

You may have all the reasons in the world — least of all your own muse doubling over for various reasons — to discourage you from making the first step. But that’s only until you make it.

Because after the first step, you gain momentum, and can’t risk losing it.

After the first step, the second step looks inevitable. You have built the required momentum to upscale. Now the third step is inevitable. And you use the renewed momentum for the next step.

The first step, if something, is definitely an icebreaker.

Because you are as awkward with what you want to create as you are with the girl standing at the end of the bar. She is making you feel like she’s shooting wayward glances at you, yet so alluring that she also makes it clear she would destroy you if you tried to talk to her.

The first step puts you in touch with your muse, makes you understand it will get better with time.

What you have always been sure you can never accomplish has at least a few simple first steps that you can do. By basing your standards and efficiency on the simple things that will one day compound to give your results, the process is made tactically easier. Trying to attain the greater glory is only made easier by having even a little of the process already under your belt to work your way up to where it would require increased bits of smaller victories — as opposed to a mountainous proportion of a single victory.

The more time you spend not beginning your work, the more chance of it taking asylum in a wonderland, the beauty of which you would now hesitate more to “spoil”. The writing of a book is at the perfect centre of your wanting it to be immensely perfect, and your wanting it to be written. While the latter extreme is heartening, you will find the former extreme often pinned to your own tail.

Don’t fret about where you would rather have been, and fail to make the most of where you are. Let that novel that’s been suffering to come out actually see the light of a screen. Don’t worry about it dying immaturely. What little you add to it each day is an inspiration to start from the next day.

When you make the first step, you begin to see beyond your blind-spots where you believe you have to get it done somehow, because it’s that, generally, something simple as a commitment seals your “point of no return” often irrevocably.

But if you have yourself believing you have had it all worked out long ago, and are only waiting for the “opportune moment” for it to come out, you probably will never see it.

Because the opportune moment is now.

Right now.

Rise “with” Your Creative Flow

For a creative with negative anticipation, not knowing when he is the best with his mental clarity, and not being able to discern which part of his illusive systems take to outsourcing significant gains to all such behavior and negativity could set in motion an “independent” Domino Effect. An effect he should have set in motion himself.

And the Domino Effect will not be of him, but of his potential; small dominos hitting bigger dominos each time, unlocking a ripple.

The collective momentum of each domino of his potential would lock rightfully in place to unveil a quadrupled advantage: his potential has grown because of the various changes he’d undertaken subconsciously since the last time he’d put his skills to good use.

And the worst thing of it all? He’s not aware of it. He’s not aware of his monstrous potential because he’s too busy contemplating his anticipation, and when could be the best time for him to begin his work, while in fact it’s right now, but he doesn’t care to notice.

One of the most important things in making the best of your skills is to find your flow. When you do, great things begin to happen. You don’t force your thoughts out of you, they have already paved a path to come effortlessly, and only require you to want them to come out.

But finding your flow could prove hard enough. You may have let your dominos pass, and at a later time, try to rise to your potential instead of rising with it.

Famous writers have agreed their creative potential is enhanced during particular times of the day every day. Stephen King advises to write at the same time every day, and not stop until your thousand or so words are over. This could help set up a mutual understanding between you and your muse about when you will show up as a routine, and for your muse to make itself available at the time.

You have to be detailed about what works for you, and be able to connect the best of you and the best of your physical and mental environments.

When you do this, ideas so steep in nature find a plausible way to express in you. The Absolute Threshold (the lowest level of stimulus an organism could detect) of your mentality towards grasping complexities and understanding ideas decreases, which is how you could double the rate of your progress.

When you become conscious of your flow and work with it, you do not let the Domino Effect of your potential happen independently, but you set it in motion.

Conclusion

Bringing an idea alive goes a long way from believing it would take us far someday. Because it wouldn’t.

Todd Brison says, “An idea in the real world looks infinitely less sexy than it does in your perfect brain,” in his article “How to Convert an Idea into Reality”.

No matter how meticulous your research, how great your point, how true your words, how diligent your work, the world will take a long time to care about you. People will always miss your point until they particularly feel they shouldn’t.

Because they don’t want to hear advice from someone they didn’t know existed.

Write without pay until somebody offers to pay. — Mark Twain

So that’s what you must do. Get yourself known first before you can hope to get credited.

Find the hardest path. Keep doing what you are good at every day. Don’t worry if you make mistakes. You can only get better. Eventually, people will come to know about you, because you have been around for some time barking at deaf ears. They will bat an eye.

But you can’t do all this if you get worried every time you get close to your breakthrough about how your work would look on camera. Or how your “other life” — life you didn’t want — would throw a couple of tantrums from to time to make you jump back. Or how you often find yourself wedged between both lives dying to know where things could work out for you the best, but couldn’t.

If you can, for once in your life, bring about a change in yourself, traverse along a path you don’t know the end of, draft strategies others might criticize, and come up with ideas others might discard as foolish, just because it feels good, you are probably on the path to fulfilling your dreams.

If you have a thousand miles to cross, start by trying the first mile than not start at all.

It is indeed an inevitability to look up at something proving immovable to your skills and not know how you are going to do it. Because you might think it’s the same to have to walk 999 miles as to have 1000, and you might be right.

But that one mile, the first, defines you. It defines you in a way that you’ll get to know yourself as someone refusing to quit when other creative people around you have abandoned their passions for what is easy and uneventful. It defines you in a way that you will not be able to hold yourself to inactivity after. Because the first step is always the hardest to make.

Commit yourself to a process, and give all your resources to get it done. Even if it isn’t perfect at first.

Just don’t let a mile tell the difference between who you are and who you are supposed to have become.

References

- Want to be a Creative Genius? Your Goal Should be Progress, Not Perfection by Thomas Oppong

- How Perfectionism Is Destroying Your Productivity by Darius Foroux

- “Perfectionism” — Psychology Today

- You Can Achieve Anything As Long As These Conditions Exist by Thomas Oppong

- How to Break your Routine and Why it Matters by Dan Cumberland from The Meaning Movement

- How to Convert an Idea into Reality by Todd Brison