Welcome to our special section, Thrive on Campus, devoted to covering the urgent issue of mental health among college and university students from all angles. If you are a college student, we invite you to apply to be an Editor-at-Large, or to simply contribute (please tag your pieces ThriveOnCampus). We welcome faculty, clinicians, and graduates to contribute as well. Read more here.

If you’re in business, you have a moral duty to be involved in politics — especially during this time. If you look at important business figures in history, it becomes clear that well-intentioned businesspeople have changed the arch of politics for the better. And so can you.

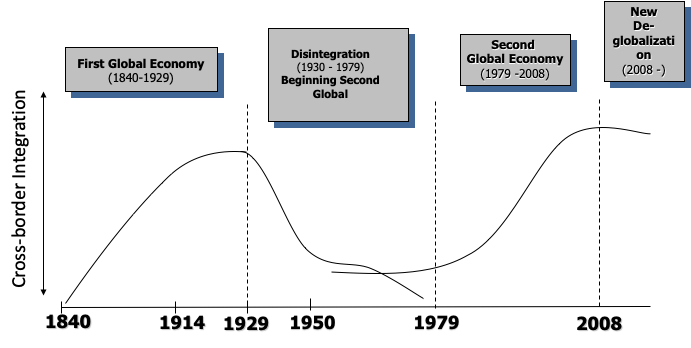

A study of the waves of globalization and de-globalization allows us to view this question through the lens of changing economic and political contexts and how that impacts the inevitability of the lack of separation of business and politics. At a high level, globalization waves reward high performance people and clusters. During periods of high globalization, the economic “winners” amass such influence that their involvement in politics becomes inevitable as “economic statesmen.” And during periods of de-globalization, state involvement to correct for the economic inequality, leads to greater need for businesses to align with governments in order to gain a competitive edge. This leads to a cycle whereby the intermingling of business and politics is inevitable regardless of globalization waves.

With the rise of the first global economy, nation states began to emerge. In these new nation states, political connections became a prerequisite for economic success and this led to global capitalism becoming built on the symbiotic relationship between economic and political actors. This is demonstrated by the consistent trend across global businesses that arose during that era, from Siemens to the Japanese industrial giants. Their leaders built and maintained close connections with political actors in order to amass wealth, and one can argue they wouldn’t have been able to achieve this without these relationships. I would hypothesize that the need for this alignment between aspiring entrepreneurs and political actors could be traced back to a time when power was concentrated with undemocratic “monarchs” (or their equivalents in a colonial context) that necessitated being a part of their circle to have access to any economic success.

In the case of Yataro of Mitsubishi, he was able to keep his independence from the government, subverting colonialism’s restrictions on Japanese-style government support for local entrepreneurs. However, he ended up making his fortune as part of Japan’s war machine, which also greatly harmed the Taiwanese and Koreans. He used nationalism as a rouse and as the north star to motivate his workforce. He leveraged political ideologies to drive productivity, and ultimately, profit. He was unable to maintain a separation between politics and business.

The need to leverage politics to derive profit became a core building block of global capitalism. The industrial revolution that global capitalism birthed saw a great divergence with a few winners amassing great wealth. Despite the mounting concerns around the de-legitimization of capitalist ideals due to this great divergence, the scale of modern business placed economic winners in positions of incredible influence. And with influence, political involvement becomes unavoidable. The Modern Corporation (1932) highlighted how concentration of power in the economic field led to the law of corporations essentially being considered a potential constitutional law for the new economic state and brought about this concept of business practice increasingly assuming the role of economic statesmanship. The extent of economic statesmen’s impact was huge — in both productive and unproductive ways.

Zemurray of the United Fruit Company was an example of someone who touted his role as an economic statesman to overthrow governments in United Fruits’ favor. For example, he used his leverage in the U.S. to convince the U.S. government to support Guatemalan rebel forces as this constituted “a part of American national interest,’’ despite the US mandate dictating that American companies shouldn’t “enjoy immunities and privileges abroad that would make for political instability or social injustice in other countries.” He is an example of a very troubling economic statesman. Zemurray’s deeply unproductive actions have led to the long-lasting marginalization of people and the crippling of a country.

Bajaj, the industrialist behind Gandhi’s legacy in India, typifies the positive role of the economic statesman in driving political change. He wore the motto of “simple living, high thinking” in his practices and used his privilege to create shared value. His use of business-minded passive resistance was incredibly powerful. He asserted Indians’ right to make salt by defying the law that proscribed such an act. Salt was used by everyone and this act became a reminder of the injustices of British colonialism in India.

In my view, the difference between Zemurray and Bajaj was intent. Intent is at the core of whether business’ contribution to politics is productive or not. In 1949, Dean David spoke about how one of the tenants of responsible business leadership was a “willingness to participate constructively in the broader affairs of the community and nation.” I would highlight the word constructive, which points to the importance of economic statesmanship being well-intentioned. This was contested by a number of scholars, like Thomas Levitt and Milton Friedman who argued that “the social responsibility of business is to increase profits” — in my opinion, this view that places profit over everything else is deeply problematic.

Walking through time, we saw a trend of de-globalization and a time of increasing state intervention. The high government intervention saw (almost everywhere) reduction in wealth/income inequality, which may have restricted the influence of the previous “winners.” However, with governments being everywhere, it became vital for business leaders to align with state actors in order for them to provide support and protection, especially in strategic industries and turbulent regions. Then, again, as we neared the trough of cross-border integration in the 1970s, governments began again to be seen as the problem, and markets as the solution, which strengthened the role of economic statesmen. The intrinsic link between politics and business is clear, but its desirability is still up for debate.

As the Theory of the Firm and Agency Costs (1976) took form. It highlights how we regularly make the error of thinking about organizations as if they were persons with motivations and intentions.

“The firm is not an individual. It is a legal fiction which serves as a focus for a complex process in which the conflicting objectives of individuals (some of which may “represent” other organizations) are brought into equilibrium within a framework of contractual relations.”

In my view, for one to be considered a productive economic statesman or —woman they must be able to take a broad-minded view beyond their individual or their business’ interest. They need to be able to decouple their company’s interests from the system that supports it and this goes against the modern capitalism. Capitalism in its current form has misaligned incentives and prioritizes fiduciary duty.

The case of Rupert Murdoch, for example, highlights how an inability to delineate between corporate and personal interests in engaging in political dimensions can be deeply unproductive. For instance, Murdoch’s personal ambition to disrupt the elite was an underlying current throughout his career, but in doing so, he aligned with many political leaders that he thought would benefit the unit economics of his journalism, biasing individual voice and threatening democracy.

We have now explored how business and politics are fundamentally intertwined, and how this can be good news if the actors are well-intentioned. With intention being specifically tied to their integrity with respect to maintaining a broad-minded view beyond their individual or their business’ interest. There remains an open question around whether it is morally objectionable for today’s business leaders to maintain their fiduciary duties as they take on a role as an economic statesman?

In my view, the incentive structures and expectations established by traditional capitalism has cultivated virtues that encourage problematic attitudes that prioritize profits over people. However, I have hope. We’re seeing a clear shift in discussion towards recognizing that we have a “crucial, even life-saving role to play” as business leaders and the recent note by Larry Fink of BlackRock highlighting the role business plays in the community provides a view that this balance might shift in favor of people. And with that, incentives should be better aligned for business leaders to engage in politics to bring about productive and positive change.

Subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

More Thrive Global on Campus:

What Campus Mental Health Centers Are Doing to Keep Up With Student Need

If You’re a Student Who’s Struggling With Mental Health, These 7 Tips Will Help

The Hidden Stress of RAs in the Student Mental Health Crisis