“OK. But, Jane… who says that upside down will definitely be worse than right-side up?” He pauses for a breath to let that truly sink in. “Maybe,” he continues, “this is just evolution. Painful, yes. Scary, yes. But it could also be just what we need.”

Simon is my patient, no-bullshit-giving life coach, whom I met earlier this year mainly because (1) my law firm offers free therapy to its attorneys, and (2) I never turn down free stuff. I called him because it was one PM on a Tuesday and I found myself crawling back to bed yet again, seeking refuge from the endless merger agreements I needed to redline and the constant stream of cataclysmic news alerts bombarding my phone. The world is turning upside down, I told him, and I am utterly exhausted. Exhausted from all the nights I have lied awake lately, wondering when I will get to hug my friends and family again. Exhausted from all the pain—all the lives and day-to-day normalcy we lost in this weird and senseless pandemic. Exhausted from all the anger, absorbing the depths of our heartbreak as we reel from seemingly endless blows of systemic racism.

Perhaps Simon is right (I pray that he is). Perhaps, on the other side of all this, we will eventually find that upside down really was exactly what we needed. History proves that calamity is often the catalyst for change, after all. But none of this changes the fact that the last couple of months have just plainly sucked, with all the utterly terrifying things going on in the world awakening our inner demons—demons like Fear, Loneliness, Anxiety, Insecurity, and Depression… and all the guys we face behind closed doors but do not speak openly about.

As a lawyer and former Wall Street analyst, I know I am far from the only one who has ever confronted these guys. We hyper-achieving, Type-A professionals tend to be fraught with higher levels of depression and anxiety as is, and these challenges only multiply once we sprinkle in the additional dimensions of being minority or immigrant or female (or all of the above, in my case). For instance, even before the inexplicable mess of 2020, Asian American attorneys like myself consistently reported higher rates of mental health challenges than the broader population as a whole, with half of us reporting some history of moderate to severe depression or anxiety.

These hiccups in our emotional wellbeing are perhaps rooted in the pressures of our culture, particularly among Asian Americans: The pressure to be perfect and pleasing, the pressure to achieve, the pressure to obey, the pressure to prove our self-worth to the world with fancy degrees and fancy paychecks and fancy houses. We worship at the temples of Achievement and Perfection from day one, scoring straight-As and first-chair orchestra seats like all “good Asians” do. We are taught to constantly look upward to the next rung on the ladder—the first-place trophy, the valedictorian speech, the Ivy-League degree—and seek nothing but the best at all costs. And when we place external validation on a pedestal in this way, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to accept that we are inherently enough: There will always be something more to achieve—to close the ever-persistent gap between who we are and who we “should” be. And wherever that gap persists, it becomes all too easy for us to turn on ourselves—for all of those pesky insecurities and self-doubts to swoop in and take residence in our hearts.

I know these pressures and inner demons all too well; it is only through my prior battles with them that I have learned to better withstand the curveballs life has thrown at us lately. For nearly all my life, my ambition was my master: Its militant discipline and rigid motor were what propelled me through Yale College and Harvard Law and my shiny careers in law and finance. Fourteen-hour workdays and ten-mile runs were my regular repertoire. I was so proud of how fiercely disciplined and accomplished I was—feeding myself on other people’s compliments and admiration, never once considering the idea that my drive stemmed not from inherent greatness but from inherent fear. Fear of being unworthy. Fear of what it would mean if I did not have that perfect resume, that perfect body, that perfect hair. Fear of what it would mean if people didn’t think I was likeable or successful or beautiful. And so, I should-ed the crap out of myself: By the time I approached thirty—the age I always equated with fully formed adulthood, as if “being an adult” were some kind of destination—I made it my business to have everything I was told I should want. That perfect-on-paper fiancé—a tall, broad, Yale Law grad in my Summer Associate class—who was already researching good suburban school districts for our future kids. That shiny, six-figure lawyer job at a big prestigious firm in New York City, which made my loving Korean parents beam with pride. That sleek junior-one-bedroom a block away from Central Park, brimming with the latest and greatest Vitamixes and Dysons one could possibly need for the said children she was expected to have.

But… was I actually happy?

This question astounded me at first. Because for thirty years, I actually never paused to ask what would even make me happy in the first place. I simply never gave myself permission to decelerate my Energizer-bunny pace of life; I was too busy checking off to-do lists, pleasing bosses, acing exams, tracking my sugar intake, and applying no fewer than five layers of SPF. Whatever made me smarter, better, richer, thinner, more successful, and more beautiful were the only matters worth considering. But questions of happiness? Matters of the heart? Well… those things just got in the way, slowing me down and threatening to stain that perfect image I had hustled to project out into the world. Any doubts I had, I numbed alone in my darkest corners, far away from prying eyes, before cajoling myself to sleep and pulling it all back together the next morning with a plastered smile on my face. I never allowed myself a moment to slow down, catch my breath, and ask whether the life I was hustling so hard to build was truly my own.

Silencing my heart in this way worked ridiculously well for a long time… until suddenly it didn’t. Perhaps it was inevitable. Or, perhaps, all the additional pressures I began facing—the grueling big law hours, the daunting foreverness of a looming marriage, the unforgiving expectations on minority female professionals in their thirties—were heavy enough to finally tip the scales for me. Regardless of the exact reason, however, the end result was very clear: My heart—after being ignored and silenced for all my life—finally had enough. It began to betray me, cracking open under all that pressure and allowing Depression to gallantly swoop inside.

Once nestled, Depression swiftly swallowed me whole with its three vicious heads. First came Shame. People who equate Depression with pure sadness don’t immediately understand this: It is actually Shame, not sadness, that initially gut you. Shame was cruel and ruthless to me—its sharp tentacles riling up every deep-seated parcel of self-doubt and making it impossible for me to function any longer. It played highlight reels of the most flawed parts of me—all the ugly ways I was selfish, petty, mean, unforgiving, utterly unlovable—and demanded that I reckon with them. That I stop cowering away from the weak, imperfect, and never-good-enough woman I really am. It was pathetic, Shame said, that I needed to armor myself with degrees and money and makeup just to prove to the world that I was enough. Parading around and showcasing to the world only the best parts of me—the easily digestible parts of myself that were smart and pretty and flirty—didn’t I know that’s not me? Didn’t I know that I will never be enough, no matter how much I try?

Once Shame sufficiently shrunk me down to size, Depression then unleashed Guilt. And Guilt was all too happy to shatter me and slap me around, doing all sorts of weird things to weaponize my mind and proving what a spoiled jerk I was. Because how dare I have second thoughts about my life—the very one I had hustled so hard to create? How could I be so entitled? Yes, perhaps I was discovering that I may no longer want to be engaged to this perfect-on-paper man … but didn’t I know how hard it is to find a suitable life partner? Didn’t I know how many single women in New York would trade places with me in a second, sporting that huge diamond ring signifying evermore security in the future? And speaking of security—yes, perhaps I should have figured that corporate tax law was not going to be my jam… but didn’t I know how lucky I was to have that steady, plump paycheck coming my way twice a month? All adults are tired and bored by their jobs—that’s part of the deal. Just like taxes and student loan payments and, one day, rearing children of my own—all these things, grown-ups just do. If I have any doubts, swallow them. Because who was I to say that all this wasn’t enough for me? Who did I think I was?

Depression’s third and final weapon was Despair, which was one of the most powerful yet ephemeral, all-consuming yet erratic, familiar yet foreign experiences I had ever tasted to date. It was so physically crushing that I regularly went to bed at night resting my palm across my heart—afraid it might actually break inside my body—and wondering if this was just the way I was going to end all my days from now on. I still found familiar glimpses of myself, even in the thickest part of this fog—like, for instance, the merciful snippets of quiet that greeted me every morning, if only for a few seconds, before my body realized I was awake and once again blanketed itself with the sorrow and loneliness it had hung out to dry the night before. For the remainder of my hours, though, I carried Despair with me, crushing myself under its hefty weight wherever I went and expending every ounce of energy to just survive the day. I knew on some level this was not me but rather some other energy taking over me, but even that I was not entirely certain—maybe this had just been me all along. I was not entirely certain of anything, perhaps, other than the cruel reality that I simply had nowhere left to go. I was already parked at my last resort.

It was only when I finally hit the darkest depths of Despair—utterly depleted, immobilized on the floor of that sleek Upper West Side apartment, accepting nothing else but the fact that I was alone and cornered—when my heart began speaking to me again.

And I actually began to listen, for the first time in my life…

Because I no longer had the energy to run away from myself.

Because it was finally quiet enough for me to hear my true voice.

Because, well… what other options did I have?

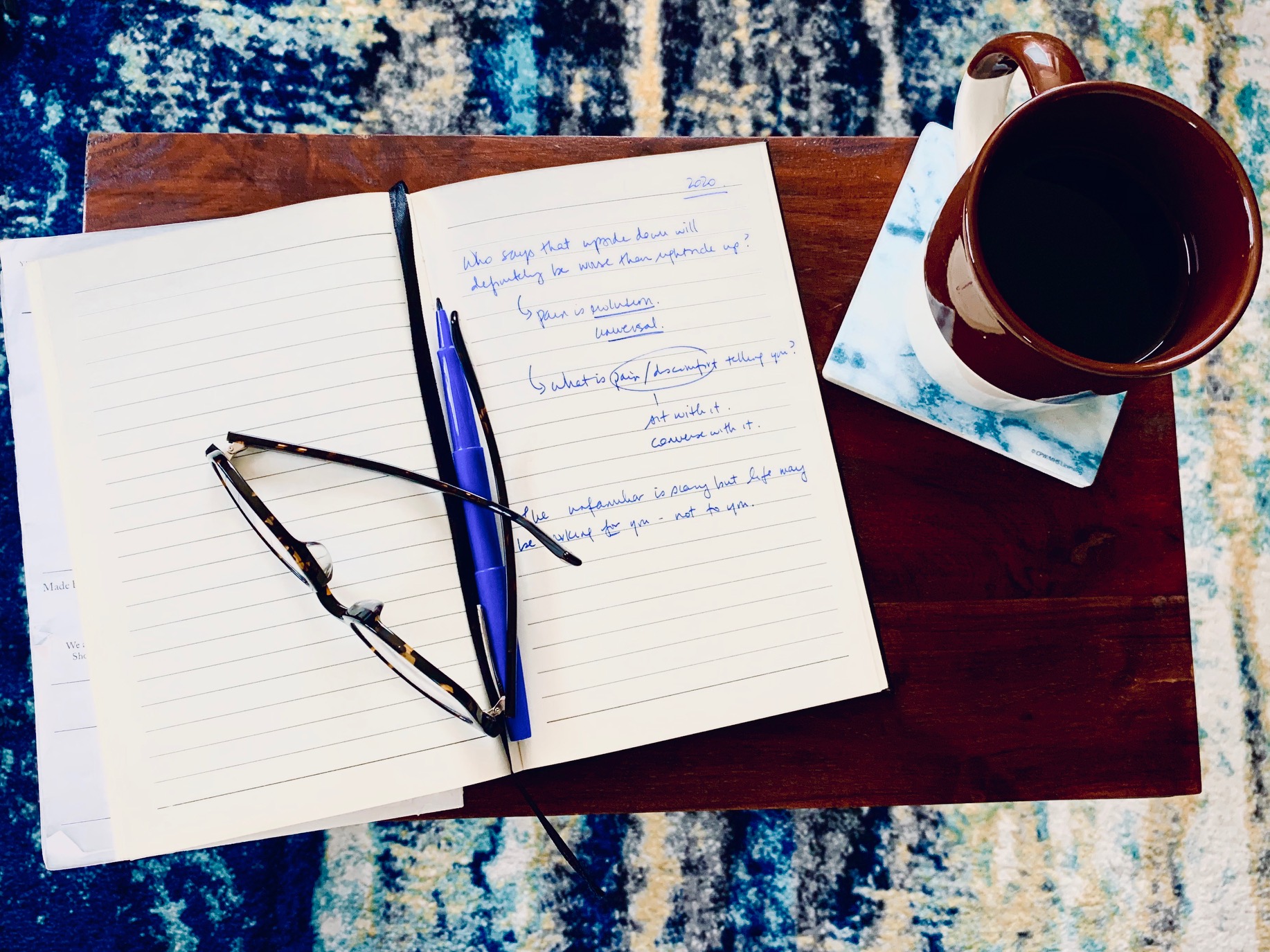

That conversation started off so small, so plain—because small and plain were all I could afford at the time. I did not know exactly what my heart needed to be happy, but I knew it needed something different—something more me. And since my evenings and weekends were still at the mercy of big law, I began waking up at the crack of dawn—well before anyone woke up to start demanding anything of me—if only to buy the simple privilege of not being accountable to anyone else for just a sliver of my day. And with that new pocket of time, I exercised, read, journaled, ran, prayed, painted, danced, meditated, or took aimless strolls around my neighborhood. Other times, I simply went back to sleep. I also began setting a standing calendar appointment every day at four PM, simply to pause for fifteen minutes and give myself permission to do whatever else I wanted—like fetching an oat milk latte or calling an old friend for a quick hello. I started going to therapy and got in touch with my inner child. I chatted up my mom and dad, my best friends, my ex-flings, my coworkers, my bosses, my former professors, my other Simons—anyone else who might know a thing or two—and asked how they managed to figure all this out (answer: no one really has). I filled my commutes with podcasts and motivational speeches from every spiritual and religious teacher I could find. I sent out random affirmations out into the world all throughout the day, asking the Universe for inner peace and grace. I taught myself how to do whatever I wanted purely for the pleasure of it—without any regard for its purpose or end goal—for the first time in my life.

Nothing changed at first. But little by little, over the next few months, two truths began to surface in my heart:

- The bravest and kindest thing we can do for ourselves is to embrace one simple truth: Being human ain’t always pretty, and that is totally OK. It is OK not to be OK sometimes; contradictions are simply part of our human condition. For three decades, succumbing to the fullest range of human emotions—or projecting any image other than a perfectly-put-together one—was a thing I never had desire nor ability to do. But the simple truth is that I was not given this life solely to achieve, produce, perfect. Instead, I have the honor and privilege of participating fully in the human experience—and that includes not just the pretty parts I spent my entire life meticulously showcasing to the world but also the scary, ugly truths of my humanity that I had muffled for way too long. I can own the fullest spectrum of the human experience by embracing all possible truths about myself—particularly the ones I find difficult to love. Because I am in equal parts my weakness and my strength, my pain and my beauty. It is in these contradictions, then, where my heart and Self-Love actually expand.

- Sometimes, as Simon says (ha!), pain is nothing more than evolution. And no matter how lonely or scared or anxious we may be at times—particularly right now, given the state of our world—we are never alone in our pain. In many ways, Depression ended up being a cruel savior: It brought me to my knees just to show me it could, to force me to sit still and begin listening to what was going on in my heart. It was what I needed to (finally) step out of the comfortable confines of my mind and scream for mercy when I could no longer take it anymore. And the more I screamed—the more I drew the curtains on all the self-doubt and insecurities and fears I thought were uniquely and shamefully mine—the more I learned that I was far from alone. Because pain resides within all of us. In this way, the more I released my inner Shame and Guilt and Despair, the less they ended up controlling me. The more I talked about my fears and self-doubt, the more I realized just how mundane and universal they are to our humanity. I had spent almost my entire life terrified of what it would mean if I accidentally revealed my inner battle scars—only to look around and see that everyone else had been hiding the same damn wounds this whole time.

Ultimately, my past battle scars have better equipped me to withstand the whirlwind of pain and confusion life has thrown at us this year. It is not that I am now impervious to Depression or Loneliness or Insecurity; it is just that I can better recognize these guys for the pesky, temporary intruders they are when they occasionally come knocking on my door. I can accept Pain and Fear and all of their ugly cousins as mere co-habitants of my human journey—alongside Joy, Happiness, Love, Gratitude, and Beauty—and appreciate that it is only through understanding pain that I can truly find peace.

All this is why I believe it is more important than ever for us to lead a different, more authentic, dialogue here. There is not much I am certain of these days—it really does seem like the world has turned upside down and, Simon’s wisdom notwithstanding, upside down does genuinely feel crappy at times. But if there is one thing I know for sure, it is this: There are too many of us who are sitting at home in pain right now. There are too many of us who need a reminder that we are not alone—that this too shall pass. There are too many of us who can afford to be a lot kinder to ourselves in this moment—to let go of who we think we “should” be and learn to see all the beautiful contradictions of who we truly are.

So guys, let’s step it up and each create that safe space for one another. Let’s give up the jig and give each other the freedom to show up imperfectly—to ride out the storms together in a time when we all need a reminder we are not alone. Because we have all been there, in some form or another.

Because it really is OK not to be OK.

This essay was originally published by the Asian American Bar Association of New York.