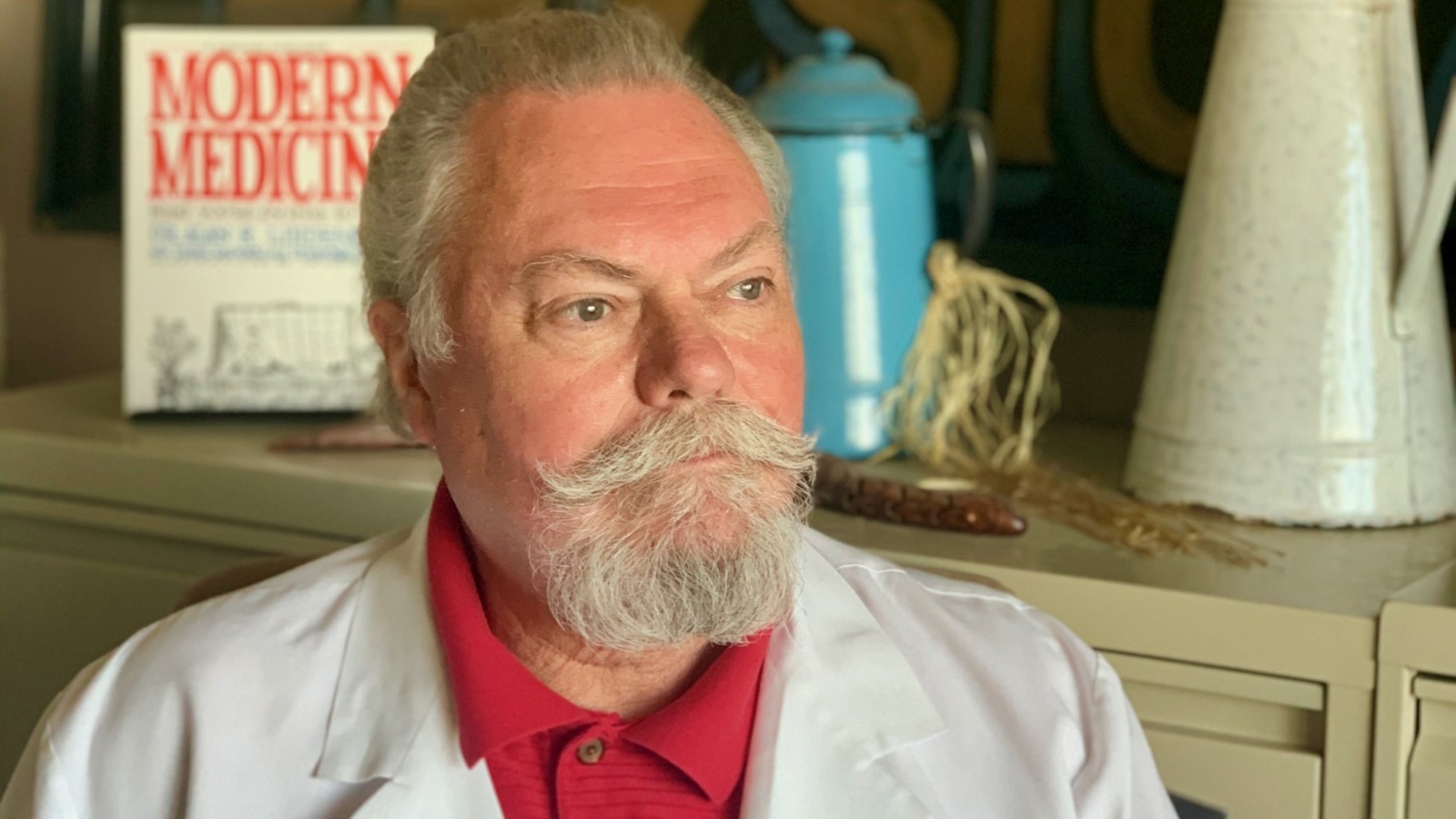

Dr. Alan Lindemann, felt a calling to become a doctor from a young age and throughout his life has learned how to provide high-quality care to his patients.

Can you tell us a story about what early experiences brought you to choosing a career in the medical profession?

Many professionals, be they lawyers, doctors, or teachers, usually come from families of lawyers, doctors, or teachers. If you think about it, there’s a good reason for this. Children grow up learning without actually being aware of it, almost by absorption, many of the traits and issues surrounding those professions. So if they choose to follow their family careers, they already know a lot of the lingo and what goes with the territory. I have a son and a daughter who are doctors, but I grew up in rural North Dakota without any role models for becoming a physician.

So how did I slip into the role of a medical student, eventually completing an obstetrician/gynecology residency, and go on to deliver 6,000 babies with no maternal deaths? Nodakers, as residents of this state are called, are known to be hard workers. Many grew up on farms where, like physicians, the work never stops and they are always on call. I didn’t go to private school, but instead attended a country school where I had a terrible time with math. I knew I didn’t want to farm, although I spent plenty of time in the hot sun tilling corn. There was no air conditioning in my home or in my grandparents’ house on the farm next door. Air conditioning was holding the water hose over your head and letting the cool well water run down your body and soak your clothes.

Until I was 11 years old, I lived on a small farm with animals and birds. I was the one who took care of the animals when they were hurt and when they gave birth, so I had experience taking care of health problems with the animals, although I never wanted to become a veterinarian.

A nearby college (in that day, a teachers’ college) in Valley City was the nearest college to where I grew up. I didn’t stay there long because I had no interest in becoming a public school teacher. My great grandparents had migrated to North Dakota from Germany. Like many rural areas of North Dakota, native languages were still spoken in the local restaurants and stores. I enjoyed hearing the German of my ancestors, and I was good at learning languages, so transferred to the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks where more languages were available for study. I decided to major in languages and enter the foreign service.

Actually, I had decided to become a doctor at age 12, but for years I kept that a secret. After all, what qualifications did I have? I could pretty much guess what people would say had I voiced this notion. Besides, I was no good at math, so I didn’t know how I would get through trigonometry, calculus, or physics — subjects which weren’t available in my rural high school at that time.

Even though I enjoyed studying languages that first year of undergraduate university education, a part of me still wanted to become a doctor. I always cared about the welfare of other living beings, and actually finally took the step to change my major to pre-med. At that time, being an M.D. was still considered a noble profession. In the fall of 1970, I made the decision to switch my major to pre-med and I started preparing for getting into med school.

Can you share the most interesting story that happened to you in your career as a doctor?

I did once have a pregnant woman come to see me in labor. She didn’t know she was pregnant and she didn’t know she was in labor. Yes, these kinds of things do happen.

Can you share a story about the funniest mistake you made when you were first starting out on your career? What lesson did you learn from that?

Hospitals have increasingly become invasive in their monitoring of women in labor. We know that frequent pelvic exams on laboring women simply leads to a greater likelihood of infection, and fetal monitoring increases the likelihood of a c-section. When I joined my first practice after graduating from my residency, I worked with an older obstetrician who said the best things to do with your hands during labor is to sit on them. He was right.

To #DareToCare means to survive and thrive in today’s medical world. How do you take care of yourself? What’s the routine you must do to thrive every day?

For relaxation, I take care of my chickens. I always enjoyed taking care of them as a child, and I still enjoy watching a flock interact much in the way people do.

I write a series of letters to my God-daughter in my latest book. In that same vein, what are 5 things you would tell your younger self?

a. Believe in yourself. I had decided to become a doctor when I was 12 years old, but for years I kept it a secret, worried about what my family would say.

b. Many professionals, be they lawyers, doctors, or teachers, usually come from families of lawyers, doctors, or teachers. If you think about it, there’s a good reason for this. Children grow up learning without actually being aware of it, almost by absorption, many of the traits and issues surrounding those professions. So if they choose to follow their family careers, they already know a lot of the lingo and what goes with the territory. But I had no model growing up and had to observe and learn how to get into medical school. If you had no model growing up, find a mentor.

c. I took a job as an orderly at a starting wage of 95 cents an hour, or almost seven dollars a day after taxes. Since medical students often observed the patients I worked with, it gave me an opportunity to learn about med school by talking with them. What I learned at that job compensated for the low pay I received for what I was actually hired to do.

d. Teaching is fundamental to almost everything you will do. I didn’t think I wanted to be a teacher, at least in a public school classroom. But I found out that teaching medicine to interns and residents was profoundly rewarding. Teaching comes in many shapes and sizes.

e. The right answer isn’t always what you think it is to others. At one point I went to talk to the Dean of Students about med school. He asked me why I wanted to become a physician. I told him I wanted to be a different kind of doctor than the ones I knew. I would be interested in my patients and care about them. He didn’t say anything to me about my answer, but it was easy to see that this answer, in his mind, wasn’t the right one. I was sure not to say anything about this in my interview with the med school admission board. Indeed, the one candidate who said they wanted to be like Marcus Welby was never seen again.

How can medical professionals reclaim heart-based healing amid pandemic, political, and other pressures?

We are unfortunately in about as heartless a medical environment as can be found, and it far predated the pandemic. There is a growing group of physicians who practice what is called “direct primary care.” They don’t take insurances but provide 24/7 care and access to their cell phones for a monthly subscription. You can see them the day you call for an appointment and they can take an hour to visit with you to find out what’s wrong, if need be. They provide the kind of care physicians used to provide their patients. The key to good health care is the primary care provider who knows the patient and family and can refer to specialists as needed. Corporately controlled health care exists to make money any way possible, and that is often not in the patient’s best interest.

Is there a particular book that you read, or podcast you listened to that really helped you in your work as a healthcare professional? Can you explain?

Dr. John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist, lived from 1907 to 1990. He spent his entire professional career studying and treating children and adults who had lost their primary parent at an early age. This is especially hard on children who lose the parent of the same gender.

Bowlby found that often these children wound up in prison. But that’s not always the way it must be. One can learn to parent oneself.

My father passed away when I was 11 years old. I was an adult before I discovered Bowlby, but reading of his work helped clarify for me much of what I had gone through losing my father at the age of 11.

Because of the role you play, you are a person of great influence in the healthcare community. If you could inspire other doctors and nurses to bring change to affect the most amount of good to the most amount of people, what would that be? Said another way, what difference do you see needs to be made for our collective future?

Growing up in rural North Dakota and continuing to practice here, I have seen vibrant rural hospitals starve and die as physicians were banned by the government from owning hospitals and CEOs with accounting degrees took over healthcare, along with the insurance companies and pharmacological companies. Obstetrics have almost disappeared from the rural landscape, helped in part by ACOG’s refusal to board physicians who see men. In rural areas, the family practice physician needs to be nurtured, not driven out of practice by replacing them with the more inexpensive NPs and PAs. It’s not about healthcare, it’s about saving money for corporate owners of the system. There’s nothing non-profit about a hospital which pays a CEO an $18 million salary, even if the label says non-profit.

The rural hospital which does not supply obstetrical services because of the “risk” involved is simply putting the pregnant woman and her baby at great risk because of the distance that must be traveled to deliver. That is, the rural hospital, by refusing to accept what is essentially imagined risk, simply transfers what becomes a very real risk to the mother and baby, a risk which is far more deadly than the imagined risk of malpractice and high insurance costs. Birthing centers need to be established so women don’t have to travel hundreds of miles to have a baby. Obstetrics doesn’t have to be high risk in rural areas. Doing obstetrics badly is optional.

How can people connect with you?

They can start with RuralDocAlan.com, my landing page, which has links to my video courses, my blog, and my book “Modern Medicine: What You’re Dying to Know.” I am also forming a subscription-based support group, SuccessfulPregnancies.com. If you register at Rural Doc Alan, you will be sent a notification when Successful Pregnancies is live.