I first met Johnny Agar in July 2016 when he was a 22-year-old junior at Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, majoring in sports management and business. During that conversation, I realized we shared the same weakness.

Eating too much ice cream.

A few months later, when we bumped into each other at an event in New York City, I realized something else.

We are both DNFs.

I got mine when I Did Not Finish the Bethany Beach Triathlon, a .62-mile swim in the Atlantic Ocean, an 18.5-mile bike, and a 4.6-mile run. I took too long during the swim and the bike and there wasn’t enough time for me to do the run. Johnny got his at the IRONMAN World Championship in Kona, Hawaii, in 2016, comprising a 2.4-mile swim in the Pacific Ocean, a 112-mile bike, and a 26.2-mile run, one of the most difficult athletic events in the world.

Too much ice cream, and I can’t fit into my skinny jeans.

Johnny?

Staying as light as possible is critical in order for his father, Jeff, 55, to pull him in a boat during the swim and in a chariot during the bike, and push him in a chair for nearly 26.2 miles before Johnny stands up and uses a walker to make his way to the finish. At Kona, they were pulled off the course during the bike missing the halfway point cutoff unable to overcome the treacherous winds and brutal heat.

Johnny and Jeff are TeamAgar.

Maybe you’ve seen their amazing pictures and videos – father and son competing in marathons and IRONMAN triathlon events – or maybe you’ve seen Johnny in Under Armour’s new #WillFindsAWay commercial narrated by Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson featuring Johnny and seven other athletes.

Johnny was born premature and has cerebral palsy, which affects the part of his brain that controls his muscles, including voluntary movements and reflexes. In Johnny’s case, the disorder does not affect his speech, which may be why his least favorite event in a triathlon is the swim. A very chatty guy, that’s the only time during the race when Johnny is unable to speak – to his father or in response to the crowd.

Johnny has said publicly that walking a mile for him is like running a marathon for most people. Over the years, surgeons have performed numerous procedures on Johnny’s legs and on his eyes, and he has a shunt that drains fluid from his brain.

As someone who turned to endurance exercise later in life, in my mid-50s, and as a person who identifies as an accidental athlete, I am keen on learning from the elites. One thing is to know when to stop exercising instead of pushing through. Most of us have a hard time with this and spend more time than we should dealing with repetitive injuries as a result.

But here’s what I’ve learned from Johnny.

The gift of failure and the beauty of life. The awesome joy of what it must be like to possess the soul of an athlete.

Recently, I was on the phone with Johnny talking about TeamAgar’s finish, within the final minutes of the race cutoff, of Memorial Hermann IRONMAN Texas on Saturday, April 28, when he brought up failure. Like many other fans, I was using the IRONMAN tracker to watch the Agars’ progress but got concerned when the updates stopped 17 miles into the run, the last leg of the triathlon event. I was worried they didn’t finish and was afraid to text Becki, Johnny’s mom and the person who heads up his crew of coaches, trainers, and physical therapists.

“What was your finish time?” I asked Johnny.

“I have no idea,” he laughed.

“Was this your first finish since the DNF in Kona?” I asked.

“Technically, yes,” he said. “For a full IRONMAN I’ve never been able to walk the finish. Thanks to all the support from our crew and IRONMAN, you could definitely say #WillFindsAWay because I was able to walk to the finish line after my dad completed the marathon run.”

“That’s awesome! Congratulations!”

“I know failure is just part of the process,” Johnny was quick to add. “That’s why I am able to succeed. I am able to learn from my failures.” Becki told me Johnny experiences little failures every day, like dropping his hairbrush or his toothbrush.

“It’s not your challenges that define you,” Johnny said. “It’s how you deal with them.”

I asked Johnny about Saturday’s race and whether the team had made any changes in their training after Kona. I asked him what he’d learned from those experiences.

He said now TeamAgar has better equipment from Adaptive Star and BMW, as well as the myTeam Triumph organization, which Johnny and Jeff have been involved in since 2013, and Johnny began working with his coaches and therapists to understand where he needed to sit in the chariot and the chair during the race and how to be more aerodynamic. His transition coach, Terence Reuben, a physical therapist from myTeam Triumph, joined the crew in Houston as he specializes in chariots and pulling. Other physical therapists worked with Johnny during the transitions to stretch him and keep him hydrated. For years Johnny’s done all of his intensive therapy and training at the Conductive Learning Center in Grand Rapids, which is where he first learned to walk. He continues to train at the Center.

Since Johnny’s brain doesn’t automatically communicate with his muscles, Johnny spends a lot of time focusing on telling his brain what it needs to do, he said. Among other things, his therapists, including his mother’s cousin Janet and her husband, Chris, who traveled with the team to Houston, have taught him how to use his breath to stay focused on sending signals from his brain to his legs.

“I know more about my body,” he told me. “I’m continuing to work on my body mechanics and learning how to maintain my calm and focus on what I need to do.”

This turned out to be critical during Texas, Johnny said, because as they were up against the clock during the run and with the crowds cheering and no place to stash his chair until a quarter of a mile from the finish, he realized when he stood up, after sitting for 16 hours, that he wasn’t able to walk.

He said he blocked everything else out and slowed his breath, listening and feeling his body so he could fill his body with energy, give it oxygen. Only then did he begin to take steps and walk the .25 mile to the finish.

“I can get amped up,” he said. “So it was all about calming myself and breathing so I could focus on what I needed to do and to be sure my muscles were getting the correct oxygen flow.” Every few steps he let the crew know he needed water.

“I put my training into practice and that made me happy.”

The irony was that the team whizzed through the swim, with their fastest time ever. As Johnny’s coaches were getting the bike and chariot ready in the transition area, they heard a pop and a sizzle and worked quickly with the IRONMAN support staff to replace one of the tires on the chariot. What they didn’t realize, possibly because of the roar of the crowd, Becki told me, was that the chariot’s other tire had burst, too.

Apparently, Jeff pulled the chariot for 50 miles (about three hours) before the crew figured out what was slowing him down and repaired it. So we know where Johnny’s athletic genes come from.

Although they weren’t able to make the cut off time for the bike portion they were still able to complete the race.

Johnny has one more semester at Aquinas College, and from there he’ll pursue a career in sports management. As both a competitor and a gifted motivational speaker, and the newly named sports ambassador for the Cerebral Palsy Foundation, Johnny is an inspiration to thousands of people to pursue their goals and dreams despite any obstacles they might be facing. In our conversation in 2016, Johnny told me even as a little kid, and for as long as he can remember, he knew he was born an athlete. He just didn’t get the body that would have made it easier for him to play sports.

“I want people to know they don’t ever need to give up on their dreams,” Johnny said.

Before IRONMAN Texas, Under Armour CEO and founder Kevin Plank called Johnny to tell him how personally inspired he was by Johnny’s perseverance and stamina. Johnny said Plank told him he represents what Under Armour is all about and why he created the company, which flew the team, and all the equipment, to IRONMAN Texas in a corporate jet.

Building relationships with athletes is one of the greatest pleasures Johnny gets from competing with his father in sporting events. He’s one of them. Several Under Armour athletes are in regular contact with Johnny, including Michael Phelps, and he’s developed a friendship with Houston Astros pitcher Justin Verlander.

Johnny connected with Verlander in Houston where he attended an Astros game. I asked Johnny if Verlander had any advice for him before the race.

Johnny said he had lots of restaurant recommendations.

And one piece of advice.

“He told me to ‘hurl a gem,’” Johnny said. That’s baseball-speak for pitch a good game.

Around mile 19 during the Marine Corps Marathon a few months ago, when I was feeling nauseated, I pictured Johnny walking across a finish line, my go-to image for persevering.

Now, when I pull out my sports gear, instead of even questioning whether I belong, I’ll remember Johnny’s passionate, amped up voice in my head.

Don’t let your challenges define you. Hurl a gem.

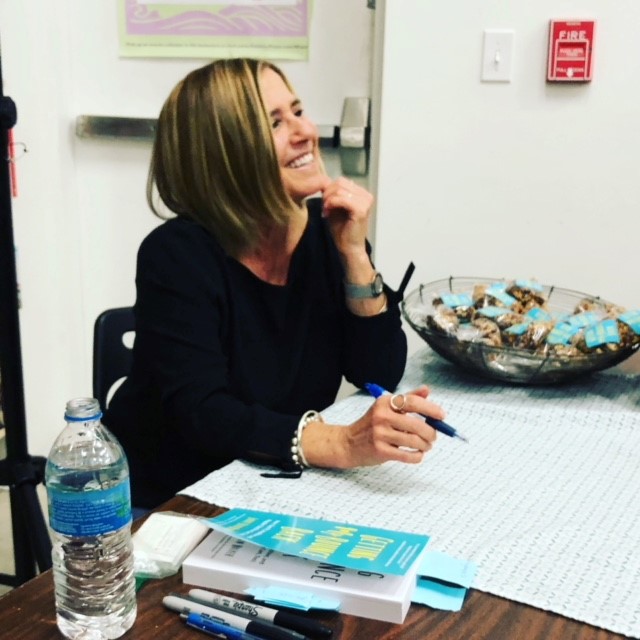

Carolee Belkin Walker is the author of “Getting My Bounce Back: How I Got Fit, Healthier, And Happier (And You Can, Too).”