There is a new global movement awakening across the planet. The Fridays For Future (FFF) movement inspired by Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg has brought millions of high school students to the streets this year. The grassroots Extinction Rebellion (XR) founded in the UK last year aims to mobilize non-violent climate action worldwide. And in the United States, Sunrise, a youth-led movement that advocates political action on climate change, teamed up with U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (aka AOC) and effectively changed the conversation by proposing the Green New Deal. With the partial exception of Sunrise, most of these movements and their events have largely been ignored by the U.S. media. More important, hardly any of the reporting explicitly acknowledges these movements as expressions of a larger shift in consciousness globally, in particular among young people.

The emerging wave of youth movements in 2019 differs from the 1968 student movement in a variety of ways. One, the key figures are young women, not young men. Two, they are arguing for a change in consciousness, not just for a change in ideology. Three, they are intentionally collaborating with earlier generations, not just fighting against them. And four, they are using technology in intentional and new ways. In this column, I describe seven “faces” or aspects of this shift in global awareness and the youth-led movement that is taking shape now.

1. The Decline of the Far Right

The recent election of the EU parliament, which is the only directly elected supranational body in the world, was remarkable in a number of ways. In comparison with the 2014 election, voter turnout was up by a significant margin (following a steady drop over the previous two decades), and the widely anticipated success of the far-right parties in Europe was a no-show. All the far-right parties could muster was a 5% increase, from 20% to 25% of the votes. To be sure, 25% is still a lot. But it’s much less than projected in almost every country, including Hungary (where Viktor Orban failed to reach his declared objective of a two-thirds majority), and France (where Marine Le Pen won, but did not exceed a percentage in the low 20s). In Germany the AfD didn’t even manage to surpass 10%, remaining in the single digits in western Germany, though up significantly in the former East Germany — a region that has seen almost 60 years of totalitarian regimes since 1933.

2. The Rise of the Greens in Europe

However, the main story of the EU election revolves around something different: the rise of the Green Party. In Germany, the Greens took almost 21% overall. Among young voters in Germany, the Greens — the only party that clearly positions itself pro climate action, pro immigration, pro social justice, pro EU— are now by far the most popular party. Even among voters under age 60, the Green Party ranks first (but with a smaller margin than among the under-30 voters). Even though the Greens remain weak in Eastern and Southern Europe, they gained strength across the board in Western and Northern Europe (e.g., in France to 13.5%) and in Europe overall.

3. The Collapse of the Center

The other side of this same story is the continuing decline of the center-left and the center-right, the Socialist and the Christian Democratic Parties that have held power both in the EU as a whole and in postwar Western Europe for many decades. Those days are effectively over, not only at the EU level, where this combined block has now lost its majority, but also at the country level in France, Italy, and Germany. In the EU election, the center-right conservatives and center-left socialists were down to 28.9% and 15.8% in Germany and down to a mere 8.5% and 2.5% in France. In Germany, the self-destruction of the center-left may well lead to the end of the government coalition and to new elections within the next 6 months. The next German election, whenever it happens, will for the first time in history see the Green Party competing with the Christian Democrats for the office of Chancellor (current polls show both parties neck and neck).

According to a recent study published by the German government, the percentage of Germans that agree with the statement “The government is doing enough on climate and environmental protection” is down to a mere 3%. The study also shows that people are aware of their own share: only 19% believe that they themselves, as citizens, are doing enough. Furthermore, the study revealed that the most important political themes for Germans in 2019 are not what most people would expect: the top three issues deal with (1) education (69%), (2) social justice (65%), and (3) environment and climate change (64%). In other words: the challenge of learning, the social divide, and the ecological divide. Other issues — jobs, crime, war, and immigration — all ranked much lower on the list.

Why do these numbers matter? They show that, for the past few years, the political discourse in Germany (as in other countries) has been hijacked by the issue of immigration, mainly due to the establishment’s fear of losing votes to the far right. Today, though, citizens rank immigration only seventh in importance. As a consequence, environmental protection and climate change have remained largely unaddressed. Ninety-six percent of Germans want an energy policy that is guided by environmental and climate protection — something the German political class has been incapable of delivering on, due to their unholy alliance with the coal industry.

As the shock waves of the disastrous EU election results for the government coalition in Germany keep rolling in, leading politicians of the losing parties are responding by blaming the young generation, in particular a 26-year-old YouTuber named Rezo. He produced a brilliant 54-minute clip (that hit 14 million views within a few days right before the election) revealing how little the German government has done on the issues that matter most to young people: social justice and climate change.

That’s where German politics currently stands: a government that invented the concept of energy transition in 2010 (which back then was a real accomplishment), but subsequently failed to fully implement it; a young YouTuber who points out the obvious; and then a reaction from the government parties that demonstrates they still don’t get it, shooting the messenger instead of looking in the mirror. Sound familiar? It’s a pattern that we see across countries and that belongs to a deeper “axial shift.”

4. The Axial Shift in Politics

For more than 70 years, the political discourse has been framed by a distinction between left vs. right, between more government vs. more market, between more social justice vs. more entrepreneurial initiative. That’s the old world — the one that is decaying, crumbling, and in some cases collapsing. Being at the center of this axis used to be a recipe for political success in most countries during the 70-year period between 1945 and 2016.

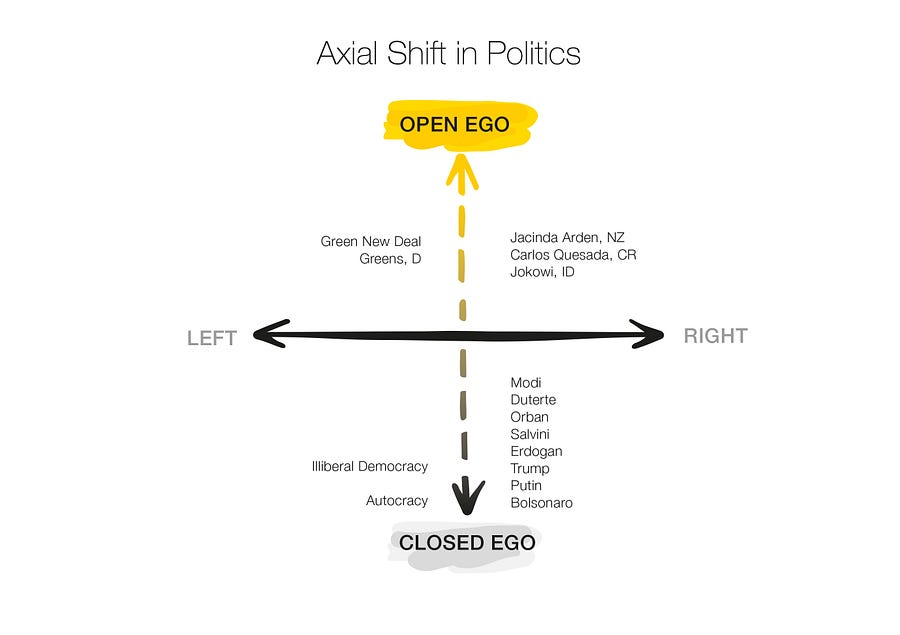

But then came Brexit and Trump. Followed by Bolsonaro, Erdogan, Orban, Salvini, Duterte, Modi, and others who keep reminding us that we are dealing with a much larger pattern. In an earlier column, I suggested looking at this pattern in terms of an axial shift that is reconfiguring our political coordinates from left vs. right to closed vs. open, or ego vs. eco (see figure 1).

Looking at the political landscape through the lens of these new coordinates allows us to spot a few critical things:

· Losing horizontals: The parties that mainly think and act horizontally (left vs. right) are losing; the center is collapsing, but so are the traditional left-wing parties, for instance in Germany and France.

· Winning verticals: Parties operating on the vertical axis are winning: the neo-national populist autocrats at one end of the spectrum, and politicians such as New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern, Costa Rica’s Carlos Quesada, Indonesia’s Jokowi, or the German Greens at the other end.

· From ideology to consciousness: If you are a change-maker on the horizontal spectrum, your main goal is to change the dominant ideology. If you are a change-maker on the vertical spectrum, your main goal is to bring about a shift in consciousness — namely, from ego-system to eco-system awareness. The difference between the lower and the upper half of the figure is a difference in terms of connection (“walls up” vs. “walls down”), reflection (non-reflective vs. self-reflective), and relationship (unilateralism vs. multilateralism).

· Brexit, Trumpism: If your country is trapped on the lower half of the vertical spectrum, you are dealing with a situation for which no silver bullet exists. Instead, you need to engage with a threefold strategy that addresses the major structural reasons for this condition by:

o reinventing the economy to effect sustainable well-being for all;

o reinventing the political process to bring about more direct, distributed, and dialogic modes of participation and conversation;

o reinventing the educational and learning systems to build vertical literacy — that is, the capacity to integrate head, heart, and hand in order to co-shape transformative systems change.

· Role models: If all of the above sounds challenging, that’s because it is. But is it possible? Absolutely. Has it been done before? Yes, and very successfully. Where should one look for role models? To the group of countries that always end up in the global top ten when citizens are asked to rank their well-being or the performance of their educational, health, and governance systems: the Nordic countries of Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark.

· Amplification mechanism: Even though our world encompasses both ends of the vertical spectrum — i.e., Trumpism and ego-system awareness at one end and Fridays For Future (FFF), and Jacinda Ardern’s eco-system awareness on the other — why does most political discourse and public conversation seem to be trapped in the lower half? Because the lower half has some powerful amplification mechanisms in the form of social media platforms such as Facebook, while the upper end of the spectrum does not. Which brings us to the next axial shift.

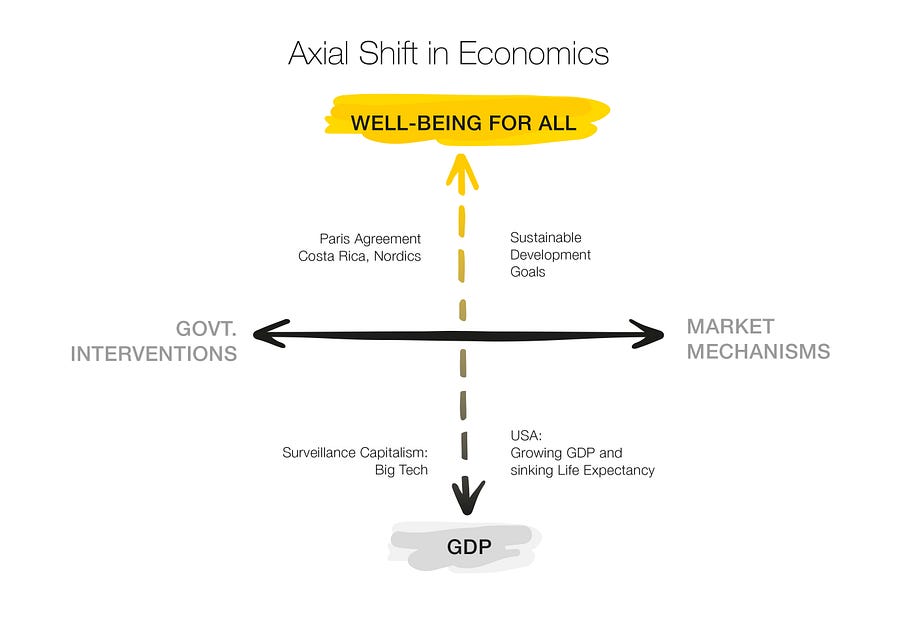

5. The Axial Shift in Our Economy

The second axial shift concerns the coordinates of our economic discourse, which are shifting from the old discourse (about more government vs. more market) toward a new discourse that focuses on the underlying purpose of our economy: more GDP vs. more well-being for all. In the past, most people assumed that a higher GDP would bring more well-being. Today, we know that, for developed countries, this often does not apply. A case in point is the U.S. economy, which has seen solid growth rates for many years in a row, while the life expectancy for U.S. citizens keeps dropping (figure 2). Other examples of economic entities that operate on the lower half of the spectrum include Silicon Valley–based Big Tech firms, such as Facebook. Having made choices in their business model (focusing on maximizing user engagement) that place their own advertising revenues (their “GDP”) above the well-being of their users (“time well spent”) positions them on the lower half of the spectrum.

In her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, Harvard’s Shoshana Zuboff argues that this business model — invented by Google, replicated by Facebook, and now being implemented across the board — is at the core of a new mutation of capitalism that is based on commodifying and extracting surplus from people’s personal experiences in the same way that companies did when labor and land were commodified with the intention to extract value at the early stages of laissez-faire capitalism. In this most recent mutation of capitalism, the core conflict is no longer between labor and capital, but between watchers and watched. Who is being watched? You and me — in other words, just about everyone in the system who is using digital technologies. Who are the watchers? The tech companies whose business model relies on user surveillance, on data analytics, and on selling predictive data to manipulate people’s behavior. The two main forces currently advancing this surveillance-based super-centralization of our societies are the Chinese government and Silicon Valley–based Big Tech corporations that use their de facto monopoly of power in ways that stifle competition, undermine democracy, and harm the well-being of all.

On the upper end of the vertical spectrum are multilateral platforms that focus on bridging the ecological, social, and spiritual divides of our time through new collaborative arrangements, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Climate Agreement, or the Wellbeing Economy Alliance (WEAll). Country-level examples include Costa Rica and the Nordic countries, all of which rank high on measures of societal well-being, health, learning, and happiness.

Looking at economic development through the lens of these coordinates allows us to notice a few things:

· The vertical axis location of your country or company, whether on the lower or upper half of the spectrum, reflects your answers to the following three questions: (1) How sustainable is your business model: how does it address the ecological divide? (2) How inclusive is your business model: how does it address the social divide? (3) How generative is your business model: how does it address the learning challenge — i.e., how does it enhance co-creativity for people in the community? Sadly, current economic and business models mostly ignore these questions and therefore are unconsciously biased toward operating on the lower half of the spectrum.

· If you want to move your organization or economy up on the vertical axis, it takes real work. You need partners, tools, new economic thinking, and new collaborative capacities to put such an intention into practice.

Which brings us to the related third axial shift: the one in learning and human development.

6. The Axial Shift in Learning and Human Development

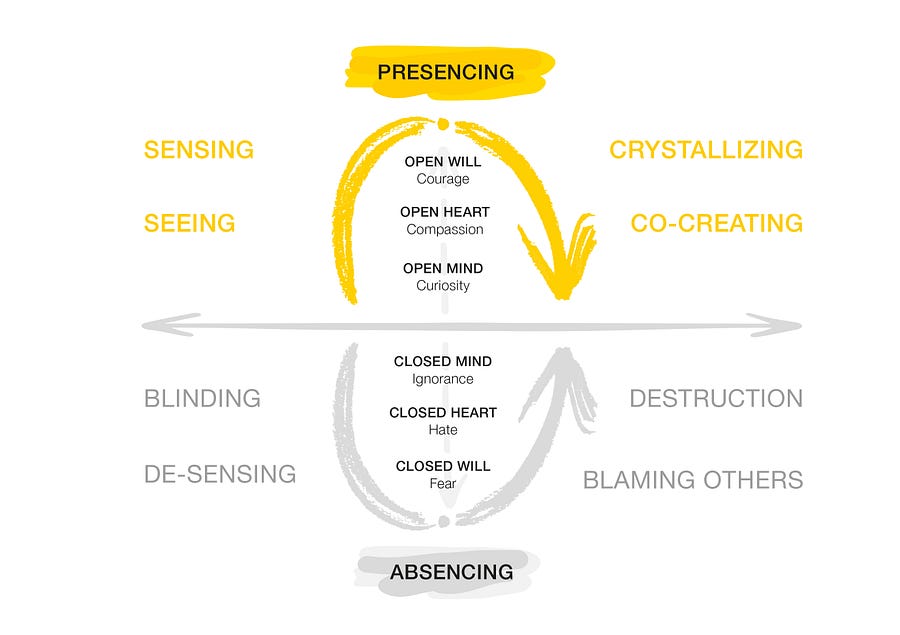

If we double-click on the two axial shifts described above — in politics and in the economy — we see that their underlying logic of human development is the same: the entities on the lower half of the vertical spectrum are operating on a social field that functions by activating ignorance, hate, and fear — the closing of the mind, heart, and will. The entities on the upper half of the vertical spectrum, however, are operating in a social field that functions by activating curiosity, compassion, and courage — the opening of the mind, heart, and will.

Figure 3 shows that the social fields that we see enacted through the axial shifts in politics and in our economy manifest through the same behaviors and the same deep operating system. Consider the examples of U.S. politics, Big Tech, and Big Oil.

· Denial. (1) Even though the United States is already suffering all the symptoms, the public conversation is still unable to address the elephant in the room: climate change. Big Coal and other allies of the Koch brothers successfully funded and built the climate denial industry that has undermined the credibility of climate science by focusing on sowing “doubt” in climate science.

(2) Post-truth politics. In his first 827 days in office, President Trump has made more than 10,000 false and misleading statements, without any toll on his popularity among his supporters.

(3) Social media. According to a recent MIT study, false information on Twitter is 70% more likely to be shared than accurate information.

· De-sensing. (1) Digital echo chambers. Social media algorithms tend to surround us with information that reconfirms our existing biases and opinions, thereby accelerating the disintegration of society into polarized groups that can no longer talk to each other.

(2) Empathy. Among college students in the U.S. empathy has dropped by 40% in the years since social media became a means of communication.

· Absencing. (1) Mental and emotional health. There has been a massive increase in mental and emotional health issues among young people worldwide. In the United States, 20–30% of teenagers show symptoms of depression and anxiety disorder.

(2) Multilateral international Institutions are being undermined by the actions of the U.S., which has pulled out of the Paris Agreement, ignored the World Trade Organization, and defunded the United Nations.

(3) Facebook is undermining the essence of western democracy by collaborating with the Russian government and U.S. billionaires to support far-right political views and parties in the U.S., the UK, and Europe.

· Blaming others. (1) Mexicans and immigrants are blamed for border problems that have nothing to do with them.

(2) Facebook has hired companies to deflect criticism of Facebook by falsely claiming the criticism was funded by George Soros.

· Destruction and Self-Destruction. (1) The U.S. is actively dismantling the Environmental Protection Agency.

(2) Violence in Germany against refugees is strongly correlated with the use of Facebook: the higher the use of Facebook, the higher the violence against refugees.

For all countries that find themselves trapped in the dynamics of absencing (the lower half of figure 3), the question is: How do you move yourself up the vertical axis as an individual, as a team, as an organization, as an ecosystem, and even as a country? What does it take?

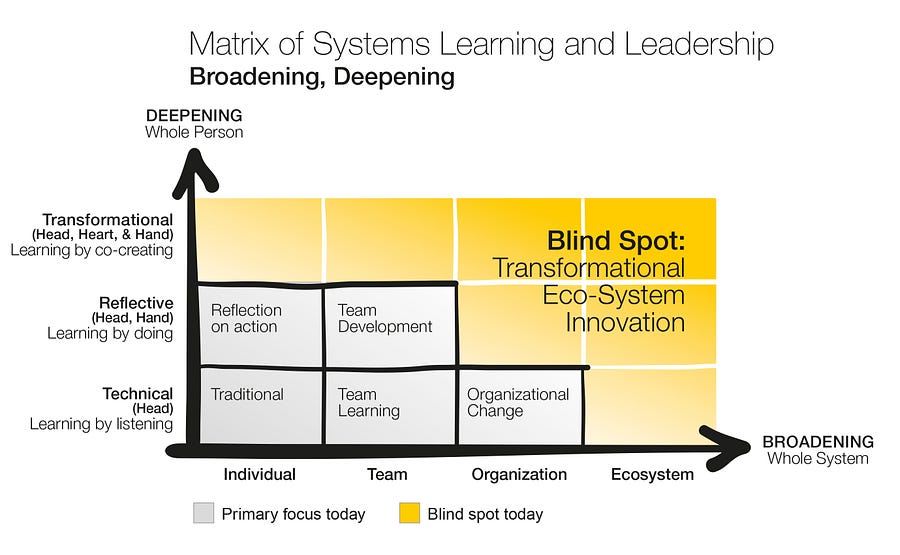

What it takes is not only a profound upgrade of our economic and political operating systems, but also of our deep learning environments (see figure 4), as explained in more detail here.

The bottom line of figure 4 is this: In order to respond to the major transformation challenges of our time, the focus of our current learning and leadership environments needs to broaden (across the horizontal) and to deepen (across the vertical axis), that is, to move from the bottom left to the entire matrix of figure 4, in particular to the top right corner.

7. The Nordic Secret: Can We Take It Global?

What do the youth-led movements around climate change, the rise of the Greens, and the vertical shift in politics, economics, and human learning have in common? They are all different expressions (or “faces”) of an underlying opening of awareness and shift in consciousness — the beginning of a global movement to regenerate and upgrade how our civilization operates: our economic, our political, and our learning systems.

That shift and opening process may well be the most important, yet least told, story of our time. To broaden and deepen that process requires enabling infrastructures — similar to the Green New Deal but applied towards massively upgrading our deep learning infrastructures in ways that make them accessible to all.

Can that be done? Of course. We just need the political will and our collective imagination to make it work. It has been done before, in the Nordic countries, where it produced one of the world’s most remarkable economic and societal turnaround success stories. In their book The Nordic Secret: A European Story of Beauty and Freedom, co-authors Lene Andersen and Tomas Björkman argue that the story of the Nordic countries — which encompasses a move from extreme poverty to ranking top of the pack in terms of well-being, happiness, health, and learning outcomes — can be traced back to a deep learning intervention in the 1860s by founding the Danish Folk High School.

The Folk High School made available a holistic learning model of integrating head, heart, and hand — largely inspired by German philosophers and poets such as Fichte, Schiller, and Goethe — to everyone. That model soon was adopted in Sweden and Norway and later on in Finland, too. In all of these countries the Folk High School provided a social and spiritual foundation for building vertical literacy — that is, for developing and integrating the whole human being in terms of head, heart, and hand in the context of the real life challenges of the community. The Danish Folk High School also inspired the foundation of the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, which was instrumental in training Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, and other key figures of the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and ’60s.

What would it take to update what the Folk High School did for the Nordic countries and make it accessible globally to the emerging youth movement and to everyone interested in activating such a deep learning cycle?

Global movements need enabling infrastructures, just as Rosa Parks had with the Highlander Folk School. What might that look like today? Over the past few years, my colleagues and I have been prototyping with such an enabling, scalable infrastructure using the MITx u.lab platform to deliver radically decentralized MOOCs (freely accessible “massive open online courses” that are navigated and owned by a global eco-system of local change makers and their communities), as well as the Presencing Institute platform for helping teams to move their idea into action through the Societal Transformation Lab (u.lab-S).

The results have been encouraging and involved more than 130,000 registered users across 186 countries. The key to further activate the above described global shift and movement requires us, among others, to cultivate our interior condition as change makers in order to engage with the symptoms of absencing and Trumpism in ways that keep our attention focused on where our intention lies: on bridging the ecological, the social, and the spiritual divides in all our individual and collective actions.

If you are interested in further exploring these ideas, join our monthly conversation series Dialogues on Transforming Society and Self (DoTS), or find us on www.presencing.org and www.ottoscharmer.com.

I want to thank my colleagues Rachel Hentsch and Sarina Bouwhuis for commenting on and editing the draft, as well as Olaf Baldini (fig. 1, 2, 4) and Kelvy Bird (fig. 3) for creating the figures in this column!