When my niece started high school, she had a big decision to make. She was a talented soccer, softball, and basketball player, and when she wasn’t playing sports, she was busy with a fast-growing business making and selling “slime.”

But she couldn’t do everything.

Each activity took an increasing amount of time, and she was curious to try new activities—robotics, and maybe the school newspaper. And what about all the possibilities she didn’t know about yet?

Her parents wondered how they could help her. They’d read about the paradox of choice—that having too many options can paralyze decision making—and thought they should limit the number of activities under consideration. But the options were so different. They didn’t know how to cut them down, and there were some she hadn’t considered yet that she might like a lot.

Making good decisions involves choice architecture: structuring the presentation of options in a way that leads to a satisfying result. For example, New York City presents eighth graders with more than 700 different high schools in a large book, and asks them to rank their top 12. It’s easy for families to feel lost and kids to end up in a school that’s a bad match. Experiments that cut the options to 30—eliminating schools that are too far away, for example—helped students make better choices.

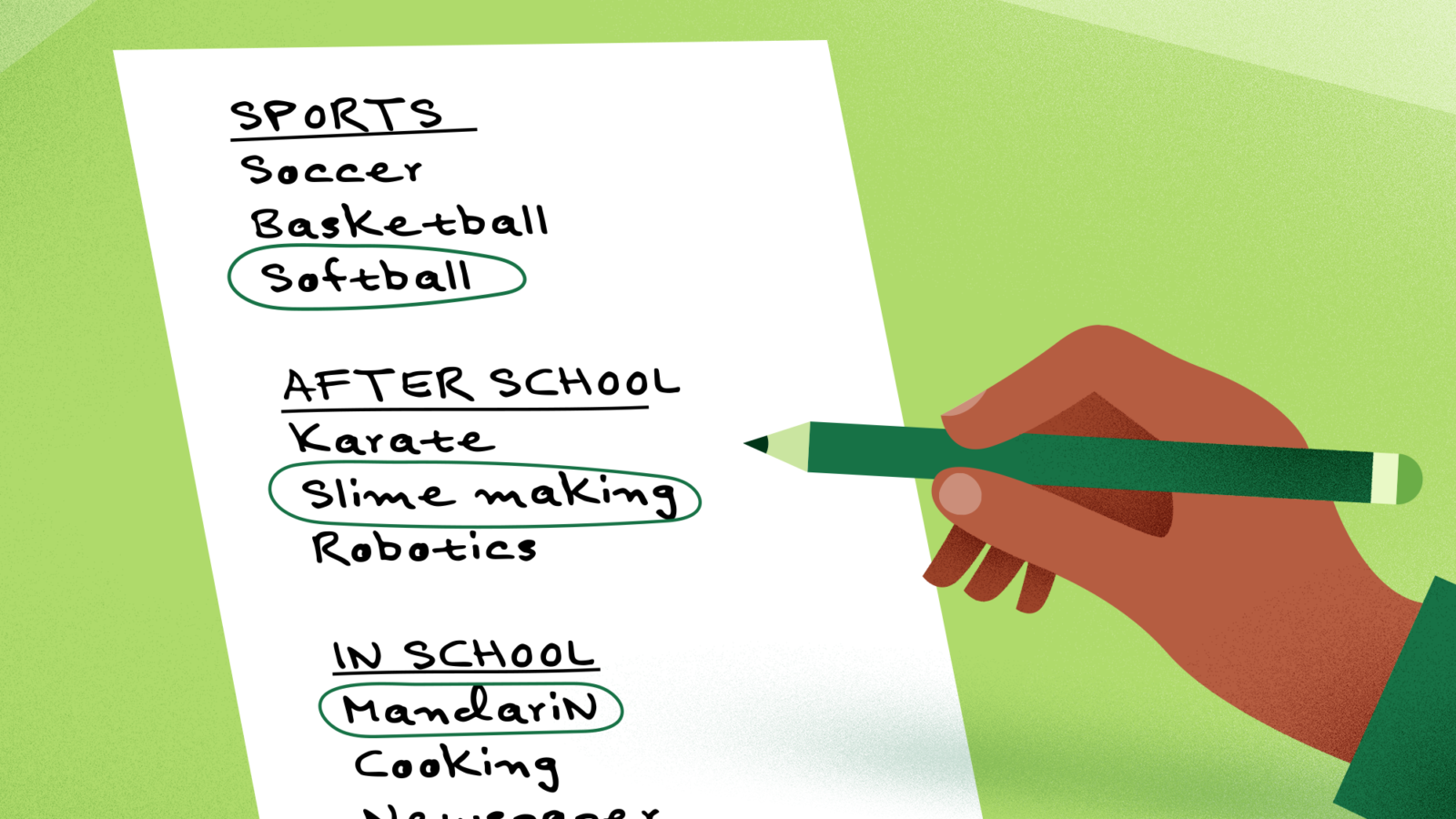

As for my niece, her parents wanted to present ample options without overwhelming her, so they eliminated ones they knew she wouldn’t like. But they left some choices, such as taking Mandarin, where they didn’t know what her reaction would be. They also structured the choices into categories like sports, after-school clubs, and in-school challenges. She could make a choice within each category or decide which category was more important, and that made the process easier.

Don’t make all the choices for the young people in your life. Exploration leads to expansion.

Do help young people make wise choices. For instance, you can present an otherwise overwhelming list of extracurricular activities in a certain order. You can direct attention to features you think are worth prioritizing. In other words, as a choice architect, you can make daunting decisions feel doable.

With curiosity and gratitude,

Eric

Eric Johnson, the Norman Eig Chair of Business and Director of the Center for Decision Sciences at Columbia University, is the author of The Elements of Choice: Why the Way We Decide Matters.