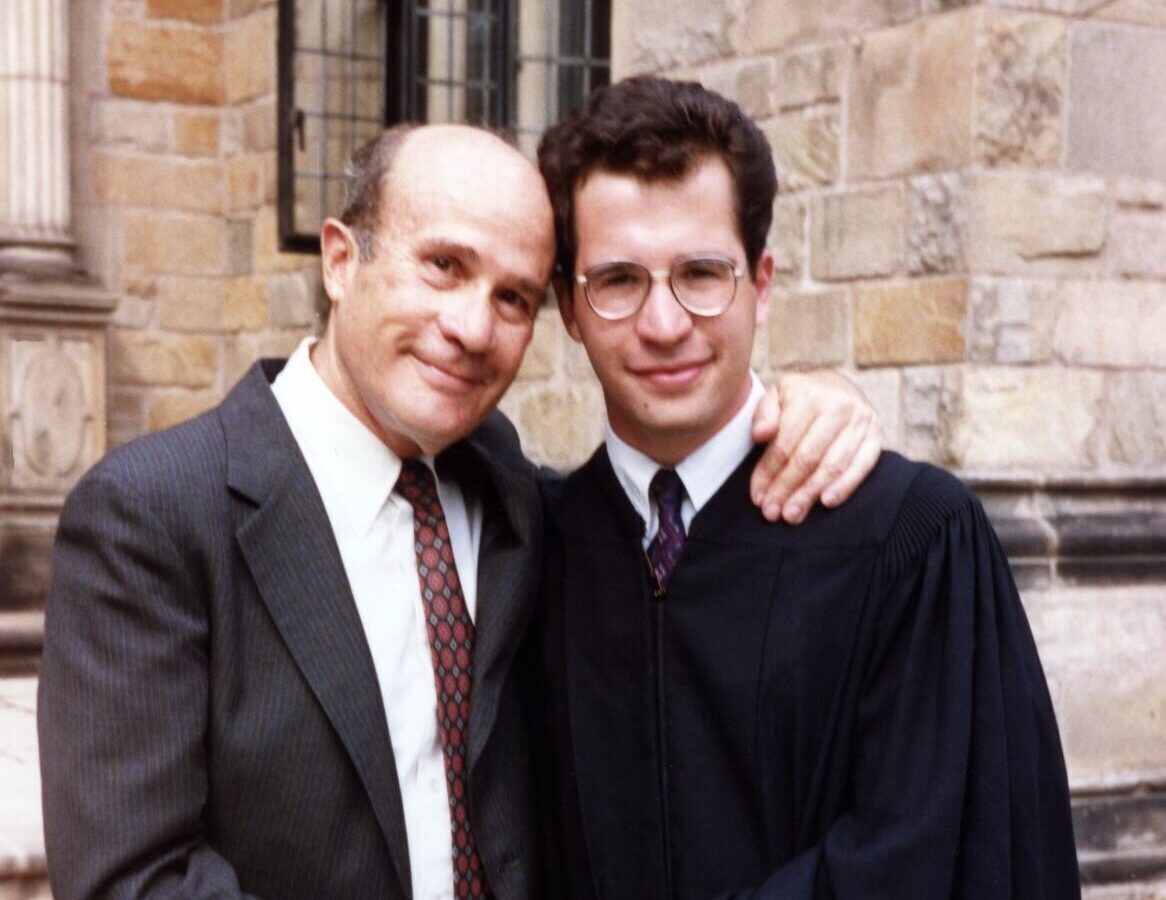

My father passed yesterday, and I have been thinking of the gifts he gave me and what it means to carry the best of his spirit forward, to share with my children, my friends, with you.

My dad grew up as a depression-era Jew emerging from the Coleman clan as his grandfather came here – one story finds his grandfather looking hungrily at a bakery and being noticed from someone from his village in Eastern Europe and offering him food and help. He started a candy store and then a hardware store in Brooklyn, which became Coleman Brothers. My father worked there as a kid sometimes.

Sometimes hints of that time would emerge in my dad when he would tell us about his father drinking tea from a glass and holding a sugar cube in his mouth because it was scarce. We would go to the Second Avenue Deli and my dad would sometimes conjure memories of that time as he sipped tea from a glass.

But other parts of my dad’s history, his soul, were far more hidden from view. He lost his mother to mental illness and this haunted him so but he barely spoke of her. As I grew older, I could see more the tremors of that loss – and how mightily him and my mom worked to provide a home unstained by loss, even though my mom lost her mother young as well. My parents shared a privacy, a reticence.

I only gradually glimpsed the hidden cool of my dad’s college and graduate school life. As I spent my time in college studying, I realized my dad spent much of his time at Cornell playing billiards. In Chicago in med school, he and his friend stole materials to make a clinic for the largely Black community around them that lacked care. I was the dutiful son of a pool shark, a thief who practiced without a license, but also a more irreverent and radical man than I knew. My dad’s efforts earned him a table at the jazz club which is where he met my mom.

My father was a psychoanalyst who practiced in the apartment next door to our home – a door in my parents’ bedroom led to his office – a place drenched with books, the smell of pipe smoke, but bound by an iron wall of secrecy. He would never talk of his patients, and no amount of childhood curiosity could ever have me dare to break the holy sanctity – I trembled even when alone at his office at the thought of opening a drawer.

For me the first sacred space was the intimate conversation – the place where someone shared of their soul was never to be broken, cheapened or shared lightly.

As I grew up and got to know my father’s friends, some of them psychoanalysts, I sensed a distinction between the good analysts and the bad ones. The bad psychoanalyst felt that they had special knowledge which gave them immediate insight into whomever they would meet – they had a code that could quickly reduce someone to a pattern. For my father psychoanalysis was instead an exquisite intensity of listening, of paying attention to each new person and observing.

He was so reserved talking about his work that revelations came sparingly. One night on a bike trip we took together in Normandy he explained to me that he thought his craft was to make people free, to help them to wrestle with themselves, their past in ways that would allow them to make fresh choices. He said to me ruefully he had a patient he didn’t think was a nice person, and he was uncomfortable that he was making him stronger. But my father devoted himself to a healing restraint, and found divinity in gradually seeing deeper, in seeing the hidden connections and walls to dismantle the bonds we weave in ourselves.

That restraint extended to helping me with my homework. He never would give me a damn direct answer but dragged me down a painful path of discovery. When I asked him a question about science, I wanted Google and he gave me the Encyclopedia Brittanica. I have decided to visit this same abuse on my own children and that’s why I bought one of the last printed copies – so they will have to suffer as I did reading around and wasting hours to only gradually discover what they seek.

It was sometimes more painful when this restraint turned to discipline. He never raised a hand against me, and there was a deep gentleness. But sometimes it felt violent when he would turn to me with disappointment and ask me why I had done something. I never feared a blow, but I became acutely conscious of his frown or a shake of his head – the wave of disappointment.

My father is one of the only people in my life with whom my relationship profoundly changed. I was living at home for a brief stint after college and he would greet me each evening often with some failing, something out of place. I had left a dish out, or my sneakers in the living room. He was always especially attentive to anything he saw as a waste of money. He would itemize my phone bills and was especially enraged that I would drop money and leave it lying around. Since I was very forgetful he always had a target. I finally said – Dad, it is a certainty that I will lose some money. The only question is whether I will make more.

But then one night we had a real conversation. I told my dad that I wanted to get to know him better at this stage of life, but that when he began with an observation about something out of place it shut me down. I said that I got lost in that and couldn’t talk to him. And my dad changed. We began to have dinner together and talk of other things. Our relationship and friendship deepened.

As I came to know my father better I sadly glimpsed what I think was his great tragedy, the early loss of his great friends. He was a reserved man but could not shield me from the depth of the blow of the loss of Bob Glaubach and then Don Kaplan. My father was a man of few friends, and he lost titans in his life. I will never forget the eulogy he wrote for Bob Glaubach which he uncharacteristically shared with me. He wrote of Bob as a whale of a man, nonetheless filled with grace.

My father spent a great deal of time in worlds of his own. Even as he dragged you into them, he was really like an Ahab in his own obsessions. His remorseless need to go fishing and biking, dragging us all along. The hours he would spend reclaiming his heritage of the hardware store fixing something. Most hilariously, spending hours hunting for a deal – for yet cheaper clothing. When my father would approach with a smile touching a new vest or piece of clothing – it demanded that you guess how much it cost and no number was too low. He loved listening to classical music loudly and losing himself.

At the same time, he had a hint of sartorial splendor in old suits that never changed. He loved his ancient tweed and seersucker suits – but he maintained them with an ardor that kept them fresh. He was so cheap but sometimes eerily stylish. He refused to improve the apartment – he loved sameness even as our home became rougher around the edges and frozen in amber. He ate the same lunch at the same coffee shop, and our cupboard was filled with a terrifying sameness of tin cans of tuna and salmon.

There were so many inheritances I did not take from my dad. I fix nothing, waste money, and would often prefer to read a book than accept the fluster of fishing, skiing, and even biking.

But then there are the deep gifts. At my best, I listen. I have often thought that If I could listen as my father did and speak as my mother does, I would have all I needed.

My father spent hours looking at a single piece of art. I somehow both hated and loved it when he would put his hand on my shoulder and tell me what he had seen. I remember in Rome he stared for so long at a Caravaggio depicting Mary holding Jesus and two peasants gazing up at her, their feet stained with dirt. Finally, he said, “Do you see the reluctance? Do you see how Mary clutches the child – she does not want to give him up.” My father found in Caravaggio eerie psychological insight, as when he paints Matthew with his head in his hands when called by Jesus.

My father, like my mother, had no interest in pedigree – in the show of education, only the idea – the looking at the specific thing. I remember when he asked me what I thought of Sex, Lies and Videotape – a movie we had just seen. And for so many reasons the halting encounter with sex in that film resonated with me – and when I answered I felt in him the deep pride that his son might witness some of the psychological depth he so sought. He didn’t say much, something like – “that is very interesting,” but I sensed he cared more about that answer in some ways than any other achievement.

My dad was concerned about me being gay. He was afraid for my health. None of this diminished his love, but he was honest even to the point of once telling me that he was concerned about me raising children with a man. He knew something of the cost of the absence of a mother. What was amazing was to watch him change as Patrick entered my life and our love flourished. Because whatever he thought my dad was open to the truth of what he saw, of love and desire. At my wedding when he gave his toast he said he was looking forward to the little ones that would come from our union, and he meant it. He never really got to know Zack and Scarlet because of his dementia, but it means so much to me that they carry his blessing.

I bought my father a beautiful Italian bound book in England so that he would write down his thoughts on psychoanalysis. I thought he saw a different and deeper craft and it needed his defense. And I remember finding that book empty years later. My father’s mind was muted so long by dementia and his loss has been a hard, slow one over many years. At the end, I felt in him the prison walls so acutely that I hoped for his release. Now facing his end, I hope to share some of those unwritten pages, inscribed in me. I will begin by a trip to Amsterdam, alone to look at Vermeer’s paintings for a long time. I know he would have loved to talk about that.