I don’t like following recipes. It’s something about being told what to do. Look, I know that I’m being told what to do by a trained professional who has tested countless variations of a recipe and offers me the best and easiest option. Nah, not for me. I like to look at the pictures, get inspiration, half-follow the recipe, then wing it. Do I really need to get out my electric mixer (I’m already picturing the subsequent additional cleaning required)? Must I separate the yolk from the white? Come on, they’re both going into the bowl later anyway? That sort of thing. I own just a few cookbooks, mostly gifts.

So I surprised myself when I, in the midst of Corona isolation time, ordered a whole bunch of cookbooks online and couldn’t wait for them to arrive. I was inspired by the Netflix series, Ugly Delicious, in which American chef and leader of the Momofuku restaurant empire, David Chang, hangs out with other chefs and celebrities and speaks, heartfully and honestly and without pretension, about foods that he loves and knows not enough about. I love the show and love Chang and think his restaurants sound amazing, which is also odd since I’ve never eaten in any of them. I’m a big fan based on how good his food looks and sounds. Not tweezer-foam-abstract expressionism good-looking, but I want to dive headfirst into this bowl finger-licking good looking. It was after his episode on tacos that I clicked “place order” and the cookbooks winged their way towards me.

When they arrived, I did what I imagine few people associate with cookbooks. I read them. I read each one, cover to cover, pouring through as if they were novels. I’ve helped to write a cookbook (From the Alps to the Adriatic: JB’s Slovenia in 20 Ingredients which comes out with Skyhorse in 2021) and my wife translated one (Cook Eat Slovenia by Spela Vodovc) so I know a perhaps surprising statistic: some 80% of cookbook buyers do not use the recipes. They buy cookbooks for inspiration, to browse the pictures, because they’re fans of the author. Now, cookbooks sell well, always. My own publisher of illustrated books, Phaidon, may be famous for art history books like mine, but they make most of their money from their cookbook division. Turns out that most people buy cookbooks for everything but the recipes. But they buy cookbooks, nonetheless.

Which means that I’m in good company. Heck, the fact that I eventually got around to cooking from them, too, means I’m in the elite minority 20%!

The cookbooks I ordered included two David Chang offspring: Momofuku and Lucky Peach’s 101 Easy Asian Recipes. The latter was written by Chang’s business partner in the short-lived but wonderfully quirky Lucky Peach magazine, Peter Meehan, who is my new bro crush. Look, as a professional writer I know how hard it is to a) actually make a reader laugh, and b) write in interesting, fresh ways about food. Meehan does both. I literally laughed aloud many times while reading his short texts accompanying those Asian recipes. Then I read the text to my wife, with difficulty, as I kept cracking up. This is very hard to accomplish. Hat’s off to you, Mr. Meehan. For some reason, being at home, particularly in the Slovenian Alps (where Alpine food is readily available, but Asian is not), I get cravings for Korean food and tacos. Being able to cook at home what you crave and can’t get is sort of like a magic trick, and these cookbooks (particularly the Lucky Peach) allowed this, with wonderful élan and without worrying about authenticity, full of shortcuts when you can’t get ingredients. And I love shortcuts.

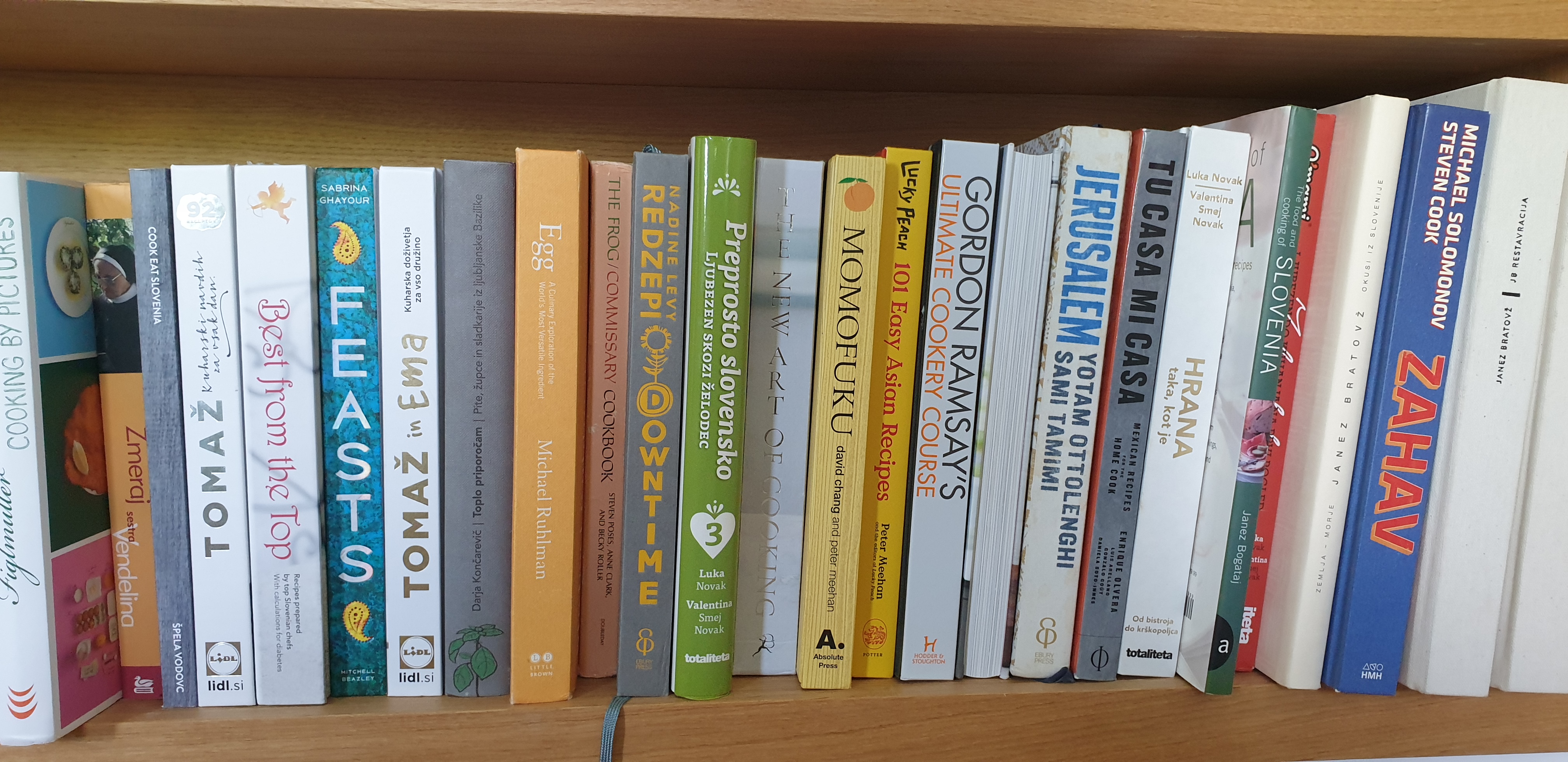

I also hit up Enrique Olvera’s Tu Casa Mi Casa (Mexican home cooking), published by Phaidon, Feasts by Sabrina Ghayour (various Arabic home cooking), Anita Sumer’s Sourdoughmania (sourdough baking from central Europe), Nadine Levy Redzepi’s Downtime (Danish home cooking) and Zahav by Michael Solomonov (Israeli home cooking). Zahav, in particular, did what I want cookbooks to do—tell me the story of the food, through the voice of the chef, to teach me about an exotic world through food that, if I’m feeling plucky, I can prepare myself. The recipes are the least of it.

The real story here is that there is a comfort in cooking, and therefore a comfort in cookbooks. We all love food and we love our families. During this time when we feel at risk and isolated, one of the best gifts we can offer our family is to cook them delicious things that perhaps take a bit more effort. Food is doubly precious now, because of the logistical complexities of grocery shopping, and the lack of options for eating out. Particularly during the first month of quarantine, in March, I tried not to leave the house at all, and was one of the many thousands poised at the stroke of midnight to log into a supermarket’s overburdened website when it reset itself to take more online delivery orders. I kept hitting refresh and thinking I got in, and I’d load up my virtual shopping cart, head for checkout—and then the website would freeze. It felt like I’d been through a battle and lost out. The websites have since gotten their acts together and now can take orders normally, but there is nothing more basic and visceral than taking measures to feed your family. And even in a first-world situation, with first-world level problems (I know that my complaint that “this darned online delivery website froze on me!” is like playing the world’s smallest violin), it can feel like a relative fight for your family’s wellbeing.

So my reaction, to my own surprise, has been to dive into cooking and actually following recipes. I try to do as much as I can with my kids. My five-year-old is into baking, so we’ve made walnut brownies from Nadine Levy Redzepi and sourdough bread from Anita Sumer. My seven-year-old wanted fried chicken, and we’ve tried Redzepi’s recipe, as well as one from Lucky Peach and from Momofuku. I made “mall chicken” from Lucky Peach because I miss the totally inauthentic General Tso’s Chicken of my Chinese takeout youth, which Slovenian Chinese restaurants do not make and have never heard of. I made lacquered whole roast chicken Lucky Peach style, then made their fried rice out of the leftover and made Enrique Olvera’s chicken soup out of the carcass—very satisfying to get three meals out of one chicken. And I’ve been repeatedly making a hybrid of Christina Tosi’s “crack pie” crossed with Redzepi’s chocolate chip cookie recipes that, well, someone should put in a cookbook.

But mostly I’ve found solace in providing food for my family and sharing time preparing it. That’s one of the best things we can focus on during this trying time together.