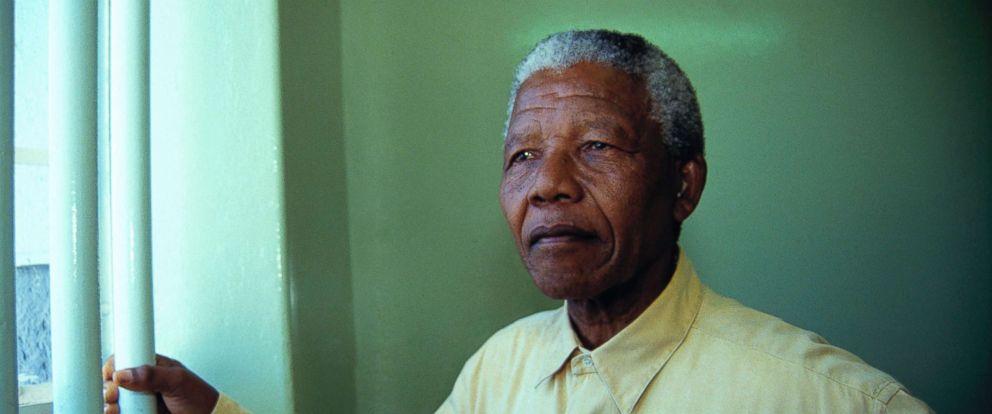

Throughout human history, we have celebrated figures notable for their brilliance and heroism. Winston Churchill. Nelson Mandela. Oprah Winfrey.

Nelson Mandela freed South Africa from apartheid in 1994, however a huge part of his legend started long before this feat. Mandela’s ability to adapt and remain strong in the face of incalculable odds and oppression laid the foundations of remarkable achievements. Mandela emerged from 27 years of incarceration having transformed from active revolutionary to international peacemaker. Whilst many would have sought revenge, he sought reconciliation, and showed remarkable strength of character, and awe-inspiring resilience.

Oprah Winfrey, born black and female in the US South, experienced a traumatic childhood marked by abuse, and yet she was able to rise to become one of the most influential figures in America. In 1993, Bill Clinton signed into law a national database of convicted child abusers. The bill was labeled the “Oprah Bill” because of her 1991 initiation of the National Child Protection Act.

Whilst we could link and define them by the many defining characteristics of leadership, one factor is shared by them all, and resides within all of us to varying degrees – remarkable resilience.

And yet resilience should not be seen as the preserve of the exceptional – but an innate quality that is found within each and every one of us.

But what exactly is resilience? The American Psychological Association defines resilience as:

“ the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress — such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems or workplace and financial stressors. It means “bouncing back” from difficult experiences.”

In their book Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back, Zollo & Healy define resilience as

“the capacity of a system, enterprise, or a person to maintain its core purpose and integrity in the face of dramatically changed circumstances.”

As we will explore, this ability to bounce back is an invaluable asset when safeguarding your wellbeing, and that of your team, and is an essential quality if you seek a life path less prone to being derailed. Indeed, the cultivation of resilience is increasingly recognised as a key asset amongst employers.

So what determines our level of resilience, or is it predetermined?

Our own resilience is based largely on our personal beliefs, character, experiences and our genetic heritage. Importantly (and inspirationally) it is also determined by our perceptions and mental habits – how we approach and frame setbacks or ‘negative’ events.

The great news is that all of us ( despite our perceived starting point ) can cultivate and build on these positive mental habits, and you don’t have to have gone through a ‘baptism of fire event’ to do so.

Sometimes, it is easier to understand a concept by defining what it isn’t.

- Resilience is not the same as robustness. Whilst this is a common mischaracterisation, it does not honour our current definition. The pyramids of Egypt are robust, having stood thousands of years, but if they are knocked over, would not be able to put themselves back together. From an engineering standpoint, robustness is a hardening of a system, where resilience refers to the adaptability of a system.

- Resilience is not simply recovery.Whilst we can say that resilience is the ability to bounce back, it shouldn’t be confused with recovery. Yes, a resilient person may be able to recover from a significant setback more quickly, but recovery is the return to a previously experienced state, and that is not always desired or useful. Using a biological example, it is not beneficial to simply recover from Chickenpox, we must recover and gain immunity – preventing this occurring again. It is this very mechanism that has allowed our ancestors to survive, thrive, and for us to exist today. When a computer network is compromised by a virus, there can be a significant cost to a business. However, once this has been rectified, recovery to a previous status would be less than beneficial – it is not just the recovery of the system that is desired but the associated learning that is just as valuable.

- Resilience is not about not failing. Failing and other setbacks are part and parcel of improving one’s resilience. As we all know, failures can be defined as learning opportunities. Who hasn’t been able to sufficiently answer a job interview question? Who has not had a failed romantic relationship in youth (and beyond)? Failures allow us to identify cracks in the system, to learn to do better, to adapt.

The development of resilience is in part acknowledging that, inevitability, setbacks will occur. Despite our best efforts, and considering the rapid change of the society today, none of us are immune from change, nor would it serve us to be so. Building resilience develops internal resources which will enable us to live more fulfilling lives. In doing so, we recognise in advance that setbacks will occur, and build our capacity – resilience is a form of preparation.

Don’t get down.

Ruminating on the inevitable risks of life, preparing for danger or threats to our happiness, prosperity & health could, in and of itself, bring you down. Instead, it is best to actively build and frame resilience as an opportunity. Building a resilient mindset leads to greater planning. In the US Army, there is an adage called the ‘5Ps’: Proper Planning Prevents Poor Performance.

Resilience building invites us to plan for life. It implores and requires adaptability, personal and group encouragement, social networking and collaboration. It requires us to take care of our physical and mental health, and to be responsible for how we react to events outside our control. Indeed, from a spiritual level, resilience can give us the confidence to foster a deeper connection and engagement with the world within which we live.

Now who wouldn’t want that?