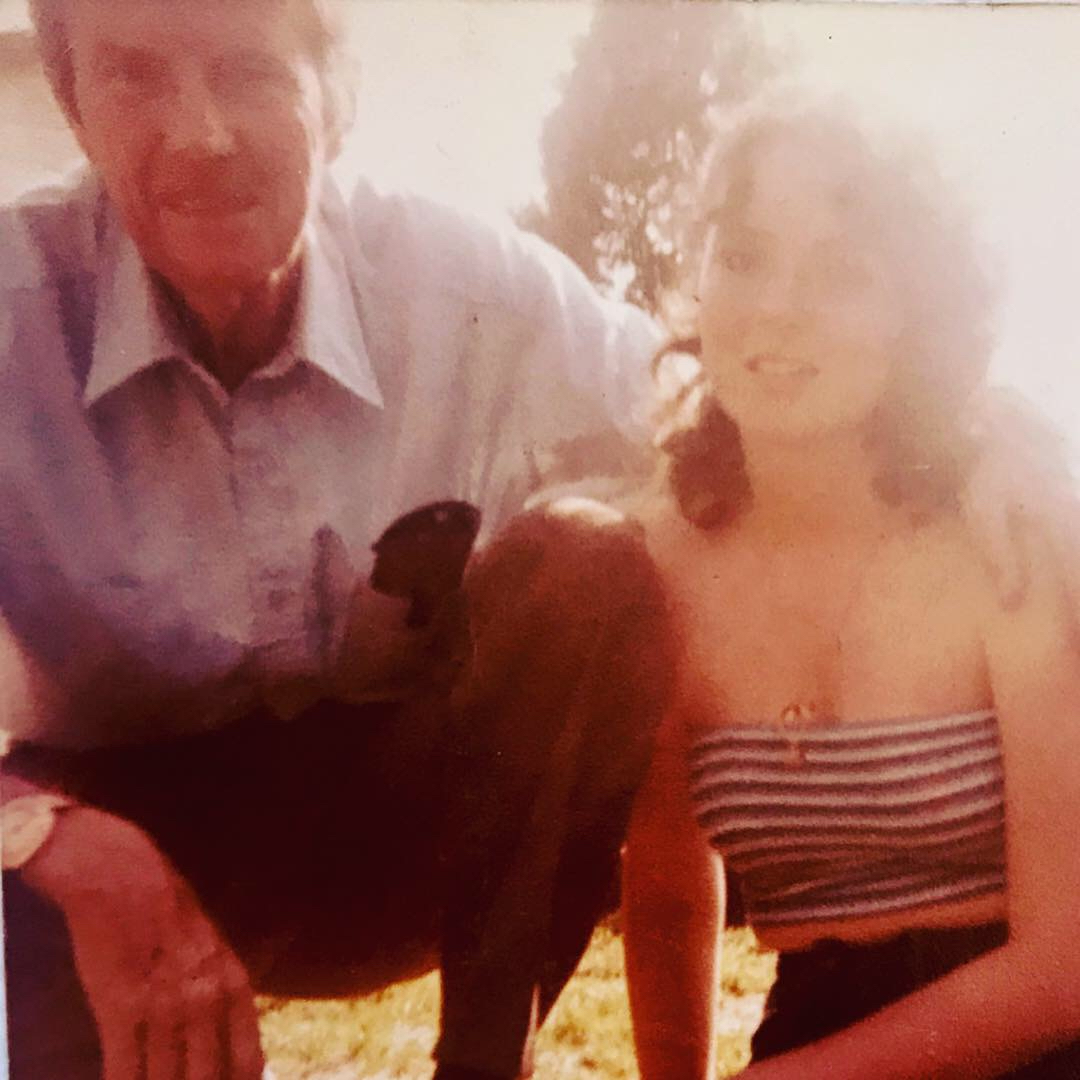

I called him daddy boy. My father, my friend. In fact, until I was 17 years old, he was the closest thing I had to a best friend. He was my safe place, a welcomed lap. The beginning of a verse and end to a joke. He was hammocks and guitar strings and stolen sips of beer. I was his only sunshine, his peachy keen and nagging little helper. I inherited his hazel eyes, his kindness to strangers. Unsolicited hellos bellowed from street corners. He gave me the gift of silly voices and tickles in the neck, awkward burp sounds and singing before breakfast. Strange Dutch-isms and articles before verbs. Because of him I’m good with a wrench and love the smell of wood dust. I have his veiny hands, smile lines and an endless appetite for ice cream. Doing crossword puzzles in pen, enjoying quietude and also, the company of others.

After a delightful meal my father would say I’ve had an elegant sufficiency, any more would be injurious to my flip-flop. Can’t say I inherited that one. My flip-flop only knows the injuriousness of having too much.

He never wanted to make waves. Always happy to wait his turn or give up his seat. If pushed or elbowed or in any way rudely jostled he would never bristle. Nor fret nor fume. He was no victim. He’d probably pray for you, silently ask God to pardon you. He was like that. Ever kind.

When I was five I marveled how he knew that everyone’s name was Mac. He called the bus driver Mac. Would say, Hey Mac, fill ‘er up, to the gas attendant. Said, hey Mac to the coffee shop guy. And each Mac hello’d or smiled in return.

Some of my peers in kindergarten made the mistake of calling him my grandfather. I knew he didn’t look like the other dads. He was 15 years older than my mother. He retired while I was still in grade school and spent the summers watering the vegetables growing alongside our driveway in Queens.

I was his uninvited helper but I just couldn’t contain myself if it snowed and the sidewalk needed clearing. Or if there was a two-by-four being sawed with an end that needed holding. Or if his glasses needed fetching from up the stairs or a bowl of Rocky Road brought down.

I wanted to be his legs, his eyes, his lasting breath. I was obsessed with his death long before he died. I would lay awake and listen for his steady snore and if it stopped, I’d creep into his room and stand over him, watching in the dark for his chest to rise again.

I knew how much I had to lose way before I lost it. The knowing made the everyday that more precious. There wasn’t a stair I wouldn’t climb or a cellar I wouldn’t enter if it meant saving him some steps and possibly keeping him around longer.

But those days came to an end in February, when I was seventeen. I just returned home from my first day back to school after the winter break, in my senior year.

My dad had just come home, looking weak and weary from visiting my battered brother in the hospital. My mom was in the corner, calling my sister with a report. My dad put some soup on the stove to heat up and sat with me at the table. He buttered a piece of white bread and listened to me talk about my classes. He lifted the bread, took a big bite, and that was it. He fell over, dead at 69, of cardiac arrest.

Some may not understand me when I say it was beautiful. It was a lovely way to go and the metaphor isn’t lost on me. Somehow, I knew the way he went — at home, in a house he built, sitting with his youngest daughter, his wife just feet away, surrounded by a life he lived and a family that loved him — was the greatest way to go.

Yes he was only 69, and I, 17. And my mother, 15 years younger, now a widow with me and my brothers to tend to. But the beauty of his passing, without pain or fear or fury, with little disturbance or intervention — just peacefully passing — is why I can think of no better way. Feels awfully intentional, kind and generous. He died how he lived.

Of course I wasn’t done with him. I could’ve used more time, more days, more witnessing of milestones.

I can say he died too early and should have been around to live and grow old — but perhaps what he had was sufficient.

An elegant sufficiency.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.