Hopkins, my high school in New Haven, Conn., at one time required each senior to give a speech before morning assembly.

That requirement had vanished by the time I arrived at the school in 7th grade in 1977.

But it reminds me of the lost art of public speaking, which is tied to other lost arts, wit, charisma, eloquence, persuasiveness in argument and storytelling, to say nothing of originality.

Not one of these characteristics can be measured quantitatively.

We are living at a time when Harvard is being sued over its admission policies that, according to the plaintiffs, may be biased against Asian-Americans, who often do well on standardized tests but are perceived by the school not to rate as highly on personality, or what one might call “leadership qualities.”

We are also living at a time when our nation’s chief executive, who views himself as embodying the qualities of a fearless leader, lives by a code of bluster, bullshit and outright lies.

Our solipsist-in-chief serves as an atrocious role model to young people, not only because he lies, but also because he may be “functionally illiterate,” to use a phrase from James Mattis’ new book, Call Sign Chaos.

If memory serves, Harvey Keitel, the actor, told John Avlon, then of the Daily Beast, that Trump has “no poetry” to him.

If only Trump would read. But it’s too late for that.

To read well takes years, as I have written before. The same can be said of other forms of communication. Very few people speak or write eloquently.

Getting back to my days in high school, although the requirement of giving a speech before morning assembly had ended, I addressed morning assembly more than a few times when I was at Hopkins.

When I was a senior, I gave a speech on Peter Lorre, the character actor from the 1940s, whom I described as the “quintessential mad man.”

And in my capacity as editor-in-chief of the high school paper, I made a number of announcements when I was a senior.

But the speech that stands out to me was the one I gave in 1981, when I was in 11th grade.

Mrs. Maria Dawidoff, my adviser and English teacher, who was the head of the assembly committee, knew how much I loved old movies and asked me if I would like to give a talk on one of my favorite actors.

I told her that I would love to do so, and I gave my speech on Errol Flynn in late October of 1981.

As I walked to the stage in my street clothes, I carried a crossbow, which I leaned against the lectern.

Then I stepped to the right of the podium and proceeded to remove my street clothes only to reveal that I was wearing a green cloak and tunic and green tights, Sherwood Forest garb that I had borrowed from a friend.

He had dressed up as Robin Hood the year before at Halloween or what we at Hopkins called Pumpkin Bowl.

“Why am I dressed in the guise of Robin Hood today of all days?” I began my speech, alluding to the Passover liturgy. “No, it’s not because I delight in being the center of your ridicule.”

Just about everyone in the auditorium, 600 students and faculty, cracked up.

“It’s because I wish to pay homage to Errol Flynn, who was buried 22 years ago today.”

I then regaled everyone at assembly with amusing anecdotes about Flynn, whose movies, such as The Adventures of Robin Hood, I had loved since I began watching them when I was in first grade.

I had watched them on Channel 5, then an independent station in New York, now the Fox flagship, beginning in late 1971, after we bought our first color TV, a Sony, on sale at Caldor’s.

Our old TV, a black and white Panasonic, got only a few channels, ABC, CBS, NBC and PBS.

But starting in late 1971, with the benefit of our new TV, I became a devotee of the classic Warner Brothers playhouse. I was introduced to these films from the 1930s and ‘40s by my father, who was trying to get me interested in something, anything, given that I was severely depressed and that I had stopped reading, or at least stopped enjoying reading.

What my father did not know, and what I did not realize either, since I was dissociating, was that I had been traumatized the prior school year by the sadistic actions of my kindergarten teacher.

I have described in a previous article how she sent me to the “dunce corner,” when I, the only Jewish kid in the class, missed school for the Jewish High Holidays in 1970, at the time that I turned five years old.

My kindergarten teacher refused to let me use my left-hand, my dominant one, and she repeatedly ignored, humiliated or punished me with trips to the “dunce corner” for much of the rest of that school year.

Her goal was to destroy my spirit, to wreak havoc with my brain and soul, but, as evil as she was, she could not prevent me from identifying the letters correctly when she finally was forced to call upon me late in the school year in the spring of 1971.

While my kindergarten teacher failed in her desire to hold me back, she did succeed in damaging the architecture of my brain.

After that school year, I seemed to get little pleasure from anything, and I had trouble with my dexterity, with fine motor skills, as I still do to this day.

That was when my dad, in a stroke of genius, brought into my life the imaginative world of Errol Flynn, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, John Garfield and Edward G. Robinson.

It would be hard to convey how much I gravitated to and relished watching those old Warner Brothers movies, fast-paced gangster pictures and swashbucklers, Westerns and war films, many of them set on the Lower East Side, and all of them featuring snappy dialogue.

One cannot quantify the love that I had for those films, a love, that, like all true devotion, was unlimited.

As I have written before, Flynn and the other stars, as well as supporting players, like Alan Hale, Guinn “Big Boy” Williams and Frank McHugh, and actresses like Olivia De Havilland and Ann Sheridan, became my pals, my repertory company of friends, whom I saw several times every weekend and sometimes during the week.

I mention all this because, while I stopped reading for pleasure for many, many years, I still had an active imagination.

When I started 7th grade at Hopkins in 1977, Mrs. Toni Giamatti, my first adviser and English teacher at the school, asked our class on the first day, “Who is Truman Capote?”

You can imagine how I responded.

“He’s an actor. He was in Murder by Death,” I said of a comedic film, a spoof on the murder/mystery genre, that had come out in 1976.

Mrs. Giamatti nodded. “That’s true,” she said. “But does anyone know anything else about him?”

As I was still suffering from PTSD, from the repercussions of my kindergarten teacher’s sadism, something I would not tame for about 40 years, I had done next to no reading outside of elementary school.

I had read only the sports section of the New Haven Register, and I had only started doing that in 5th grade.

Later, when I was in 8th grade, we began getting the New York Times delivered to our home, and I would start to read Red Smith and other sports writers of the Gray Lady.

I limited my reading to sports articles because those articles alone seemed welcoming to me at a cognitive or spiritual level, given my trauma and depression.

But in 7th grade, I was going to have to start reading literature, and Mrs. Giamatti had us begin with Jug of Silver, a short story by Capote.

After class that first day, Mrs. Giamatti asked me about my interest in movies.

I mentioned that I was aware that, besides Murder by Death, Capote had been in Beat the Devil, a Humphrey Bogart picture.

Mrs. Giamatti was quite familiar with the latter film as well.

In fact, she told me that Capote had been one of the writers of the screenplay of that film, a point that meant little to me at the time.

I also did not know but would soon learn that Mrs. Giamatti had been an actress, who had studied at the Yale School of Drama.

Her classmates included Frank Langella, who, around the time I was in 7th grade, was starring as Dracula at the old Shakespeare theater in Stratford, Conn. She also talked about Dick Cavett, then a major talk-show host, who was one of her friends and who had acted in plays while he was an undergraduate at Yale.

I had many wonderful teachers at Hopkins, including Mrs. Dawidoff, but Mrs. Giamatti was different because she turned her English classrooms at least partly into workshops in theater.

All of us would read passages aloud in class, whether those passages came from plays, like Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, which we read when I was in 7th grade, or from short stories, like Capote’s Jug of Silver.

Mrs. Giamatti understood, more than any other English teacher I had at Hopkins, the critical importance of voice, of hearing the way language sounds on the page, if one is to become a writer.

She also had an appreciation for wit, for good cheer and for playfulness, not unlike Rosalind, the heroine of Shakespeare’s As You Like It.

Needless to say, one cannot measure these attributes of Rosalind. They are sublime, like the love that Antony has for Cleopatra, who famously asks her beau to quantify their romance.

“If it be love indeed, then tell me how much?” says Cleopatra.

To which Antony responds, “There’s beggary in the love that can be reckoned.”

“I’ll set a bourn how far to be beloved,” she says.

“Then must thou needs find out new heaven, new earth.”

As I wrote last year, the Zohar, the most authoritative text of Jewish mysticism, indicates that metrics mean little on this planet, except insofar as they pertain to holy matters, such as resting on the seventh day, the Sabbath, or spending 40 years in the desert, which shows endurance and dedication to God.

Not surprisingly, we are not supposed to read the Zohar until we are 40, when it is thought, according to Jewish tradition, that we may have attained some wisdom.

It strikes me as being quite on point that, as I wrote earlier, it has taken me some 40 years to process and heal from the trauma that was inflicted on me when I was in kindergarten.

All of which is to say that you are not going to find or create a new heaven, or a new earth, with a reliance on metrics, particularly not those of a pedestrian or fake nature, such as alleged crowd sizes, TV ratings or SAT scores.

I have been thinking about all of this in light of the recent cover story in the New York Times Magazine that delved into the lawsuit that has been filed against Harvard.

The piece discussed affirmative action, the concept of reverse discrimination against Asian-Americans, the relative importance of test scores, and diversity.

It also called into question what constitutes merit in a college applicant.

Should students be evaluated primarily by SAT scores and grades? What role should be played by athletic accomplishments? What about legacy issues?

And what exactly does Harvard mean by an applicant’s “personal rating”?

Based on the piece, written by Jay Caspian Kang, the plaintiffs who have brought the lawsuit believe that Harvard has intentionally limited admissions to otherwise qualified Asian-Americans because they do not score well on the so-called “personal rating.”

According to the article, the argument of the plaintiffs seems to be that the Harvard admissions department views many Asian-Americans as lacking the personality to interact with other students, to contribute fully to the university, and to exhibit the kind of leadership skills that will reflect well on Harvard years from now, after the students graduate and enter the work force.

While it is true that Harvard, in the early part of the last century, did institute a well-known quota system against Jews, the college has denied that it now has a quota system against Asian-American applicants.

Lost in all of this discussion about test scores versus personality, or “leadership qualities,” is whether the applicant possesses some of the other intangibles I wrote about earlier, such as imagination, eloquence, wit, character and originality, attributes that definitely cannot be measured in any quantitative sense.

They are not unlike the love that I had and still have for those old Warner Brothers movies, to which I was introduced by my father when I was a depressed child.

When I was at Hopkins, I won the Harvard Book Prize as a junior, and the citation referred to my imagination and my memory as gifts.

Given the severity of the trauma I endured in kindergarten, I did not always test so well on reading comprehension when I was taking standardized tests, a multilayered irony given that I had been reading well prior to kindergarten and that I would later become a proofreader at L.A. Weekly in 1997.

The latter event occurred when I was 31 and was just a few months after I got out of the USC psych ward, where I had been hospitalized at the time of my first psychotic break.

Long before my psychotic episodes and suicidal ideation, back when I was in high school and suffering from PTSD and depression, there were a couple of kids who had a higher grade point average than I did.

That is not surprising to me, since, as per the Zohar, I understood at an intuitive level that class rank or SAT scores, while relevant, do not define a human being.

Moreover, I was never driven by any need to say that I was first or best at anything.

All I really wanted was to be happy, a far more elusive goal.

As a senior at Hopkins, I applied to and was accepted early at Yale.

At the time I applied, I was ranked 5th in my class, as I recall; I would graduate in a tie for 8th at Hopkins.

Then I headed off to Yale, where I majored in English, and, where, among other subjects, I studied Chaucer.

One of my classmates in Professor George Fayen’s class was Paul Giamatti, who would later become an award-winning actor.

He is a son of the late Toni and Bart Giamatti, who became president of Yale in 1978 when I was in eighth grade.

Like everyone else in my Chaucer class, I had to recite the opening 18 lines of “The Canterbury Tales,” which I rejoiced in doing for Professor Fayen and which I can still do to this day.

The Middle English diphthongs remain seared in my auditory cortex, or, as Professor Fayen once said, “genetically embedded in your DNA.”

I can still hear Chaucer’s poetry, which sounds a bit like Swedish, as it wends its way through recesses in my hippocampus and onto my tongue.

And I can still hear Mrs. Giamatti telling my bildungsroman class during my senior year at Hopkins that I should be a writer.

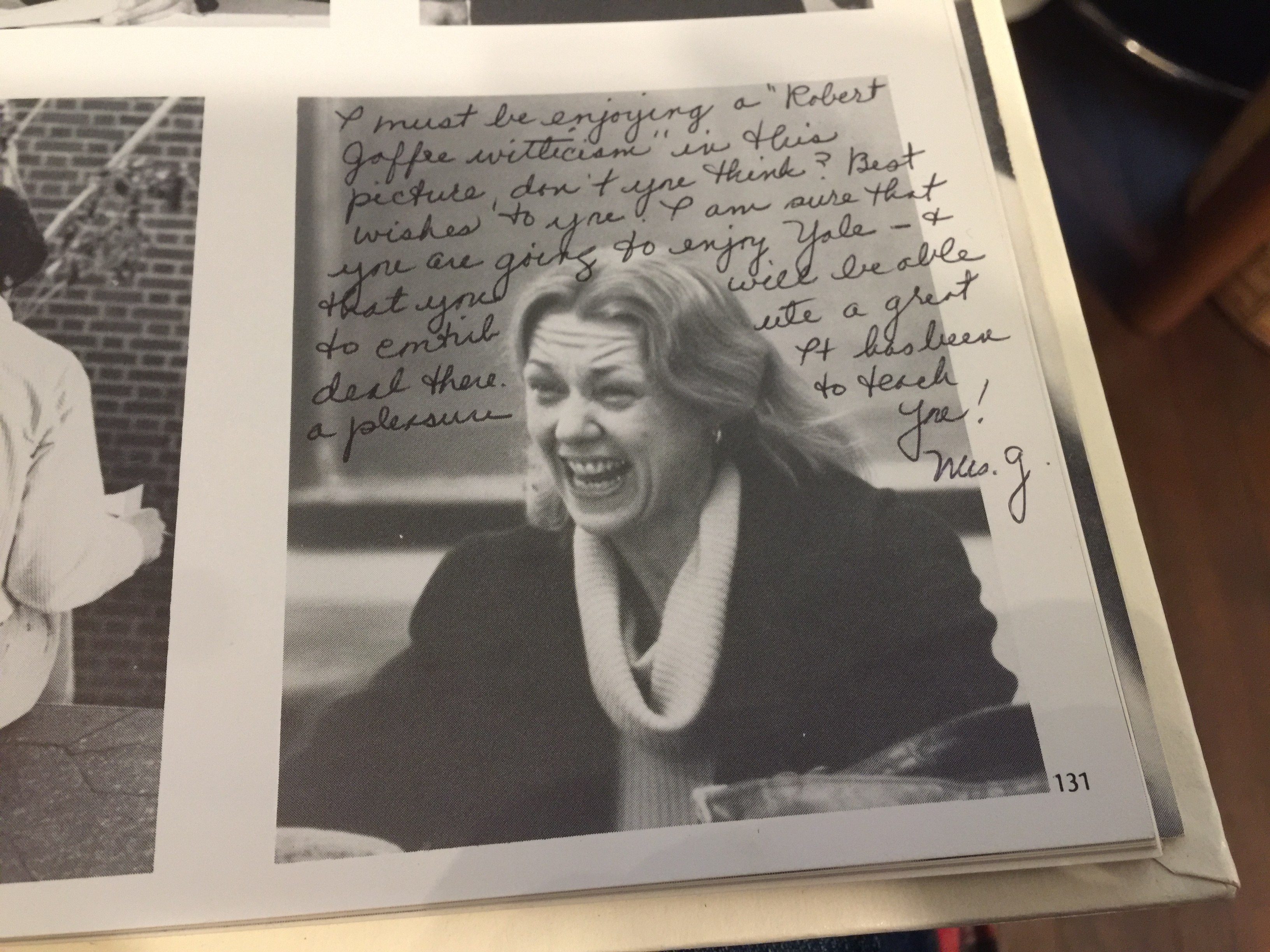

Mrs. Giamatti signed my high school yearbook in 1983. She inscribed her note next to a delightful photo of her, where she is beaming.

She wrote in my yearbook, “I must be enjoying a ‘Robert Jaffee witticism’ in this picture, don’t you think?”

I don’t know how the highly publicized lawsuit against Harvard will turn out.

I can understand the argument of the plaintiffs as well as the argument of the Harvard admissions department.

Of course, as Hamlet would say, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

And there are more ways of assessing the merits of a human being than test scores or so-called leadership qualities.

We writers tend to be idiosyncratic and not prone to leading in any traditional way.