Talk to Nobel Prize-winning structural biologist and Stanford Medicine Professor Michael Levitt, and he’ll tell you that, though no one could have foreseen the precise outcome, the basic science research he did in the 1980s indirectly led to a $40 billion a year industry in anti-cancer drugs. He is convinced: “Spending on basic science pays off.”

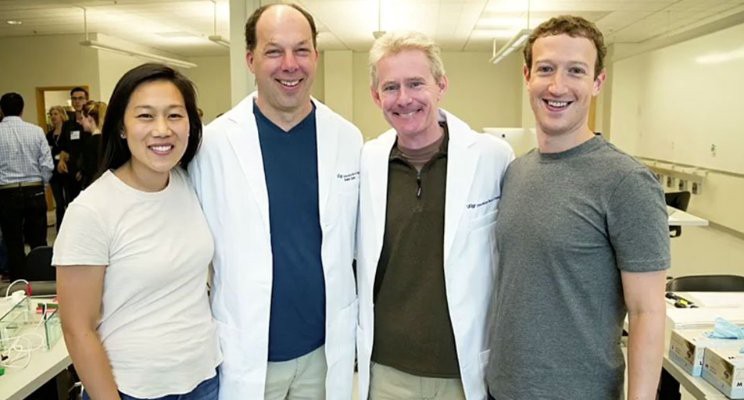

So am I — and so are Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan, who today announced their decision to give $600 million to form a new, independent research organization called the “Chan Zuckerberg Biohub.” A collaboration between Stanford, UC San Francisco, and UC Berkeley, the Biohub will engage in basic research projects with the aim of curing all diseases by the end of the century.

Fundamental research is our most constant and reliable engine of discovery.

Fundamental research is our most constant and reliable engine of discovery. Generation after generation, it unleashes the imagination of a fresh crop of young scientists, like those toiling away in our labs as I write. It helps them create the new knowledge that improves our lives.

When we look past the potential practical applications of basic research, we are free to see what we weren’t even looking for. This is true both in medicine and well beyond it: When John Bardeen first made a transistor in 1947, it was a “lab curiosity” without practical use. No one foresaw its revolutionary significance for electronic devices and computers (even Bardeen thought it might be useful in hearing aids, but wasn’t sure beyond that). The World Wide Web was invented as a way for particle physicists to communicate. GPS derived from atomic clocks developed to test Einstein’s theory of relativity.

We can never know what will prompt a life-changing discovery. The trick is to create the best environment for mental serendipity.

We can never know what will prompt a life-changing discovery. The trick is to create the best environment for mental serendipity. Stanford Medicine has always believed in giving the best and brightest faculty and students significant time and freedom to pursue their best and brightest ideas. We work hard to unshackle their imagination from limits otherwise imposed on it (by conservative and contracting federal funding, for example, requiring short-term and pre-determined results) so they can turn insight into innovation.

Within the last few years, Stanford Medicine has awarded $4 million to basic scientists through 46 competitive innovation grants to support highly creative projects, like the molecular and developmental origins of human facial diversity and methods for identifying patients who might be harmed by treatments for heart disease. Already these grants have led to tangible outcomes: a new mobile health app for migraines, practical advances in creating new antibodies, and a potential new cancer drug that has moved into Phase I clinical trials.

At the same time, we have raised $9 million through philanthropy to cover the first four years of training for our PhD students in the biosciences — the extraordinary young minds who will uncover fundamental mysteries of biology, develop new technologies, and advance the proactive treatment of disease. The future of Precision Health — our vision for more predictive, preventive healthcare — lies in their hands, in their labs.

We face so many challenges today: sustainable energy and the environment, water security, an urbanizing world and its great possibilities and problems. We are dealing with intensely complex issues. They will require innovative solutions that we have yet to fathom. None of us can know the precise route with certainty, but basic science will help steer us there. So join me in cheering on today’s scientists to think, and bet, big. In the end, it will pay off not just for them, but for all of us.

Originally published at medium.com