As my friend Tabby puts it, there is a thin, elusive line between acceptance and surrender. I am walking down Chauncy Street, skating that line. It is April 2003, I’m in my second year of law school, and I am using a walking cane for the visually impaired for the first time.

I spent the last two hours with Joe, a “mobility coach.” He taught me cane techniques as we walked Harvard Law School’s campus. Then he urged me to practice these basics as much as possible, to “get comfortable with the cane.” Now I’m walking down Chauncy Street to meet Dorothy, practicing, or trying to, at least.

I do not feel comfortable with the cane. I feel very awkward. With each step, I swing the tip of the cane from one side to the other, just above the sidewalk’s surface, gently tapping the ground at the end of each arc, like a walking metronome. Step-tap, step-tap, the cane sweeps for obstacles one step ahead of me.

That is the theory. In theory, the cane is a simple, elegant, helpful tool. In reality I am a newborn, sloppy cane swinger, and I am making my life much more difficult by stubbornly assaulting the sidewalk with a graphite stick. My sweeps fall out of sync with my steps. The cane tip’s supposed glides above the sidewalk are erratic bounces and drags. The teardrop tip is little help. Every twenty yards or so it slips into a crack in the brick sidewalk and jams. My momentum carries me forward, forcing the putter grip into my gut. I am levered upward by the cane — the handle digs in and up, lifting me off the ground. The putter grip gut stab is frustrating and painful.

There are other frustrations and pains. I am embarrassed to be seen using this cane. It will undoubtedly be perceived by others — consciously or unconsciously — as a sign of weakness and vulnerability. I do not want to be perceived as weak or vulnerable.

I reassure myself: a few hours ago I got along just fine without this cane. I do not need it. This superficial self-defense only leads to more questions, however. If I see well enough to get by, if I didn’t need the cane yesterday, why am I using it today? Am I weaker than others who cope with sight loss?

Am I committing a fraud? I am using a blind man’s cane, but I am not blind, not completely, not yet. I will likely be perceived as blind and aided as a blind person, but I can still see a lot, can get by. What will those who know me think when they see me with this cane? This last question is particularly troubling. It is the question I keep coming back to, again and again.

I am confused. In my confusion there is disappointment. There is resentment. This will take practice, I tell myself. Give it time. Be positive, be optimistic. You will integrate this cane into your life, and it will prove a great benefit. Be patient.

But that is not enough for me. I do not want to integrate this cane into my life. I do not want to need it. Others will find no strength, no confidence, no power in my adapting to blindness. There is no strength in need. Nothing to celebrate in capitulation. They’ll see only blindness, and it will define me in their eyes. I do not want to be defined by disability, defined by this cane. I am not a blind man. I am a man who happens to be going blind.

What is my alternative? Ignore my reality? Fight it? Is it better to be blindly stubborn or blind and practical? Should I thrash forward against the tide until I drown? Would that make me look stronger to others?

This is progress. It may not feel like it, but it is. This is what I need to do for myself. It does not matter what others will think. What I think matters. That is my choice. I need to confront my own thoughts about strength and weakness, acceptance and surrender. This is who I am. This is my life.

My internal pep talk taking effect, I take each step-tap with renewed focus. Rounding the bend in Chauncy Street as I walk toward Garden Street, I can now make out Dorothy ahead of me, standing in front of our apartment complex, awaiting my arrival. It is a sight to celebrate, an oasis of emotional support at the end of a desert trek.

I straighten my posture, tighten up my cane swings and taps, and put a bright smile on my face. She returns the favor. I experience a brief moment of energized optimism, and my pace quickens. Then my teardrop tip catches a crack and I am stopped dead in my tracks, lifted slightly off the ground, a shooting pain radiating from my gut. Dorothy sees it all. Tears fill my eyes. I fold up my new cane.

There is a thin, elusive line between acceptance and surrender, between strength and weakness, between confidence and shame. Its contours are complex, its form faint and ethereal. As I walked down Chauncy Street I sought to find that line, but I never did, not that day.

That day I was distracted by bright, bold lines, tempting in their clarity, straight and sharp. Disability is weakness. Dependence is insecurity. Struggle is embarrassment. Those are the lies we tell one another. Those are the lies we tell ourselves. There is no malice in the telling, only negligence or ignorance. Those lines are easy to see and easy to understand. Those lines are simple. They make sense if you don’t know any better.

I didn’t know any better. It took years for me to forget those lines, to ignore them, to see beyond them. Only then could I begin to discern the true line, to gain confidence, to understand that blindness is not weakness. I accepted my blindness, then embraced it. I learned to find strength in it, even when others saw weakness. Especially when others saw weakness.

Looking back, I am amazed by my simplistic, misguided notions of disability, independence, and strength. I am horrified by them. I see that they made me weak, not my blindness. They could have made me a victim, bitter and resentful.

It can be difficult to find that line. You may have to search deep within yourself. You may have to confront others who insist upon very different lines for you. You may have to master the minute details of the disabilities, flaws, or short-comings you’d rather avoid, master those details, accept them, and embrace them. It can be very difficult.

But to live eyes wide open you must find that line. That line is reality. That line is truth and power, strength and confidence. You must learn to see it. You must choose to see it.

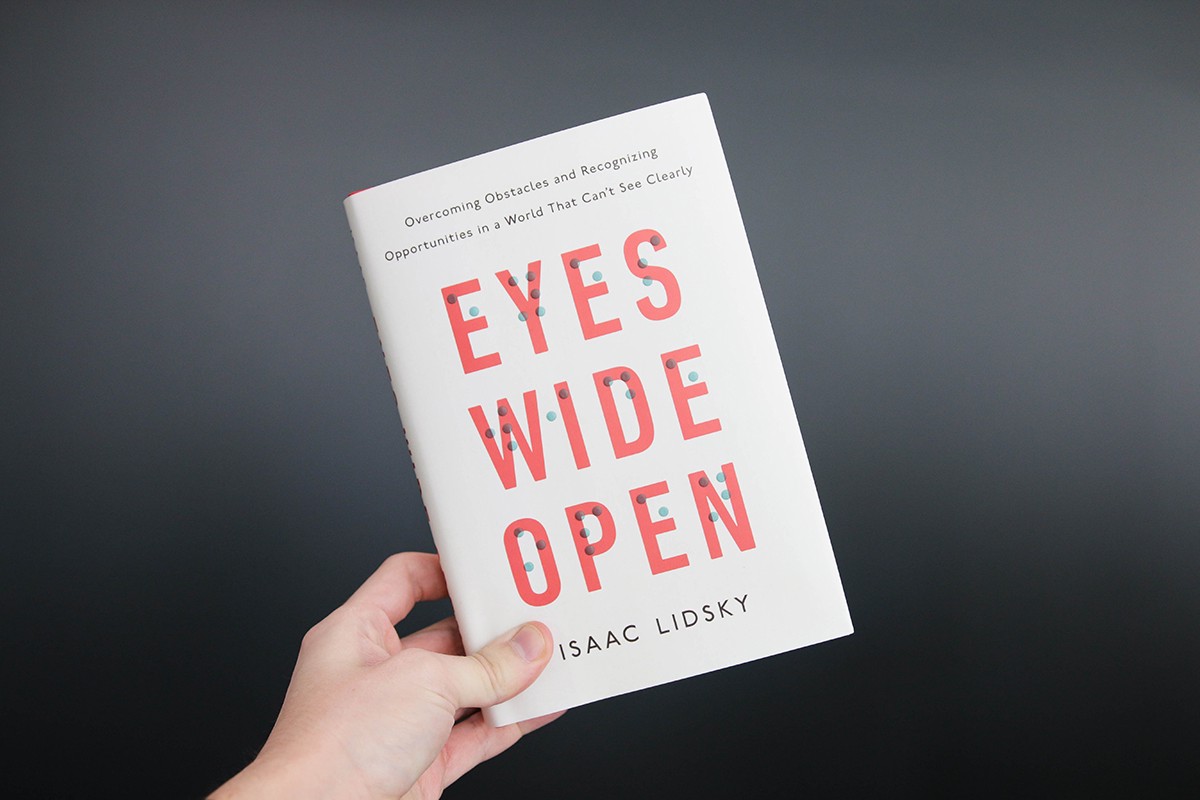

This excerpt is adapted from Isaac Lidsky’s new book, EYES WIDE OPEN: Overcoming Obstacles and Recognizing Opportunities in a World That Can’t See Clearly (TarcherPerigee; Mar. 14, 2017). A former sitcom star, tech entrepreneur and Justice Department litigator, Lidsky is the CEO of ODC Construction, Florida’s largest residential construction services company. A dynamic speaker, his recent main stage TED Talk reached 1 million views in 20 days. A graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law School, he lives in Windermere, Florida with his wife and four children (triplets +1).

Originally published at medium.com