In mid-February, I took a trip to New York City. One of my closest friends and I flew in from opposite ends of Canada and met up early in the morning at the Chelsea Market, where we stood in line to get bagels at Amy’s and then sat drinking coffee in a communal seating area. Over the weekend, we hopped packed subways out to Brooklyn, browsed books elbow-to-elbow at the Strand, crammed into the Comedy Cellar to watch John Mulaney do a set, ate off the same plates at Prune, and bunked in the same bed at night in our midtown hotel.

That carefree, crowded world has, of course, vanished. New York is under siege. As we grieve for a city we love, my friend, a doctor, is back in Vancouver, tending to coronavirus patients. I am back at home in Toronto, covering the pandemic for my newsroom. And everyone, everywhere, is sheltering in place.

The world of two months ago is gone. In its place is a strange, surreal existence in which we are all almost always at home, alone, afraid. Our relationships relegated to screens. Our routines paused, our lives on hold. Our futures uncertain.

This is not the first time I’ve faced such a reckoning.

Four years ago, I was a current affairs journalist when I started having chest pains at my desk. My doctor ordered me to take time off to undergo a cardiac workup. For months, as I awaited tests, I could barely leave my apartment. Alone, fearful for my health, with far too much time on my hands and far too little money, I was forced to rethink everything.

Now, in the wake of the coronavirus, everybody else is doing the same.

I can tell you this: In my many months convalescing on the couch, I began to see how insane the modern world had gotten. How stressful it was to work such long, hectic, harried hours. How crazy it was to forgo sleep, solitude, social life – all those things that make life worth living – and still be struggling to make ends meet. How alienating it was to live in a fractured, polarized society.

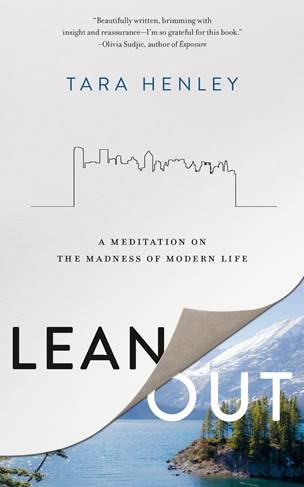

It eventually became clear that I was not suffering from a cardiac condition, but anxiety. I wound up taking a few years off to research and write a book that took me around the globe and introduced me to many people who were similarly disillusioned, from “radical homemakers” in upstate New York and prison reform advocates in Los Angeles, to rappers in Scotland and men who lived without money in rural Ireland.

The answers they came up with were pretty simple. Friendship, family, food. Nature. Thrift. Community. And perhaps most importantly, the idea that we are all connected, and that our salvation lies in acknowledging that fact.

The coronavirus is now taking such conclusions mainstream. We are terrified of the virus and panicked about finances, it’s true. But we are also experiencing a slower, less-pressured schedule, many of us for the first time in our lives.

As cars disappear from the roads, nature rushes back in. The air clears and fills with birdsong. We take morning strolls, relearning what it feels like to be part of a neighbourhood – even from a waving distance.

Many of us find ourselves with both the time and the inclination to place long calls to friends. To cook actual dinners. To rediscover home. To read, to sleep, to think deeply. To walk.

Overnight, our complex modern world has been simplified.

It seemed impossible, given the accelerated pace of capitalism and technology, that we would ever return to a simpler time. And yet here we are. Under horrific circumstances, it’s true. But nevertheless, here.

There are other shifts taking place, too. After decades of assault on the idea of public institutions, we are all now recognizing their critical role. In the midst of this pandemic, we need governments to close businesses and schools and parks. We need public health officials to analyze data. We need the media to report on it.

The notion of the greater good is resurfacing. Ordinary workers are now our heroes: grocery store clerks and take-out delivery drivers, nurses and cleaners and transit operators – people who are risking their lives to answer society’s call.

Globalization is in retreat. Hopping planes to exotic locales now feels reckless, and far-flung supply chains unwise. We are refocusing our gaze back on our own country, our own city, and in many cases our own block.

Greed is abhorrent. Price-gauging, hoarding, evicting low-income tenants, billionaires Instagramming their yachts – previously business-as-usual in late stage capitalism – has been deemed largely unacceptable. Individualism itself is under fire.

Meanwhile, economic and racial inequality has become glaringly obvious. And the toll it takes on everyone’s physical and mental health is finally being recognized. As Heather McGhee, senior fellow at the Demos think tank, said in a recent TED Talk, we are starting to see that “our fates are linked,” and that “an injury to one is an injury to all.”

In Canada, we are seeing bold action at every level of society. The government has introduced what amounts to a universal basic income. “Care mongering” movements are on the rise, as citizens step forward to get groceries for seniors and check up on acquaintances self-isolating. Health care and grocery chain and non-profit executives are covering shifts on the frontlines. Donations to food banks are pouring in.

In this pandemic, as in my years of leaning out, we are glimpsing what life might be like if we organized our society differently. Confined to our homes, with modern life all but shut down, possibilities open up. The impossible suddenly seems possible.

We must seize this pause, this season of leaning out, to build a more just and equitable world. We are all in this together, and we must start thinking – and acting – from that place.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.