The impact that the COVID-19 pandemic will have on every facet of our society – the economy, education, the health care system, and our daily routines – is still yet to be fully realized. For many people, these months have involved ongoing escalation of panic, leaving us experiencing unprecedented anxiety, sadness and helplessness.

We can assume that for millions of Americans, the fear of getting sick is a stressful life event already. On top of the risks from the virus itself, the unknown is crippling; how long will this pandemic last and how many of our family and friends will fall ill or die? What will the long-term effects be on our jobs, our housing, and our bank accounts? What will life in our country look like when this is over? We cannot cease to “check on our people” to ensure they’re healthy and safe, but also because many of the emotions and circumstances we are experiencing right now – hopelessness, financial stress, unemployment, housing instability, social isolation – increase a person’s risk for suicide. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors often fluctuate over time, but are exacerbated by difficult life situations. The coronavirus pandemic has us all living in a difficult situation with increased life stressors. It’s easy to imagine crossing over from anxiety to despair and just wanting it to end. Ensuring that someone doesn’t have easy access to a firearm during this crisis could be the difference between life and death.

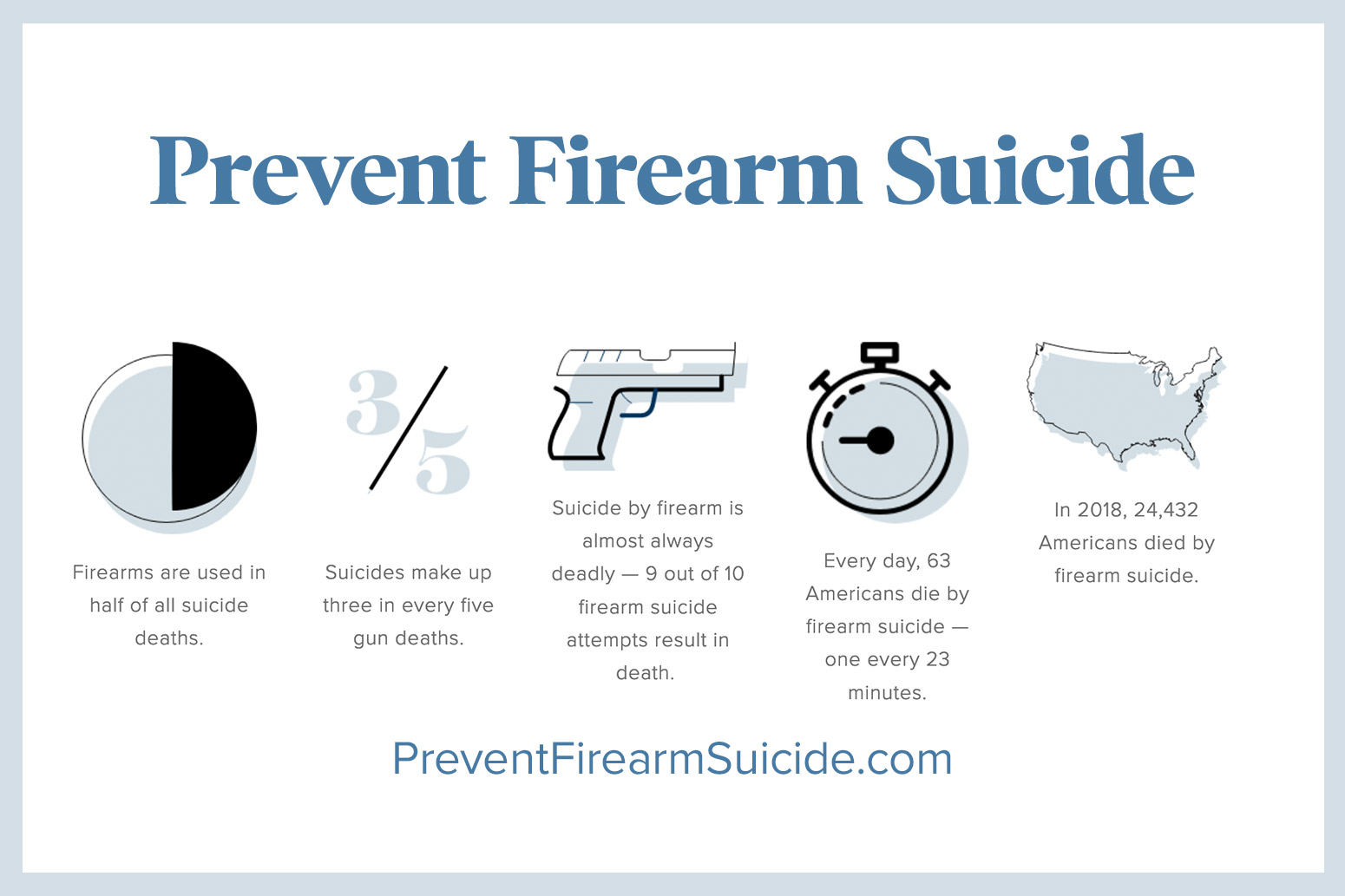

Access to lethal means, particularly firearms, is, in itself, a risk factor for suicide. Having a gun in the home increases the odds of suicide by more than three-fold. While they account for only around six percent of attempts, guns make up more than 60% of suicides in the U.S, largely because they are so lethal. For people with firearms in the home, this moment is a stark reminder to practice safe storage and to talk openly about the importance of said practice with family members.

Suicides in the United States have been increasing steadily over the last 15 years, even before the added stressors brought on by the coronavirus pandemic, the majority being by firearm. While the most recently released CDC data of firearm deaths in the U.S. reveals that firearm homicides are down, suicides by firearm reached a record high of over 24,000 in 2018, the most recent data year available. In 2018, an average of 67 Americans a day died by firearm suicide.

We know that gun deaths disproportionately affect individuals of certain communities, races, ages and zip codes — and it is the people who are already vulnerable to firearm suicide whose risk may increase the most when something as dangerous and panic-inducing as COVID-19 happens. As we continue to face this urgent public health crisis and put prevention at the forefront of our lives, we can also recognize that those most vulnerable to suicide at this time include those living with suicidal thoughts, socioeconomic losses and access to a firearm in the home.

Assuming that more people are experiencing common risk factors for suicide, more people have guns in their homes, and more people are going to be staying home for the foreseeable future, many in our communities are at risk from another public health crisis: firearm suicides.

And while this is not meant to be alarmist, it is a reminder that, as we shift to a new normal in response to COVID-19 we must be particularly attuned to challenges that social distancing and economic hardship will have on our mental health and our households. Ensuring that firearms are properly stored in the home, checking on friends and family regularly, and understanding signs of suicidal behavior are not only suggestions for staying safe in this moment – they’re responsibilities we all have.

Dakota Jablon is the Suicide Prevention Specialist at the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence and Director of Federal Affairs at the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence.

Amy Barnhorst is the Vice Chair at UC Davis Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Director of the BulletPoints Project.