This article has been lightly edited to account for recent global events related to anti-Black racism, it was originally published via the Ajani Photography blog on Thursday, June 11, 2020, and was requested for publication through Thrive Global by Arianna Huffington. All photos are by Ajani Charles.

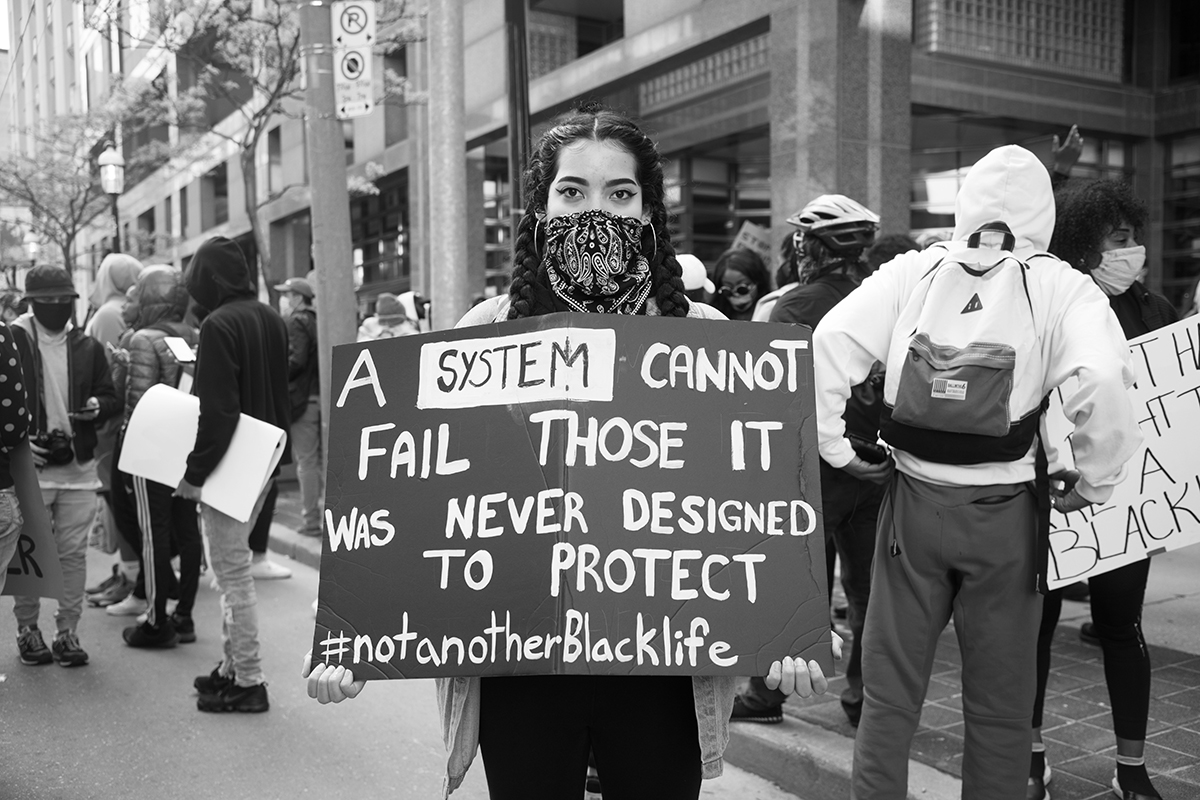

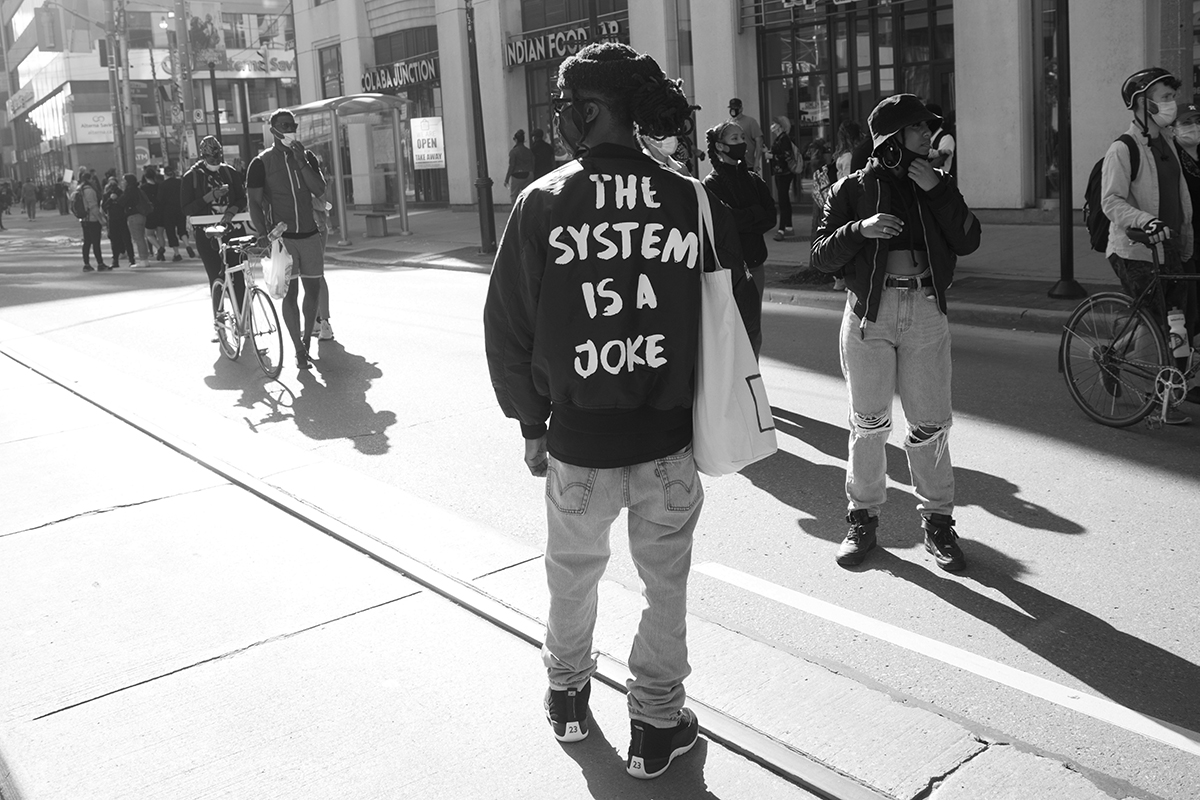

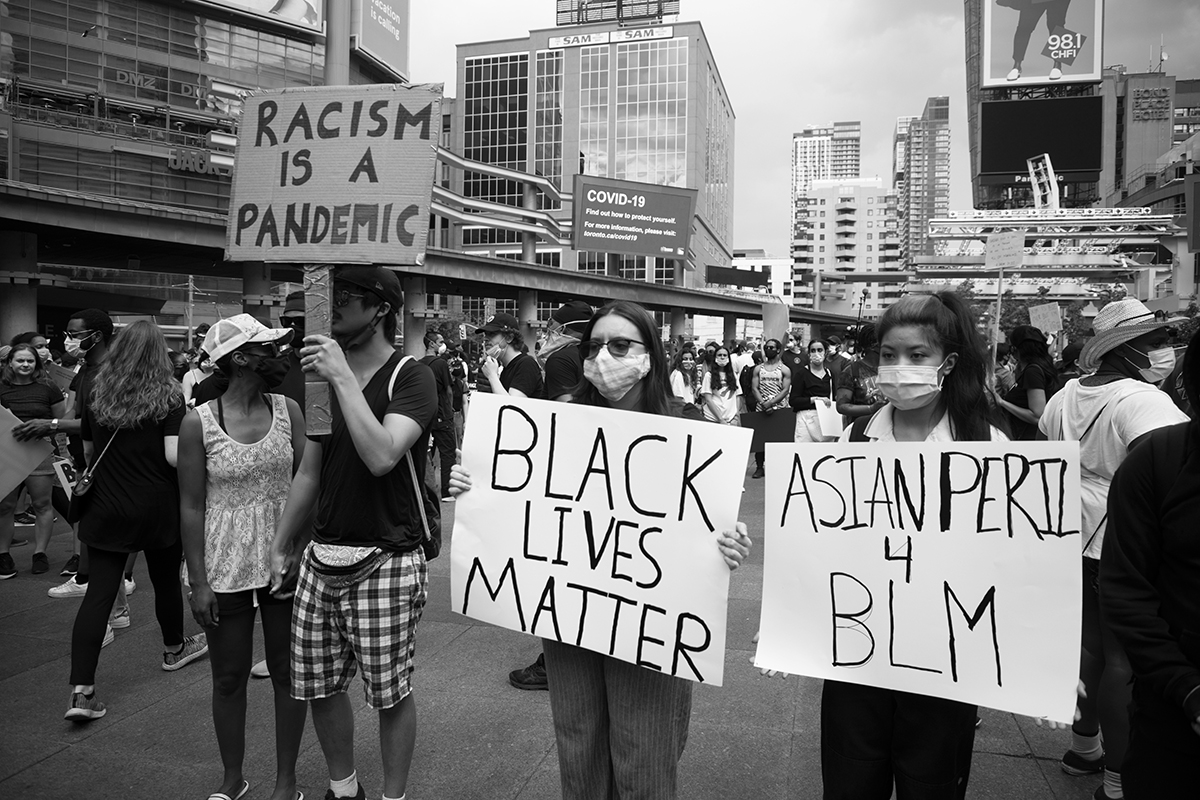

This article features my photographs of the recent solidarity marches and protests in Toronto, which have all been peaceful, and which have been organized by a group called Not Another Black Life, Black Lives Matter Toronto, and others.

The images are part of my commentary on the subject matter of this article and on many recent, disruptive and revolutionary events throughout North America.

My sense of my Black, Caribbean, and African identity has been woven from my life experience certainly, but also from the threads of symbols that consistently take me back to the origins of my family and ancestors.

My first name Ajani is Yoruba, it stems from West Africa, and means “one who takes possession” or “one who is victorious”.

My middle name Christophe was inspired by Henry Christophe, a key leader in the Haitian Revolution and the only monarch of the early nineteenth-century Kingdom of Haiti. I have a warrior’s name.

I was named by my father Asselin Charles, a professor of comparative literature and literary translator who has been fighting for the rights of Black people for decades.

My family is from Haiti, the first and only nation to have won its independence through a slave revolt that resulted in a 21 billion dollar debt to France. My photography company’s logo is a modernized version of the Ananse Ntontan, the West African symbol for creativity. My career-long support of the Toronto-based non-profit organization Stolen From Africa — an arts education company that promotes the cultural and historical awareness of the African Diaspora, is motivated by this shared awareness that I am a Black man and that my ancestors came from West Africa to Haiti via the transatlantic slave trade that resulted in the genocide of millions of Africans and atrocities too numerous and heinous to describe here.

I have experienced overt and covert forms of anti-Black racism throughout my life, and I have been racially profiled by police while driving and on foot. Even though I take full responsibility for everything that happens to me in life, in accordance with a number of principles first developed through stoicism, different forms of yoga, and existentialism, racism is an obstacle that all Black people must face nonetheless.

I have overcome and continue to experience a myriad of challenges throughout the process of forging a diverse and complicated career and establishing my presence in a number of interrelated industries.

Naturally, then, conscious as I am of my Black identity, the recent killing of George Floyd and the marches, protests, and riots that have followed in the United States and elsewhere have affected me deeply.

My reaction to these events is intertwined with my evolving sense of self in numerous ways.

The death of George Floyd is but the more recent reminder of the anti-Black racism and oppression that have been a constant in human history, virtually everywhere.

Here is an example from three millennia ago. Long before colonialism, long before Africans were brought to North America by force, in Vedic India, during the time of the Rigveda (circa 1000 BCE), there were two varnas or social classes: arya varna and dasa varna.

The distinction between the two classes or castes originally arose from tribal divisions. The Vedic tribes who descended from light-skinned Aryan conquerors that once resided in modern-day Iran regarded themselves as arya, otherwise known as the noble ones, and the rival tribes were called dasa, dasyu and pani.

The dasas were frequent allies of the Aryan tribes, and they were probably assimilated into the Aryan society, giving rise to a class distinction. Many dasas, who had dark skin like members of other tribes throughout Vedic India, were descendants of the original inhabitants of the Indus valley, and they were placed in a servile position, hence the eventual meaning of dasa as servant or slave.

The caste system, as it exists today, is thought to be the result of developments during the collapse of the Mughal era in mid-19th century and the rise of the British colonial regime in India.

Between 1860 and 1920, the British segregated Indians by caste, granting administrative jobs and senior appointments only to Christians and people belonging to certain upper castes. Social unrest during the 1920s led to a change in this policy.

From then on, the colonial administration began a policy of divisive as well as positive discrimination by reserving a certain percentage of government jobs for the lower castes, which usually comprised of Indian people with dark skin.

In 1948, negative discrimination on the basis of caste was banned by law and further enshrined in the Indian constitution. However, the system continues to be informally practiced in India with terrible social consequences.

So, dark skin, blackness if you will, has been discriminated against for a very long time. Such prejudice is quite apparent in Asia, where darker complexioned people are customarily assumed to be farmers or other workers who toil outdoors in the sun.

Ultimately, in Asia, dark skin is often associated with the lower social classes, with generally pejorative connotations.

My own experience in China testifies to the currency of such color prejudice in that part of the world.

I traveled throughout China in 2012, to work, and to determine if I would relocate there or not. This month-long journey was one of the most memorable experiences of my life. The Chinese people, by and large, were friendly and hospitable, and in many instances more so than any Canadian that I have interacted with.

Some went to great lengths to ensure that I did not get lost, that I got back to my hostels safely, that I had access to the technology that I needed, and that I lacked for nothing.

Occasionally, my exotic looks as a Black man drew people’s attention, as any unusual looking traveler in a foreign country would.

For example, while I was visiting Chengdu, in Sichuan Province, which is in central China, a group of girls followed me for many blocks, laughing and pointing at me, no doubt amazed at seeing in the flesh one of those Black men they only saw on television or in movies.

Whereas such amazement at my exotic looks and skin color was somewhat amusing, other reactions to me were downright infuriating, as in this incident on my last night in the country.

I had visited a night club in Beijing on my first night in China with a small group of French and German men. We were all dressed casually and we were admitted with the usual courtesy given to the club’s patrons.

On my last night in China, I returned to the club alone and dressed as casually as I had been the first time. This time, however, the club’s security guards refused to let me in. Frustrated, I demanded to know why.

Eventually, a Brazilian promoter who was fluent in Mandarin spoke to the security guards, and he told me that they assumed I was a local drug dealer, as there were Nigerian drug dealers in the area.

Apparently, because I am Black I must have been one of them. I was infuriated.

Fortunately, as my anger began to peak, a promoter from the nightclub who was originally from Hong Kong spoke to the security guards and brokered a deal on my behalf: If I changed from wearing camouflage pants and a sweater into more formal attire, I could come into the nightclub. I obliged him.

I had to leave the country the next morning, no other venues in the part of Beijing that I was in were open, and I wanted to go out one last time, or I would have probably decided to go elsewhere.

Such an open prejudiced attitude toward Blacks was clearly evident during the Coronavirus outbreak, so much so that in an April 13th health alert the U.S. Consulate General warned about discrimination against African Americans in Guangzhou, China.

“As part of this campaign, police ordered bars and restaurants not to serve clients who appear to be of African origin. Moreover, local officials launched a round of mandatory tests for COVID-19, followed by mandatory self-quarantine, for anyone with “African contacts”, regardless of recent travel history or previous quarantine completion

African-Americans have also reported that some businesses and hotels refuse to do business with them,” the bulletin read, according to The Washington Post.

The consulate general said it “advises African-Americans or those who believe Chinese officials may suspect them of having contact with nationals of African countries to avoid the Guangzhou metropolitan area until further notice.”

Even though all human beings are fundamentally the same, blackness has been discriminated against for centuries through meticulously-constructed systems and knee-jerk reactions.

Xenophobia and unfounded fears of other human beings go back not only to Vedic India but to much earlier eras in human history.

Hunter-gatherers in Africa and Mesopotamia knew such fears of others when the world was truly dangerous for the average human being and the tribe when resources were truly scarce, and when interacting with a foreign tribe of humans or wild animals could mean sudden death.

Such non-specific fears of others may be hardwired into our genetic material, alongside compassion, understanding, altruism, and fairness. However, discrimination against specific races is learned through family systems, media, and other forms of socialization, as far as I can tell.

Most racists are oblivious to the aforementioned systems and spontaneous reflexes that render them racists; they simply believe their prejudices to be objective truths, without considering where their beliefs came from.

This is clearly problematic not only in terms of philosophy and rational thought, not only based on what modern science has taught us about cognitive biases but also for those individuals who suffer from anti-Black racism and other forms of prejudice.

An unforgettable dialogue between two characters in Quentin Tarantino’s World War II epic “Inglorious Bastards” illustrates most dramatically the irrationality that informs ethno-racial prejudice.

This eye-opening conversation begins with Colonel Hans “The Jew Hunter” Landa’s statement to Perrier LaPadite that squirrels and rats are fundamentally the same, and yet most people hate rats and not squirrels.

The exchange between the two men then goes on to probe the illogic of racial hostility through a Socratic dialogue:

Colonel Hans “The Jew Hunter” Landa: “Yet they’re both rodents, are they not? And except for the tail they even rather look alike, don’t they?”

Perrier LaPadite: “It’s an interesting thought, Herr Colonel.”

Colonel Hans “The Jew Hunter” Landa: “Ah! However interesting as the thought may be it makes not one bit of difference to how you feel. If a rat were to walk in here right now as I’m talking, would you greet it with a saucer of your delicious milk?”

Perrier LaPadite: “Probably not.”

Colonel Hans “The Jew Hunter” Landa: “I didn’t think so. You don’t like them. You don’t really know why you don’t like them; all you know is you find them repulsive. Has a rat ever done anything to you to create this animosity you feel toward them?”

Perrier LaPadite: “Rats spread disease. They bite people.”

Colonel Hans “The Jew Hunter” Landa: “Rats were the cause of the bubonic plague, but that’s some time ago. I propose to you any disease a rat could spread a squirrel could equally carry. Would you agree?”

Perrier LaPadite: “Oui.”

Colonel Hans “The Jew Hunter” Landa: “Yet I assume you don’t share the same animosity with squirrels that you do with rats, do you?”

Perrier LaPadite: “Non.”

Obviously, the racial prejudices of the Nazis, in their full inglorious illogic, caused incalculable harm to millions of people, especially Jewish people, and continue to be problematic for many.

The same irrationality underpins the perception of Blacks around the world. To millions of people blackness is associated with inferiority and danger, and yet most who harbor such anti-Black prejudices cannot articulate why they do.

When I watched the video of George Floyd being killed by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, as his former colleagues complacently looked away, it occurred to me that George Floyd’s cries for his deceased mother were indicative of the fact that he felt as vulnerable in his last moments as he did as a small child.

His dying cries thus represented the precarious position of Black people and other people of color in North America and elsewhere, who are more often than not powerless in the face of the insidious and pervasive forces of systemic racism.

Like all people of color, Blacks often wonder how it came to be that White Europeans and their descendants acquired such power over others. In search of answers, I discovered a while ago Jared Diamond’s 1997 best-selling book, “Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies” (previously titled “Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years”).

In this insightful and eminently readable work Diamond attempts to explain why Eurasian and North African civilizations have survived and

conquered others, while arguing against the idea that Eurasian hegemony is due to any form of Eurasian intellectual, moral, or inherent genetic superiority over a variety of other cultures.

The prologue opens with an account of Diamond’s conversation with Yali, a Black man who is a New Guinean politician. The conversation turned to the obvious differences in power and technology between Yali’s people and the Europeans who dominated the land for 200 years, differences that neither of them considered due to any genetic superiority of Europeans.

Yali asked, using the local term “cargo” for inventions and manufactured goods, “Why is it that you White people developed so much cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but we Black people had little cargo of our own?”

The book’s title is a reference to the means by which farm-based societies conquered populations of other areas and maintained dominance, despite sometimes being vastly outnumbered — superior weapons provided immediate military superiority (guns); Eurasian diseases weakened and reduced local populations, especially in relation to aboriginals, who had no immunity, making it easier to maintain control over them (germs); and durable means of transport (steel) enabled imperialism.

Diamond argues geographic, climatic, and environmental characteristics that favored the early development of stable agricultural societies ultimately led to immunity to diseases endemic in agricultural animals and to the development of powerful, organized states capable of dominating others.

So, it is plausible that guns, germs, and steel contributed to the present state of Black people and other people of color in North America, and that poor luck and timing are also some of the many variables that have led to the death and suffering of millions of Black people.

Notwithstanding the hand dealt by history, Blacks individually and collectively continue to exert themselves and to strive for achievement and autonomy.

Since I was a child, and thanks to good fortune, and the leadership and wisdom of my parents, I was provided with many opportunities to express myself creatively, to educate myself in various ways, to be educated in various ways, and to engage in personal development.

Thus I was lucky to become a student of the Claude Watson School of The Arts in Toronto; I was fortunate to be in the gifted program at McKee Public School in Toronto after I temporarily left Claude Watson, and it was a blessing to be involved in numerous extracurricular activities throughout my studies, including but not limited to my time as the Arts Council Representative on the student council at Earl Haig Secondary School — the school that houses the Claude Watson Arts program and the largest high school in Canada at the time. Unfortunately, I had very few Black classmates.

My propensity for overachievement still exists today. It is certainly a by-product of my family system and a personal commitment to excellence, but it is as well a reaction to society’s perception of Black people.

My efforts to excel in my professional spheres stem in the conscious or unconscious wish to dispel the negative images of Black people in the media and the low expectations so many in society have about Blacks. I am sure that Oprah Winfrey and Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs have felt the same way for most of their lives.

Overachievement has seemed to be the only means of obtaining a measure of recognition, from my perspective. Since I was a kid, I have convinced myself to believe that I can never perform at an “average” or “good” level in any undertaking, for doing so would confirm to some others that I was as inferior as their unprocessed prejudices led them to assume I was.

As a Black male who has been subjected to different forms of neurosis and racism, I came to believe that I have to hit a home run on every pitch, or it is not worth playing baseball.

I am no stranger to the old notion of tokenism and exception. At my high school graduation ceremony, for example, I was the only Black male to attend a reputable university that was considered to be a Canadian equivalent of an Ivy League university.

I have felt like the token black guy in many situations in the past, and especially while attending The University of Western Ontario, which is now known as Western University, a predominantly white school.

Today, I feel like the token Black guy whether it be while working with a predominantly White Fortune 500 company, holding a gig in a predominantly White startup, or being in a hatha yoga class with mostly White women.

For a while, I found it a challenge to transcend the notion that Black people are inherently flawed. I often wondered why, if such shame-based propaganda was not true, there were so few Black people around me in environments that were stereotypically associated with academic, social, intellectual, or economic achievement.

Why were mannerisms and conventions that were stereotypically Black frowned upon in such environments? Why was most of the history that I learned in school based on the achievements and narratives of White males? Why were Black people mostly exempt from conventional forms of wealth creation, as far as I could tell? And why was it that I was more often than not surrounded by many Black people in environments associated with pop culture, sports and entertainment, such as the sports teams that I once played on, and the popular music, entertainment, and sports companies that I have worked with as a professional photographer, director, and producer?

The vast majority of the media that I consumed as a kid led me to believe that to gain attention by the masses as a Black person, one had to be entertaining, or a criminal, or both.

The many facets of systemic racism that have been at work since Vedic India have led Black people to harbor a measure of self-hatred as individuals and to be wary of one another, while simultaneously being subject to hatred from many other groups and organizations, including but not limited to certain law enforcement officers, certain bankers, and so on.

Throughout modern history, the covert or overt belief that blackness must be isolated and destroyed, both within and outside of black communities, has been held by too many ordinary and influential people. And the consequences have been devastating, as recent riots and demonstrations make clear.

Police brutality seems to be the most publicized and overt expression of anti-Black racism in the 20th and 21st centuries. It is nothing new; racism is as American as apple pie.

Aries Spears of “Mad TV” fame told me in May of 2020 that America is “the Babe Ruth of racism”. George Floyd’s death was the straw that broke the camel’s back, albeit temporarily, and the COVID-19 pandemic and recent economic recession have been major aggravating factors.

Anti-Black racism is often enforced in the media through the coverage of crimes involving Black people.

Given that many law enforcement officers have been consuming such media diligently since childhood, and since some officers have unwisely acted on their prejudices, there has developed a long-standing distrust between Black communities and the police, which is unfortunate, as there are plenty of good and great cops around the world.

The Ontario Human Rights Commission studied seven years of data surrounding interactions between police and Black residents in Toronto.

The Commission’s report concluded that Black residents face disproportionate discrimination and violence at the hands of the police. While Black residents make up less than 10% of the city’s population, they accounted for 61% of all cases where police used deadly force and 70% of police shootings that resulted in death.

In Toronto, Black citizens are twenty times more likely to be shot dead by police than other citizens, as outlined in the report, and such statistics are far more startling in a number of major American cities.

Closely related to these incidents of police violence is the practice of racial profiling, the coded attribution of certain traits and behaviors to people of a certain ethnic or racial background. Blacks are thus perceived as potential offenders and therefore inherently dangerous.

Although many Canadians would object, racism then undoubtedly exists in Canada, in all industires, and throughout all poltiical parties.

In a CBC article entitled “Canadian cultural institutions have silenced Black voices for years. Can we write a new chapter?”, my colleague Amanda Parris states that “days after the premiers of both Quebec and Ontario denied and downplayed the existence of systemic racism in Canada, social media platforms were flooded with narratives that painted a very different picture. In a wave that echoes of the #MeToo movement, Black folks from across the country are sharing numerous personal testimonies that call out specific businesses, institutions and organizations for their anti-Black practices. These stories are moving and enraging, affirming and disappointing, inspiring and devastating. And they’ve powerfully undermined and challenged many organizations’ public statements of solidarity to the struggle.”

Historically, the first systematic expression of widely-spread racism in Canada is the genocide of millions of aboriginals — a genocide that began as early as the 1600s, following the settlement of French explorers in modern-day Canada.

It may be argued that such genocide continues today with the treatment of the First Nations and their constrained lives on the reservations.

As for anti-Black racism in this country, there were thousands of Black slaves in Canada, and the erasure of Africville, an African-Canadian village located just north of Halifax and founded in the mid-18th century, remains one of its most egregious historic examples.

The City of Halifax demolished the once-prosperous seaside community in the 1960s, an act motivated by racism for which the mayor of the Halifax Regional Municipality apologized in 2010.

One of the most perverse effects of racism is the fostering of self-hatred among many a Black individual and of conflict within Black communities. Such self-hatred stems from the many factors described in this article.

In the United States, for example, from 2000 to 2015, the mean African-American homicide-victimization rate, adjusted for age, was 20.1 per 100,000. That’s more than three times the Hispanic rate of 6.4 (despite disadvantages compared to those of Blacks) and over seven times the average White rate of 2.7.

Moreover, from 1976 to 2005, 94% of the killers of Black murder victims were other African Americans.

In 2014, African Americans constituted 2.3 million, or 34%, of the total 6.8 million correctional population. African Americans are incarcerated at more than 5 times the rate of Whites.

Black people are dramatically over-represented in Canada’s prison system, making up 8.6% of the federal prison population, despite the fact they make up only 3% of Canada’s total population. What is more, between 2003 and 2013, the incarceration rate among Black people increased by nearly 90%.

Being of African descent in North America, and more specifically, being a Black male in North America often means being a stranger to oneself, a threat to other Black people, a menace to law enforcement, and a danger to society at large.

To be a Black male in North America often means being public enemy number one and consequently labeled a criminal at worst or a source of entertainment and laughter at best.

The irony of the self-perpetuating cycle of anti-Black racism in the United States is that there is no American history without African Americans, and modern pop culture, politics, science, and many important industries would be less robust and innovative without Black people.

The U.S.A. was literally and figuratively built by African slaves, and the American social, cultural, political, and economic landscape is inconceivable without the contributions of African American artists, intellectuals, politicians, activists, athletes, and ordinary Black folks.

Racist oppression in its various forms in North America has led to many episodic revolts. The 1992 Los Angeles riots, sometimes called the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, were a series of civil disturbances in Los Angeles County in April and May 1992.

The unrest began in South Central Los Angeles on April 29, after a trial jury acquitted four officers of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) for use of excessive force in the arrest and beating of Rodney King, which had been videotaped and widely viewed in TV broadcasts.

The rioting took place in several areas in the Los Angeles metropolitan area, as thousands of people took to the streets over a six-day period following the announcement of the verdict.

Widespread looting, assault, arson, and murder occurred during these uprisings, which local police forces had difficulty to control due to lack of personnel and resources against the sheer number of rioters.

The situation in the Los Angeles area was only resolved and ended after the California Army National Guard, the United States military, and several federal law enforcement agencies were deployed to assist local authorities.

By the time the riots ended, 63 people had been killed, 2,383 people had been injured, more than 12,000 had been arrested, and estimates of property damage were well over $1 billion.

History seems to repeat itself. The Los Angeles riots did not bring an end to the many forms of discrimination against African Americans.

The current riots in all fifty American states and around the world triggered as the earlier ones by a callous example of anti-Black racism are the latest pushback from the victims of oppression.

The marches and protests of 2020 will go down in history as the most widespread protests against discrimination towards Black people since the civil rights movement. There comes a point when Black people and their allies simply resolve that enough is enough.

As broached earlier, racism, both overt and covert, often hurts the most at the economic and public health levels, and as such, a recent Toronto Life article bears the title “When you’re Black, you’re at greater risk of everything that sucks”.

According to the Financial Times, in 2018, the median household income for a Black family in America was $41,361, having grown 3.4% over the previous decade, according to the latest US Census Bureau data. This compared with a median income of $70,642 for non-Hispanic White families in 2018, which had grown 8.8% since the 2008 crisis.

According to a report published in February by the Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think-tank, the net worth of a typical African American

family in 2016 was $17,150, while the equivalent figure for a White family was 10 times greater at $171,000. Such figures led the authors of the report to conclude that American society “does not afford equality of opportunity to all its citizens”, and contrary to popular belief, many African American families were enslaved through indebted servitude until the 1960s, according to VICE’s research.

In regards to the health of African Americans, CNN recently reported that “the current pandemic has also laid bare the inequities in the nation’s health care system. One reason why Black Americans have been hit harder is that they are less likely to have health insurance.

This holds true even among the employed. Black workers are 60% more likely to be uninsured than White workers, the Economic Policy Institute found.

Along with a lack of coverage, Black Americans have higher rates of chronic illnesses, including diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity. All these conditions contribute to making the Coronavirus pandemic all the more deadly for Blacks than for non-Hispanic Whites, who account for more than 60% of the population, but only about 53% of the deaths from the virus.”

Besides the health concerns elicited by their situation in society, health concerns that include many mental illnesses, Blacks in the United States must also contend with exclusion in the employment market and low pay, especially in the tech sector.

Major technology companies and technology startups in Silicon Valley are arguably the most influential companies in existence, and they shape human consciousness more so than all other organizations today.

Unfortunately, people of African descent make very few contributions to such companies based on the number of Black employees hired through such organizations, other organizations have similar hiring practices, and this is not due to a lack of ingenuity amongst Black people.

According to Wired, “Google reported this year that just 5.5% of its 2019 hires were Black, compared with 4.8% the year before. (The company did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)

Facebook has almost doubled its number of black employees since 2014, but the number still sits at 3.8%.”

Casual police brutality against Blacks and the systemic racism described in this article have been written about and protested at length by many thought leaders in the United States and elsewhere.

The Black experience has been spoken and written about in great detail by such leaders. Their words echo through the hallways of history and permeate the collective consciousness of humanity today, although such words often remain unheeded.

Martin Luther King Jr. once stated that “There comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe nor political nor popular, but he must take it because his conscience tells him it is right.” The great Tupac Shakur confessed with a mixture of resignation: “I see no changes, wake up in the morning and I ask myself, is life worth living, should I blast myself? I’m tired of bein’ poor and even worse I’m black. My stomach hurts, so I’m lookin’ for a purse to snatch.” The great James Baldwin articulated that “to be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” Malcom X, for his part, concluded that “there can be no Black-White unity until there is first some Black unity. There can be no workers’ solidarity until there is first some racial solidarity. We cannot think of uniting with others, until after we have first united among ourselves. We cannot think of being acceptable to others until we have first proven acceptable to ourselves. One can’t unite bananas with scattered leaves.” Barack Obama once asked, “Can we see in each other a common humanity, a shared dignity, and recognize how our different experiences have shaped us?” Diva Nina Simone wisely stated “I’ll tell you what freedom is to me: no fear. I mean really, no fear!” Another great singer, Lauryn Hill, told us that “I had to confront my fears and master my every demonic thought about inferiority, insecurity, or the fear of being black, young, and gifted in this Western culture.” And my favorite comedian, Dave Chappelle has articulated that “Things like racism are institutionalized. You might not know any bigots. You feel like “well I don’t hate Black people so I’m not a racist,” but you benefit from racism. Just by the merit, the color of your skin. The opportunities that you have, you’re privileged in ways that you might not even realize because you haven’t been deprived of certain things. We need to talk about these things in order for them to change.”

The combined words and actions of these brilliant minds and of organizations like the Black Panthers, the Nation of Islam, the NAACP, and many more, have done much to break some of the chains of systemic racism that still exist today.

One of the largest and most peaceful acts of defiance and solidarity amongst Black people was the Million Men March, a large gathering of African-American men in Washington, D.C., on October 16, 1995.

Called by Louis Farrakhan, it was held on and around the National Mall. The National African American Leadership Summit, a leading group of civil rights activists and the Nation of Islam working with scores of civil rights organizations, including many local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People formed the Million Men March Organizing Committee.

A couple of decades after the Million Men March, Black Lives Matter (BLM) has entered the forefront of popular culture as an international human rights movement.

Originating in the African American community, BLM’s mission is to campaign against violence and systemic racism towards Black people.

The organization regularly holds protests against police killings of Blacks people and addresses broader issues such as racial profiling, police brutality, and racial inequality in the United States criminal justice system.

Countless Black Lives Matter marches have taken place internationally in response to the recent killing of George Floyd, demanding justice for Floyd, and the prosecution of all four former police officers responsible for his death.

As a result of BLM’s work and the social media outrage that has stemmed from George Floyd’s death, countless governmental policies, social norms, and companies have changed drastically and arguably for the better in a few weeks.

There is a common misconception that Black Lives Matters promotes the denigration of a variety of races and ethnic groups, or suggests that the lives of non-Black individuals do not matter.

Instead, Black Lives Matter simply promotes the fact that Black people are often viewed as less than human, and that systemic racism against them ought to be brought to the forefront of world issues. In fact, anti-Black racism is now considered a public health crisis in Toronto.

In North America especially, many Blacks are made to feel they do not matter; and BLM simply proclaims otherwise.

In 2013, the BLM movement began with the use of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on social media after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of African-American teen Trayvon Martin in February 2012, and the hashtag has become wildly popular over the course of the last two weeks since race once again has come to the foreground as an urgent societal issue.

On Saturday, May 30, 2020, thousands of Torontonians took to the streets, demanding justice for Regis Korchinski-Paquet, three days after the 29-year-old woman fell to her death from a High Park highrise, in an incident that is now under investigation by Ontario’s civilian police watchdog.

As previously mentioned, my photographs of the march, which accompany this article, document a protest that was organized by a group called Not Another Black Life, in association with Black Lives Matter.

The protest began at Christie Pits Park and culminated hours later outside Toronto police headquarters on College Street.

The marches and protests around the world have been successful inasmuch as they have raised awareness about anti-Black racism around the world, a lot of financial and social capital has been allocated to address anti-black racism globally, at least far more than was allocated a few months ago.

The events of the last few weeks have changed things for the better, but it will take far more than marches, protests, and hashtags to resolve the systemic issues described that Black people face in the long-term, as such challenges have been self-perpetuating for centuries.

During the first week of June 2020, #blackouttuesday and posting a plain black square via social media became a sign of solidarity amongst millions of people around the world.

However, it was ineffective in many ways, because many of those who posted a black square did so as a form of disingenuous conformity or virtue signaling, and many of the #blackouttuesday posts lacked in vital information pertaining to systemic anti-Black racism.

Virtue signaling is the action or practice of publicly expressing opinions or sentiments intended to demonstrate one’s good character or the moral correctness of one’s position on a particular issue.

Also, because of the algorithmic nature of social media, social media users are essentially presented with content that is in alignment with their social media activities, and consequently with their values and interests.

So, an individual that was consuming a great deal of racist rhetoric leading up to #blackouttuesday probably did not learn much about the many downsides of racism or the hardships that Black people face in North America.

The trauma of the transatlantic slave trade cannot be encapsulated in a hashtag, and it will take more than a hashtag to address systemic racism.

The lamentable fact is that many of the companies that participated in #blackouttuesday will not hire more Black employees or contractors in the near future, nor will many of the individuals that participated in the social media phenomenon become less racist in the near future.

That said, from my limited vantage point, I believe that it is time to do some things that have not been done to address systemic anti-Black racism, especially in the United States, a country that Canada undoubtedly views as a big brother.

Firstly, all parties involved, from government agencies to law enforcement, educational institutions, banks, housing projects, and many other actors, can benefit from meditation.

Various forms of meditation lead to metacognition, which is the capacity to think about one’s thoughts and to question and process one’s thoughts, which may well be the first step towards challenging racism.

Moreover, meditation is a scientifically-proven method of addressing reactivity, violent impulses, and the stress that is experienced by the oppressed and oppressors alike. At the very least, those that are victimized by different forms of meditation can mitigate their trauma, including their transgenerational trauma by meditating regularly.

I know from my experiences, from my work as an ambassador for Calm — the most downloaded meditation and sleep app in the world, and from my work as the Art Director for Operation Prefrontal Cortex — a Julien “Director X” Lutz co-founded program harnessing the power of mindfulness and meditation to help reduce the incidents of gun and mass violence in Toronto, that meditation has many benefits that can contribute to anti-racism and far less violent acts amongst and towards Black people and people of color.

For example, research from the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC) suggests that meditators’ acceptance of their own emotions (through mindfulness) is the key to self-control.

Furthermore, researchers from the Benson-Henry Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital cause what is known as “the relaxation response”, which is the opposite of the “fight-flight-freeze” response. Their research suggests that meditation alleviates anxiety and also has positive effects on heart rate variability.

Also, Duke University researchers have found that mindfulness meditation brings about various positive psychological effects, including increased subjective wellbeing, reduced psychological symptoms, and emotional reactivity, and improved behavioral regulation.

But meditation is not a panacea. There must be concrete actions to redress economic exclusion. People of African descent with the proper qualifications and work ethic must be hired more often, at higher rates, especially through the most influential companies in the world, including but not limited to the Silicon Valley startups and tech companies.

Recently, Black Entertainment Television co-founder Robert Johnson told CNBC that the U.S. government should provide $14 trillion of reparations for slavery to help reduce racial inequality.

According to Johnson, the wealth divide and police brutality against Blacks are at the heart of protests against police brutality and the death of George Floyd. “Now is the time to go big” to keep America from dividing into two separate and unequal societies, Johnson said on Squawk Box.

“Wealth transfer is what’s needed,” Johnson added. “Think about this. Since 200-plus-years or so of slavery, labor taken with no compensation, is a wealth transfer. Denial of access to education, which is a primary driver of accumulation of income and wealth, is a wealth transfer.”

I believe that such reparations should be made to all people of African descent in North America and other centers of colonialism.

Also, all individuals and educational institutions in North America and elsewhere can benefit from studying and promoting literature that clearly describes the true nature and implications of colonialism, the transatlantic slave trade, anti-Black racism, and the many amazing, influential, and advanced African civilizations that existed prior to the transatlantic slave trade, including but certainly not limited to ancient Egypt.

An instructive reading list would include such books as “The Autobiography of Malcolm X”; “Notes of a Native Son” by James Baldwin; “The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution” by C.L.R. James; “Roots: Saga of an American Family” by Alex Haley; “Incidents in the Life Of A Slave Girl” by Harriet Ann Jacobs; and “Song of Solomon” by Toni Morrison. North Americans especially must learn how North America was built.

Some of the solutions to anti-Black racism may also be found in geopolitics, in the construction of a new Black nation that projects an image of wealth and strength on the global stage.

In this respect, my father believes that a politically, economically, intellectually, and socially powerful Black state must be established, a state strong enough to hold America and other countries accountable for the abhorrent treatment of its Black citizens, much like China calls America and other countries to account when Chinese people are treated poorly overseas, whether they were born in China or not.

At least some, if not all, the solutions briefly described here must be implemented if systematic anti-Black racism is to be dismantled or at least reduced.

It has been a long road, but there is a ray of hope at the end of the journey as long as there are people and organizations still at the barricades for justice and equality.

Those people of good faith in Canada, and especially in Toronto who wish to help fight the good fight may offer their support to such organizations as Stolen From Africa, Manifesto Community Projects, The Remix Project, Operation Prefrontal Cortex, Across Boundaries, Afri-Can Foodbasket, Black CAP TO, Black Legal Action Centre, Black Toronto Community Support, and Black Lives Matter Toronto.

A popular link on American organizations that can be supported is available at blacklivesmatters.carrd.co, and a pre-recording of an anti-systemic racism panel that I was on earlier this summer via Manifesto Community Projects and The Government of Canada may be of interest.

This article describes major human rights and public health issues, and each and every one of us, as long as we are fated to live together, is duty-bound to contribute to the collective effort to build a more just and harmonious society.

Black lives matter because, in many situations, institutions, and systems, they are most at risk of isolation, exclusion, insecurity, anxiety, depression, and death, and such facts do not undermine the inherent value of all human beings.