It takes 60+ days to create a new habit NOT 21 days

The 21-day habit myth began when a plastic surgeon in the 1950s, Dr. Maxwell Maltz, noticed that his patients seemed to acclimatize to their new faces after a minimum period of 21 days.

This observation was reported in his famous book, Psycho-Cybernetics, and promptly adopted by self-help guru’s who forgot to inform their followers that the word ‘minimum’ was meaningful.

This short time frame made the idea of habit-creation seem more achievable, inspiring and enticing.

Yes, you do gain traction over the first few days of starting a new habit, partly from the excitement that creating a new habit provides, as the brain naturally craves novelty. However, and it can take more than 60 days for a new neural pathway to become entrenched and become part of your daily life without expending a lot of effort.

There are a few reasons why the ’21-days’ habit myth doesn’t hold up to neuroscientific scrutiny.

In creating a new neural pathway you don’t simply ‘over-write’ the previous pathway. Instead, you’re creating a new one from scratch, while also using conscious effort not to use the habit you’re trying to leave in the past.

In addition, the old neural pathway, for example, snoozing in bed before getting up for work, versus getting up early to go to gym, may still ‘entice’ and derail your efforts, as it still exists.

You’re also likely to find yourself in similar situations to where you engaged in the habit you’re trying to replace with a new one, which makes creating a new habit more challenging.

Ask anyone who hasn’t smoked a cigarette for years what if feels like when they’re exposed to a similar situation where they once enjoyed this bad habit. They’ll tell you that it’s as if they stepped back in time to when they used to light up. Why? That neural pathway still exists and is activated in similar situations or contexts.

It’s therefore paramount to avoid situations where the neural pathway of an old habit can easily be activated, as this makes it much easier to succumb to that old habit. For example, pre-order a green tea from a new, but still convenient restaurant, if you’re trying to quit your early morning coffee.

So create a new cue by nudging yourself differently and practice your new habit in a different context to where an ‘old’ habit can reassert itself.

It’s easier to create new bad habits versus new good habits

Most bad habits, like overeating, sleeping in and drinking too much coffee support the release of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin. Most good habits don’t do so initially as they naturally produce less of a brain ‘high.’

Dopamine is known as the pleasure neurotransmitter and it’s released when we do anything that increases our chances of survival, which include eating and having sex. However, it’s also involved in our brains reward and motivation pathways. It’s therefore a very powerful neural messenger and needs to be harnessed to support habit change, formation and reinforcement and maintenance.

Serotonin is also a powerful messenger as its release leads to feelings of safety and security, which are also powerful and support our survival. Recent research suggests it also has an important role to play in habit creation.

In addition, some research suggests that eating carbohydrate rich and fatty foods stimulate the release of endogenous opioids (made internally), which lead to a feeling of calmness. This mechanism underpins why we reach for such foods when stressed.

Obviously, breaking the habit of eating these foods when we’re stressed is extra hard. It’s therefore important to reduce stress when we’re trying to make good habits ‘stick.’

The naturally higher rates of synthesis and release of such neurotransmitters, which occur from stimulants like caffeine, and drugs such as alcohol, as well as the ingestion of highly processed foods, make it hard for the brain to embrace activities and behaviors that naturally release less of them.

Using this knowledge, we need to reward ourselves with something that also releases dopamine and/or serotonin, albeit in lesser amounts, in conjunction with a new habit. For example, treat yourself to a massage every week, which releases both neurotransmitters, while you’re establishing your new habit, or find out how to make a delicious and healthy meal quickly at the end of every day. Or treat yourself to some organic, dark chocolate after your new, healthy lunch.

Apart from the routine of the new habit, monitoring your progress can also become a new routine at the end of the day. Establishing a routine helps habits ‘stick’ and it’s easier to create a habit when you engage in the new activity daily.

Well nourished brains are better able to create new habits versus malnourished brains

It is likely that four dietary-related factors act in combination to support habit creation and maintenance.

Firstly, a poorly nourished brain lacks energy and vital nutrients that are necessary for cognitive functioning. Optimal brain activity is underpinned by neurotransmitter synthesis that supports decision-making, self-discipline and memory formation, all of which support the creation and maintenance of new habits.

Secondly, as the day progresses, if the brain isn’t optimally nourished, it will become less and less efficient at making good decisions. This is called ‘decision-fatigue.’

Unfortunately, this is particularly problematic when trying to start a new way of eating. If you don’t know how to feed your brain optimally you will reach for comforting, habitual foods at the end of the day, because a tired and hungry brain is less able to make good decisions and tends to respond in knee-jerk, habitual ways.

Thirdly, blood glucose highs and lows lead to poor decision-making because the brain gives into cravings in an attempt to quickly gain blood glucose stability. The brain thus doesn’t have the resources to think optimally and stay disciplined while trying to establish and maintain new habits.

Finally, for a new habit to become established, the neurons involved need to form a new neural pathway. This process involves neuronal communication and the myelination of new connections between neurons. Both of these processes rely on specific nutrients to operate optimally.

Therefore, nourishing your brain is foundational for the creation of ‘sticky’ habits.

Pair a new habit with an already established, positive behavior

Some research suggests that coupling a new habit to an already established behavior or habit increases the odds of the new habit becoming entrenched. For example, if you wanted to do more exercise, you could walk and talk with your friend rather than sitting down for your weekly catch up. Such changes can lead to new habits, which become routines and lead to new, robust neural pathways.

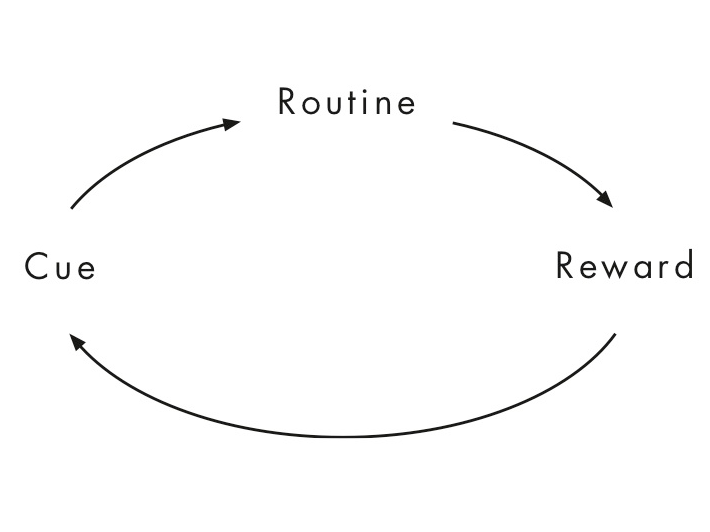

These ways of making habits ‘sticky’ lead to the creation of a ‘habit loop’ which includes creating a new cue, a new routine and adding a reward.

So, in summary:

• Stay disciplined for 60+ days AND use new cues AND contexts in relation to new habits to create a new routine

• Stimulate dopamine and serotonin release via healthy rewards for staying disciplined

• Support optimal habit ‘stickiness’ via ideal brain nourishment

• ‘Stick’ a new habit onto an already established positive behavior

Be creative and use these approaches to transform new resolutions into ‘sticky’ habits as we step into a new decade.

Please let me know if you’re planning on using other ways to make your new habits ‘sticky.’

You’re also invited to join Mindful Life Training’s Creating a Culture of Wellbeing Event in Melbourne and Sydney next month, to hear more about using the latest neuroscience in creating healthy habits and a total culture of well-being at work.

[This article was originally published on LinkedIn (Delia McCabe, PhD)

References

Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology and Behavior, 91(4), 449-458.

Adamo, A. M. (2014). Nutritional factors and aging in demyelinating diseases. Genes Nutr, 9(1), 360.

Bressan, R. A., & Crippa, J. A. (2005). The role of dopamine in reward and pleasure behaviour – review of data from preclinical research. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111(s427), 14-21.

Dolan, R. J., & Dayan, P. (2013). Goals and habits in the brain. Neuron, 80(2), 312-325.

Fogg, BJ. (2019). Tiny Habits. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, USA.

Gardner, B., Lally, P., & Wardle, J. (2012). Making health habitual: the psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 62(605), 664-666.

Kandiah, J., Yake, M., Jones, J., & Meyer, M. (2006). Stress influences appetite and comfort food preferences in college women. Nutrition Research, 26(3), 118-123.

Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998-1009.

McCabe, D. (2016) Feed Your Brain: 7 Steps to a Lighter, Brighter You! Exisle, Australia.

Neal, D. T., Wood, W., Wu, M., & Kurlander, D. (2011). The pull of the past: when do habits persist despite conflict with motives? Pers Soc Psychol Bull, 37(11), 1428-1437.

Nilsen, P., Gardner, B., & Brostrom, A. (2013). Accounting for the role of habit in lifestyle intervention research. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs, 12(1), 5-6.

Orquin, J. L., & Kurzban, R. (2016). A meta-analysis of blood glucose effects on human decision making. Psychol Bull, 142(5), 546-567.

Sanchez, C. L., Biskup, C. S., Herpertz, S., Gaber, T. J., Kuhn, C. M., Hood, S. H., & Zepf, F. D. (2015). The Role of Serotonin (5-HT) in Behavioral Control: Findings from Animal Research and Clinical Implications. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 18(10), pyv050-pyv050.

Spencer, S. J., Korosi, A., Laye, S., Shukitt-Hale, B., & Barrientos, R. M. (2017). Food for thought: how nutrition impacts cognition and emotion. NPJ Sci Food, 1, 7.

https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/1/2/18158989/habit-tracking-apps-new-years-resolutions