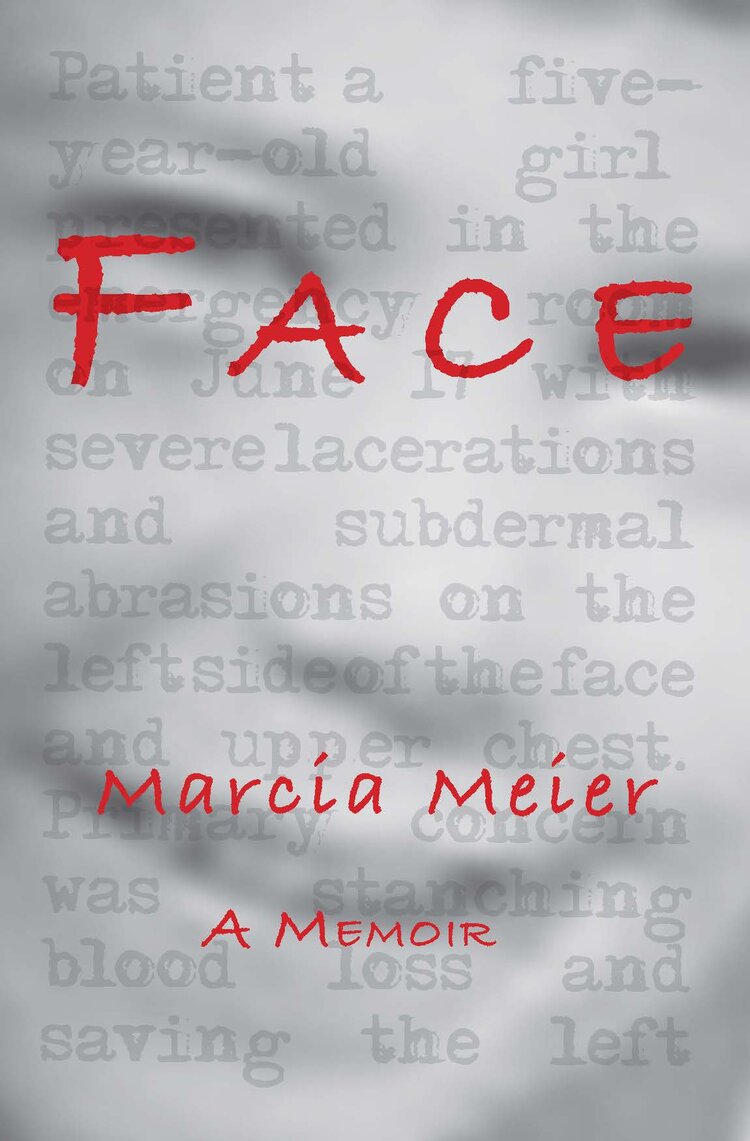

(This is an excerpt from Face, a Memoir, by Marcia Meier, out today from Saddle Road Press. Marcia was hit by a car at the age of 5 and dragged under the car for 200 feet. She lost her left cheek and eyelid and underwent 20 surgeries over the next 15 years. Face is the story of how she survived and came to terms with the complex trauma she experienced. Marcia will be reading from her book tonight, January 12, with Collected Works Books of Santa Fe, 6 p.m. Mountain time. To join the Zoom event, click here.)

I had a brand-new bike, cherry red with chrome fenders: my first two-wheeler. Did my dad teach me to ride it? Did he run along beside me as I pedaled, holding the back of the seat until I found my balance, tipping from one side to the other, then finally discovering that middle place where you know you’ll never fear tipping again? I don’t remember. But I know it was a Saturday, the first day of summer vacation, because after breakfast my older sister went around the corner to her friend’s house instead of to school.

The heat and humidity of a Michigan summer already gripped the day. As I went out to the garage to get my bike, I could feel my blue t-shirt grow damp and cling to my back and stomach. When summer takes hold in Michigan, moisture settles near the ground, sucking everything down with it. By late afternoon, people would be sitting immobile behind screened porches, praying for the whisper of a breeze.

Mom had shooed my brother and older sister and me out after breakfast. We lived in downtown Muskegon, where neighborhoods were arranged in blocks of small clapboard or brick-faced houses, with alleys that bisected each block. The narrow streets were lined with tall maples and oaks, which scattered acorns and, when the temperatures dipped, dropped leaves like graceful magenta and citrine flags signaling the coming winter.

Our neighborhood was filled with kids, and it was never long before a dozen or more would gather. Soon there’d be a game – hide and seek, hop scotch, tag – it didn’t matter. We’d play for hours, coming home only for meals. Adults didn’t worry.

My new bike had a white basket on the front handlebars and red streamers that fell from the handgrips. I had finally mastered riding on my own and was anxious to show off for my friend, Annie, who lived across the street. But on the way, I ran into Mrs. Medema, who was sweeping the sidewalk in front of her apartment building next door.

“What a beautiful bike, Marcia,” she said. “And a two-wheeler! I noticed your dad was helping you balance on it. When did you take off the training wheels?”

“Yesterday!” I said, and smiled proudly. “I can ride all by myself now.”

“Well, that calls for a celebration. Want to come up for some cookies and tea?”

I liked Mrs. Medema. A widow, she often babysat for us. She always wore a dress under an apron, stockings and thick black shoes. Her gray hair was cut short and curled. Three other widows lived in the brick building, but only Mrs. Medema paid any mind to us kids. She lived on the second floor, and her apartment was cozy and bright with sunshine. I parked my bike on the sidewalk in front of her steps and carefully set the kickstand. Then I walked up the narrow stairs with her, holding her hand.

The smell of freshly baked peanut butter cookies filled the apartment. My mouth watered as she took a blue-and-white ceramic plate from the cupboard and put four warm cookies on it – two for me and two for her. She reached for her blue bone china teapot above the stove, poured hot water from the kettle into it and filled a silver tea cylinder with loose Earl Grey leaves. “We’ll let it steep for just a minute,” she said. “Let’s go sit at the table.”

She carried the teapot and the plate of cookies over to a small table near the window, then turned back to get two cups and saucers that matched the cookie plate. She placed one cloth napkin beside each cup, and poured the tea.

“Is your mom busy this morning?” she asked.

“I think so,” I said, lisping. I had lost my two front teeth just a few weeks earlier. “Molly is crawling all over the place. And Chuckie keeps trying to steal my toys.”

She laughed.

“Your dad at work?”

I nodded and bit into one of the cookies. My dad, my grandfather and two of my uncles owned Meier Cleaners. Dad worked every day but Sunday, when we walked four blocks to St. Joseph’s for Mass and saw my grandparents and most of my aunts and uncles and cousins. After Mass the families lingered in front of the stone-faced church, catching up on the week and exchanging the latest gossip. The monsignor, Father Stratz, wandered through the crowd in his colorful vestments. I didn’t like Father Stratz. Short and squat, he had a full head of gray hair, a thick German accent, and though he nodded and smiled at the adults, he scowled at the kids.

A slight breeze came through Mrs. Medema’s screen as I bit into a cookie. I could see my friend’s house across the street, and then I saw her in the front yard.

I took a sip of the tea and ate the second cookie quickly.

“Thanks, Mrs. Medema,” I said through the gap in my teeth. “I have to go now.”

I ran down the stairs, grabbed the handlebars of my bike and pushed up the kickstand with my toe.

At the corner, I carefully looked for cars before crossing. I started into the intersection, where there was a four-way stop. A man and woman in a tan sedan had stopped at the corner. I was halfway across the street when the car began to drive forward. I was so startled I stopped and watched. I didn’t understand why he kept coming. I hunched my shoulders and turned my body to fend off the blow.

Roscoe and Muriel Benn were driving down Fourth Street in a rush. Maybe they were distracted; maybe their children and grandchildren were coming that evening to celebrate their grandson’s birthday, and Muriel was anxious to get home to clean and prepare.

As they approached the stop sign at Fourth and Mason, perhaps Muriel was fussing. “Can you go a little faster, Roscoe? I still have to make the cake and get the roast ready to go into the oven. You’ll have to help with the potatoes. This darn arthritis. I can’t work the peeler anymore.”

Roscoe pulled to a halt at the stop sign and then drove through the intersection. There was a strange scraping sound. People on the sidewalk were yelling at them. What were they saying? Muriel rolled down the window. “Stop,” they were screaming. “Stop!”

Roscoe braked and the car came to a halt about halfway down the block. People were running toward them, surrounding the car. Muriel didn’t understand what had happened.

“You’ve hit a child!” they yelled.

As Muriel and Roscoe approached the stop sign, my ten-year-old sister, Cherie, was walking home from her friend’s house. Just as she turned the corner toward our house, she noticed a car driving slowly, and heard a distinct scraping noise, as if something were being dragged underneath. People on the sidewalk started to scream, “Stop! Stop!” As she watched, Cherie realized my new bike was trapped under the car. When the sedan stopped it was nearly in front of our house.

I had been dragged, caught with my bike under the car, nearly two hundred feet.

Cherie ran to the front of the car and looked underneath. I was lying on the street under the driver’s side. The bike was stuck under the carriage; I was still holding the handlebars. The left side of my face was gone.

Cherie ran into our house. Mom was in the front hallway, talking on the phone with my grandmother, Mimi.

“Marcia’s been hit by a car!” Cherie screamed. Mom dropped the phone and ran out to the street. My sister picked up the phone and shouted, “Marcia’s been hit by a car and she’s dead!” She hung up the phone and ran after Mom.

Mom’s morning had begun early. Dad was gone by 6:30. Mom woke three-year-old Chuckie and baby Molly. She helped Chuckie get dressed and brush his teeth. She got a bottle for Molly, and cereal for Chuck. With four children and two adults in the house, Dad often said our cramped kitchen seemed like Grand Central Station. A large chrome table with a yellow marbled linoleum top crowded one corner, surrounded by five chrome chairs with padded yellow vinyl seats and a highchair. The cupboards were dark, the appliances spare. A small window above the sink, decorated by a frilly white lace curtain, looked out onto the side yard. Once we were all fed, Mom would send us out to play and clean up the kitchen. She was petite, though pudgy around the middle with the remnants of six pregnancies. Her dark-brown hair was clipped short and styled, and her deep-brown eyes were accented with thick, black brows. Mom put Molly down for a morning nap and started some laundry in the basement. The telephone rang. It was my grandma, Mimi, calling to check in, as she did every day. They fell into an easy conversation.

Suddenly, Mom heard people screaming outside. She was about to tell my grandmother to hold on when Cherie burst through the front door.

“Mom, Marcia’s been hit by a car…”

She dropped the phone and ran to the street. As she drew near the car she saw the blood. She saw my bicycle. She felt her chest tighten, and thought, “Not again, not another one….Dear Lord, don’t let it happen again…”

By midmorning, Dad had made his rounds of the dry cleaning plant and stores and was pressing pants in a back room where one of his workers, Carl, was operating the dry cleaning machines. Hot pipes and machinery hissed and moaned. Dad was wearing shirtsleeves, but Carl was wearing a tank top already wet with perspiration. It was insufferably hot, despite the big fans droning and blowing stagnant air from above. The smell of cleaning solvents permeated the plant. When the phone rang, it was Judith, a longtime employee, who brought Dad the news.

“Bob, there’s been an accident,” she said. “It’s Marcia. Go to Mercy. They’re taking her there.”

He dropped the pressed trousers and rushed through the plant, ducking automatically under the pipes and conveyer racks that hung low from the ceiling. His Ford station wagon was parked in the back alley. On the way to the hospital, all he could think was, “Please God, not another baby. Not Marcia.”

What is a face? Eyes. Nose. Mouth. Cheeks. Chin. Forehead. An invitation … or a warning. A reflection … or a misrepresentation. The still surface of a deep pool … or a raging creek. Does a face really say anything about a person? Does it say everything? If a face is destroyed, does the person change? If you create a new face, do you create a new life?

When mom got out to the street, the car had been backed away. Someone had lifted the mangled bike off of me and laid it aside. Mom cradled my bleeding head until the ambulance arrived. A neighbor took Cherie and Chuck inside to comfort them and check on Molly. After the ambulance left, Mrs. Medema took her garden hose and washed the blood from the street.

I have tried to imagine my mom in those hours, drenched in my blood, holding vigil with my dad, reeling from the possibility she might lose another child to an unspeakable tragedy.

When our family physician, Dr. William Bond, saw me in the emergency room, he doubted I’d survive. My cheek was scraped off down to the bone, my left eyelid was missing, and the bottom lid was carved away from the eyeball, though the eyeball was intact. There were deep cuts and scrapes on the rest of my face and upper chest. I had lost a lot of blood. Emergency room doctors worked feverishly to stem the bleeding. They inserted intravenous lines into my arms as they tried to keep my heart rate and breathing stable enough to take me into surgery.

One of the three doctors who worked on me was a thirty-nine-year-old plastic surgeon who happened to be at Mercy when I was brought in. Dr. Bond asked him to see me as a personal favor. Dr. Richard Kislov was a brilliant surgeon who immigrated to the United States from Germany. He was known best for re-attaching severed limbs, a particularly handy skill in Western Michigan where automotive factory injuries were common. Dr. Kislov and the other doctors worked for hours, pulling skin together to fill the vast hole that had been my left cheek. They formed a bridge of skin to cover my left eye, sutured the wounds on my chest and bandaged my head. They kept me alive.

There is a place you can go, a dream state where it is easy to imagine that whatever your five senses may be telling you, whatever sounds of oxygen tanks or rustling uniforms, whatever piercings of your skin or peeling of gauze from your torn face, whatever smells of alcohol or ether, they are not real. The only true thing, in that liquid place, is the comfort of the warm encirclement of your dad’s arms, the familiar drone of the box fan in the window down the hall, the slight breeze in the sticky heat, your mom’s voice reassuring and deeply resonant. All reality fades into that place, and holds you suspended and safe.

Was that deep-water suspension induced? Or did the mind take over, protecting by obfuscating, by creating a separate reality? How long did I lie there, blissfully unconscious? Days, weeks – it could have been a heartbeat. But when I awoke, all that amniotic protection evaporated in the harsh whiteness of a hospital room.

I didn’t know where I was. My head and eyes were wrapped in bandages, my hands tied to the sides of the bed. I did not feel any pain, but my head was heavy and I felt woozy. People around me smelled of antiseptic and starched clothing.

I was afraid.

I heard my mom’s voice. She said, “We told you never to cross the street without looking.”

But I did. I looked both ways.

(Face, A Memoir is available from major booksellers like Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop, and can be ordered from any bookstore. Please consider supporting your local independent.)