I often find helpful moments come to me this way: Some image or idea rattles around in my brain for a while, coming from who knows where. If I only vaguely pay attention to it, other things start happening. I stumble upon a related story or book or a quote until I get the point, as I did this morning: Oh, it’s time to attend to joy—even in the midst of a pandemic.

Here’s how that unfolded this week:

First, I kept thinking of the story about the poet Ruth Stone that Elizabeth Gilbert shares in her 2009 TED talk: When Stone was growing up in rural Virginia and working in the fields, Gilbert says, “she would feel and hear a poem coming at her over the landscape.”

“She knew that she had only one thing to do at that point, and that was to, in her words, ‘run like hell,’” Gilbert says. “And she would run like hell to the house and she would be getting chased by this poem, and the whole deal was that she had to get to a piece of paper and a pencil fast enough so that when it thundered through her, she could collect it and grab it on the page.”

Sometimes, Stone would miss the poem—and sometimes, she would almost miss it. Gilbert describes those moments this way: “So, she’s running to the house and she’s looking for the paper and the poem passes through her, and she grabs a pencil just as it’s going through her, and then she said, it was like she would reach out with her other hand and she would catch it. She would catch the poem by its tail, and she would pull it backwards into her body as she was transcribing on the page. And in these instances, the poem would come up on the page perfect and intact but backwards, from the last word to the first.”

Why did that delightful—or, depending on your point of view, slightly kooky—story keep coming to me all of a sudden? I had no idea.

Then, I had a dream that I was writing in my study when my neighbor took his hose and playfully sprayed the window near my desk, apparently not seeing it was open and getting water on my computer. In waking life, I would have been upset. In my dream, it felt playful, like a childhood memory of running through a sprinkler.

Finally, this morning, I started a new book and, on page two, came upon this quote from Bertrand Russell: “One of the symptoms of an approaching nervous breakdown is the belief that one’s work is terribly important.”

And suddenly, I got it. It is time to be more playful and childlike and to stop taking myself so seriously, even in this serious time. It is time to make room for joy: that state of being that is different from happiness—more lasting and compassionate, and able to be found in the midst of suffering and adversity.

The Book of Joy

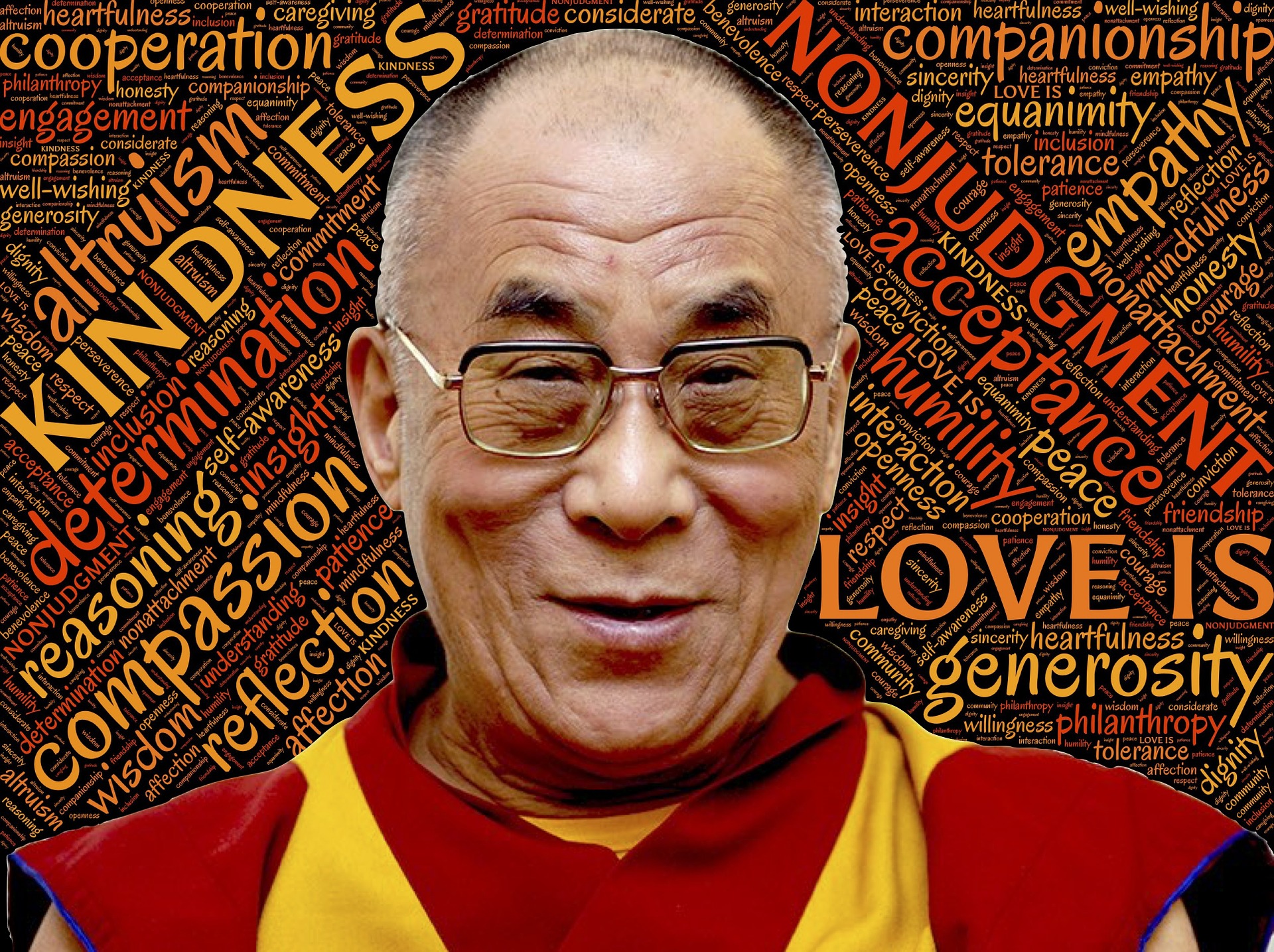

I pulled down my copy of The Book of Joy, a dialogue between the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, both Nobel Peace Prize winners, who journalist Douglas Adams describe this way:

“The Archbishop has never claimed sainthood and the Dalai Lama considers himself a simple monk. They offer us the reflection of real lives filled with pain and turmoil in the midst of which they have been able to discover a level of peace, of courage, of joy that we can aspire to in our own lives.”

He adds: “Their joy is clearly not easy or superficial but one burnished by the fire of adversity, oppression, and struggle.”

Might that be something we have burnished in us while going through the fires of this extraordinary pandemic moment? I imagine it is possible if we run like hell to catch it, grabbing it by the tail if necessary.

As for how? The Book of Joydescribes eight pillars of joy: perspective, humility, humor, acceptance, forgiveness, gratitude, compassion and generosity. It also concludes with 20-odd Joy Practices. Those all seem things worth dipping into and reflecting on now. But if you don’t have time, this observation from the Dalai Lama might help:

As soon as I wake up, he says, “I remember Buddha’s teaching: the importance of kindness and compassion, wishing something good for others, or at least to reduce their suffering. Then I remember that everything is interrelated, the teaching of interdependence. So, then I set my intention for the day: that this day should be meaningful. Meaningful means if possible, serve and help others. If not possible, then at least not to harm others. That’s a meaningful day.”