Thirty-one years ago, Field of Dreams came up to bat as my generation’s most popular sports films of all time. I remember when I first watched the film, probably in early high-school, thinking how ungrateful Kevin Costner’s character, Ray, was throughout the film—taking for granted a relationship he could have had with his Dad, who in my opinion, just wanted to ‘have a catch’ with his son.

But over the years as I grew older, I continued to watch the film, over and over again picking up on pieces of the film that I had somehow missed the previous time watching. Released in 1989, and considered to be one of the greatest baseball films of all time, which it is, Field of Dreams tells the story of Kevin Costner’s character, Ray Kinsella, who builds a baseball field on his Iowa corn farm (unheard of) after he hears a ghost-like voice whisper, “If you build it, he will come” (hauntingly beautiful).

As I watched the film, most of the time, with my father, I began to question the very essence of the film, the very idea that there could be something so magical about seeing a baseball field, lit up at night time, and seeing the ghosts of our past, come out and reliving a life they could have had, but for the mistakes they all (we all) have made in our lives.

And if you make it through that entire film without shedding a tear, I urge you to find a means to connect with yourself, because if that doesn’t do it, I’m not sure what the alternative is.

Field of Dreams resonates with sons and fathers throughout the world and continues to have such an impact today. Our world isn’t perfect. I think that’s evident today, witnessing the world suffer from a global pandemic and social injustice. But neither are families. No family is perfect. There is no ‘perfect relationship.’

Yet, even in the dark, there can still be light. And love.

Last year, the weekend before Father’s Day, I had the absolute honor and privilege of speaking on the phone with an individual I’ve looked up to for many, many years—an actor whose role in the film, appeared in the film’s final five minutes; whose words became arguably the five most important words of the film, and our generation; whose portrayal of John Kinsella still seems to touch the hearts of every father and son out there.

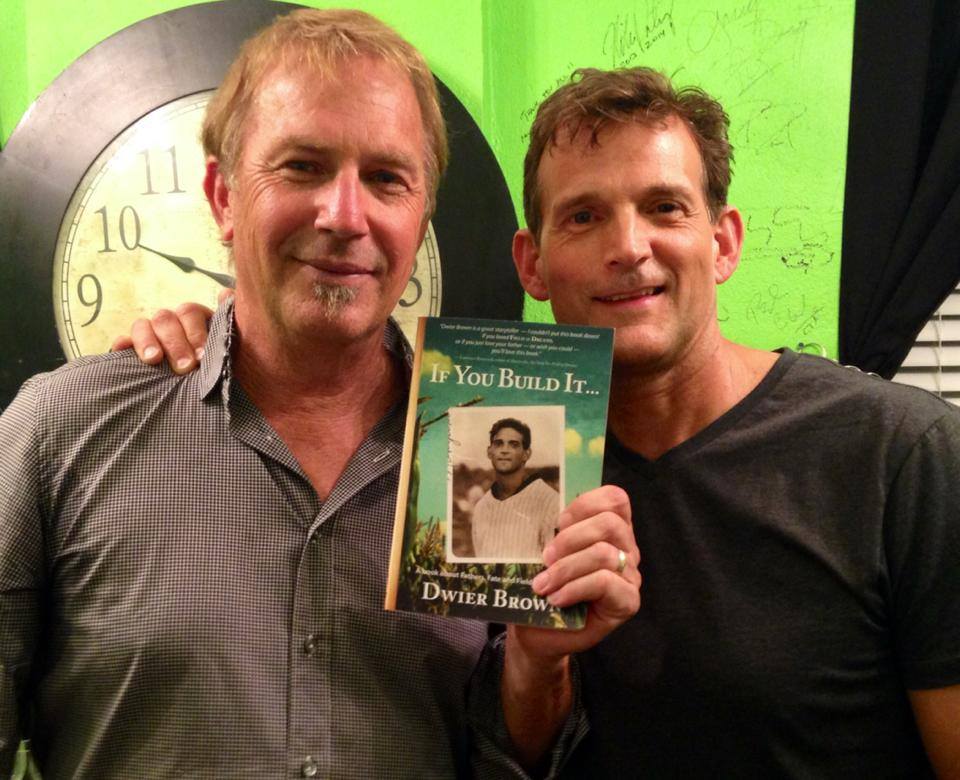

I had the absolute pleasure of speaking with Field of Dreams’ Dwier Brown, now 60, who played John Kinsella, the deceased father to Kevin Costner’s character, Ray Kinsella. Brown, who recently released his book, “If You Build It…A Book About Fathers, Fate, and Field of Dreams”, talks about his funny yet moving memoir and the three different story lines that are brought together as a single tale—Brown’s recollection of heading to Iowa to film Field of Dreams, the encounters Brown had with fans of the film, and a journey into Brown’s own childhood and relationship with his own father. And what a moving book it was—any time Brown is involved, you better believe those tears of joy and love are going to keep coming!

And even more appropriately, Brown was preparing that weekend to head to Dutchess Stadium in New York, attending the Hudson Valley Renegades game against the Tri-City ValleyCats, to meet and talk with fans, ahead of the film’s 30th Anniversary for Father’s Day weekend. Dutchess Stadium was the final stop of last year’s tour for Brown to 40 minor league ballparks in honor of the 30th anniversary of the film.

And you better believe, that the entire hour phone call we spent talking, was absolutely heaven for me. For someone I looked up to and admired in every way, there was plenty about him I didn’t know. And it took exactly one-year for me to put this piece together, in attempts to share this moment accurately with you.

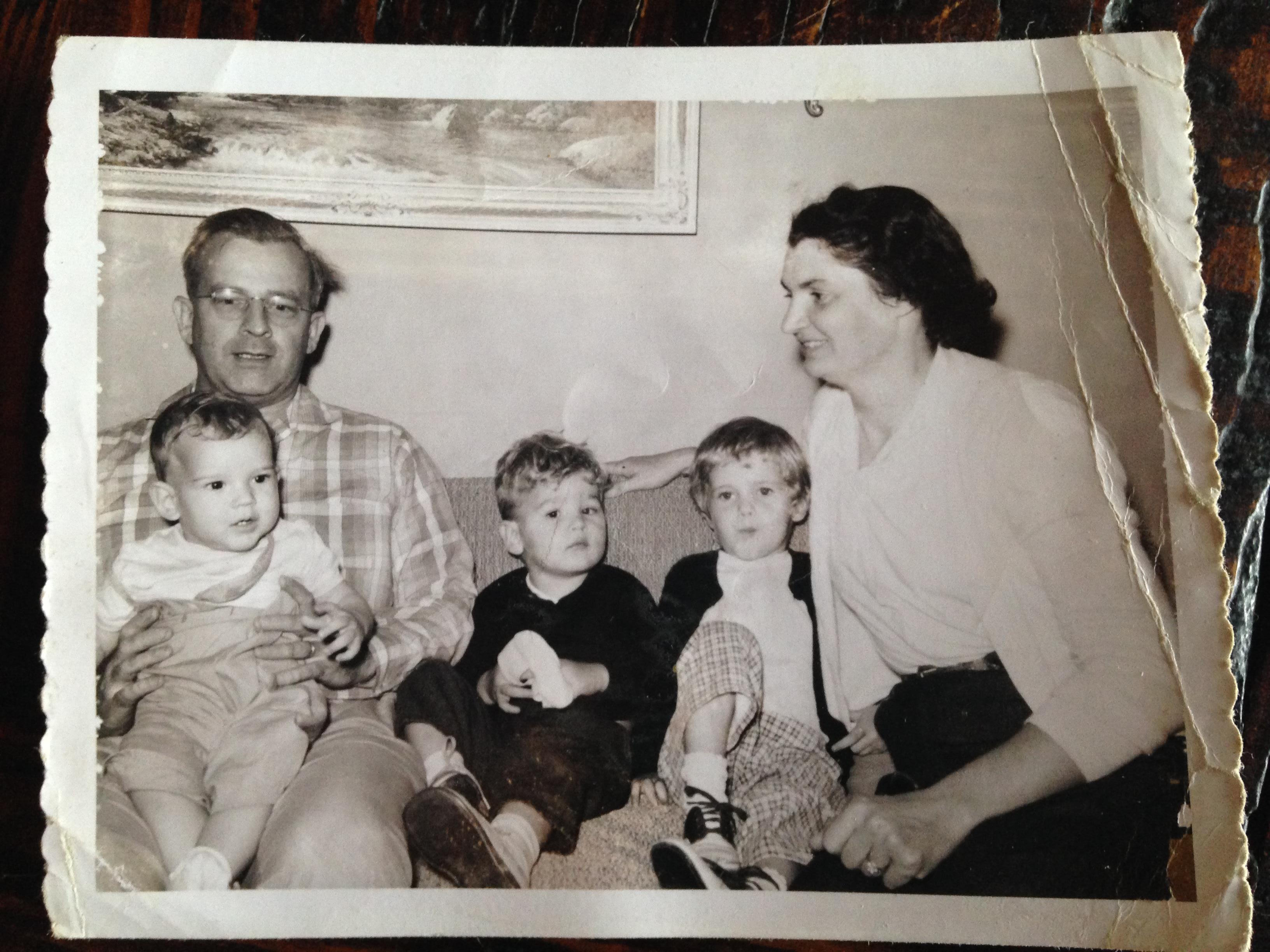

During our call, I learned that Brown, grew up on a farm in Ohio—a place that I had spent the past eight years of my life, living as I attended law school and eventually began practicing law, where like most kids in his town, he along with his siblings, would look for anything that would get them out of farm work.

I learned that Brown, like many fathers and sons, had a sort of ‘strained’ relationship with his father, where parts of Brown’s life can be compared to segments of the film.

But most importantly, what I took away from our call, was that, it doesn’t matter how you characterize your relationship with your father—having any opportunity to “have a game of catch” with your dad, can help just give you just even the slightest bit of understanding as to why your Dad is the person he is, allowing the both of you to ‘love each other’ without necessarily saying the words, “I love you” to one another.

Below, you will find last year’s entire phone conversation with Brown, verbatim, and unedited, where we talk about Brown’s childhood, passion for baseball, desire to be an accomplished actor, and overcoming the obstacles with his own relationship with his father, and how the film we know and love as Field of Dreams, has a lot more subtext than we realize.

Andrew Rossow: Coming into the movie itself, what effect or impact did baseball as a sport have on you, if at all?

Dwier Brown: I grew up on a farm in Ohio in Northeast Ohio in Medina County—middle of nowhere—Sharon Center, population 300. So, I have an older brother and oldest sister, and we played sports year round (to get out of farm work, really!). There were not many organized distractions, so I played baseball, I played Little League, and I write in the book some pretty embarrassing baseball stories. The very first time I played (when I was five years old), my Mom accidentally hit me in the mouth with the bat, and I got nine stitches inside my mouth; that was my very first exposure to baseball.

I started through school a year early, so I was smaller than everybody, and I was not a standout athlete. I actually got cut from my freshman baseball team, but my joke now to my buddies who made the team is, that it’s MY picture that’s in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

I loved baseball, so it’s been really fun to be back at it now at my age and go to minor league games all over the country. It’s been really fun; I’ve fallen in love with the game all over again.

AR: So are you primarily watching? Do you play at all in any sense? Or is this more of just you travel and watch games?

DB: I took batting practice with the Round Rock Express (a Minor League Baseball team of Pacific Coast League and the Triple-A affiliate of the Houston Astros major league club), a week ago when I was down there and that was fun. I played at The Field of Dreams movie site—they had a game, The Team of Dreams event five years ago—and I’m going to play the day before Father’s Day. This year (2019), I’m going to be in a softball game with a bunch of all-stars and Iowa-centric Hall of Fame athletes. Anyway, I’m looking forward to it.

AR: That sounds very fun. So let me ask you this—what brought you into the world of acting and Hollywood? Why did you want to go into that space?

DB: Well, as I said, [chuckling] we were always looking for something that would get us out of farm work, and we lived so far away from people—my sister and brother really started it. We started doing puppet shows in our basement for the neighbor kids. My brother started a little community theater group in the Sharon Center Town Hall. And in summers, we would do one-act plays and melodramas. It was just a lot of fun, and both my brother and sister gave it up and went onto other things, and I just kind of stuck with it. I was in the musical in high school, then I started doing plays in college; and it was always just fun. I was planning to do something else to make a living, because growing up in Ohio, people would say, ‘you can’t be an actor; how are you going to make money?’

When I graduated from college, I was planning to get into advertising in central Ohio, but the economy was in a downturn and nobody was hiring copywriters. So I thought—if I’m going to fail at acting, I might as well do it now when I don’t have any responsibilities; I wasn’t married or had kids to raise or anything.

So, I went to Chicago and got involved with improv, which is something I really enjoyed in college and it just sort of kept happening. I’d get a job and it would pay me more money then I’d ever done doing real work, so I just sort of stayed with it.

I studied with some acting teachers who talked about your emotional life and how acting isn’t lying, as I’d always believed when I was growing up. They talked about acting as being honest; being the truth. It’s really the philosophy of Method Acting, where you find the emotional truth in yourself and bring it to the role.

That level of expressing emotions was amazing to me at the time because I had grown up on a farm with a very stoic family—we never said ‘I love you’ to each other; we never hugged each other. Now, I am doing plays in a theater in Chicago, and I’m hugging people I just met after a show, and I’m thinking, [chuckling] ‘why am I hugging this stranger and I can’t hug my parents?’

I ended up bringing that back to my family in Ohio and I’m very grateful to have done that. I don’t know if I ever got a real, legitimate hug out of my Dad, but it was a process and, with some practice, we finally got him from standing there like a stone, with my arms around him and his hands at his side, to him, at least responding in some way.

So, if nothing else had happened in my acting career other than that I got to tell my parents I loved them and got them to open up a bit, it would have been a successful career. Fortunately, I had other successes, with Field of Dreams being one of my favorites.

AR: Now, getting into that and just by hearing you talk, I can already see the mirroring from parts of your life in Field of Dreams. Is that a fair assessment in terms of the character’s relationship between you and Kevin in the film?

DB: Totally. My Dad didn’t push me into anything the way John Kinsella pushed Ray into baseball, but I did have a rough relationship with my Dad, particularly when I was a teenager.

I had all these emotions inside, and nobody seemed to be talking about them, or addressing them, and it seemed like everything was hypocritical and fake, and I was just angry all the time. Unfortunately, I took it out on my Dad, who was just one of the nicest men and just a quality human being. But, he was the guy who was close, and, at the time, I just didn’t want to be like him.

So, I went through a very difficult time with my dad. Fortunately, I got to make my peace with him several years before he died and I came to understood why he was the way he was. He was from a generation of World War II vets and Depression-survivors—men who had a lot to hold in. They had to put their heads down and work their way through life. So, when I was a little older, I understood that there was a reason why my parents were not heavy with praise, or with affection. And fortunately, I got a chance to figure that out and appreciate my dad for who he was.

AR: Did you ever sit down with him personally, and you had that kind of open chat? Or was it in certain strides that certain things came up and you put pieces together?

DB: There were a lot of little pieces, and in my book I tell about a road trip I took with him, which was just a fluke. You know, if I had thought much more about it, I would have thought, ‘I don’t want to be sitting in the car with my Dad for two hours,’ but it happened and I’ll be forever grateful.

Like with a game of catch, where there is enough distraction that you may start talking about things you may never have talked about if you were sitting face-to-face, he was on the passenger’s side and I was driving, and he was guiding me to my grandmother’s Summer cottage that we had gone to when I was growing up.

We were going to close it up for the winter—take the screens out and put in the storm shutters. I kept prying him with questions—there were so many mysteries in my family growing up; things that just didn’t make sense. Things my Dad didn’t want to tell us kids for fear of upsetting us. Basically, what I found out was, that he had been completely rejected by his father, and I didn’t know that—he wouldn’t tell me that.

And so, I finally got him to tell me his secrets. And I’m driving through these country roads, and my Dad starts crying. I had never seen my Dad cry. I had tried to pry his secrets out of him, but now, suddenly I didn’t want to know—I didn’t want to hurt him any more than he’d already been hurt.

Fortunately, those feelings pass. Sometimes, you have to go through those emotions, and as much as it’s painful, if you don’t go through it, then you end up holding it inside and it eats away at you. So I was very grateful to have questioned my dad, even though at the time, it felt like, ‘oh my gosh, what have I done?’ That was that main thing that helped me get to know him. I mean, after we had that tearful exchange, I realized, ’I’m consoling my Dad. I just watched him turn into an 8-year old boy (he was in his mid-60’s at the time) and I’m consoling him in the front seat of our car’.

Eventually, we got down to the cottage and started to close it up. There’s a creek in front of the place and, one of things we used to do when I was a kid is, we used to dam it up and go swimming in little swimming holes. So, I convinced my Dad to go down there with me, and Dad said, ‘I don’t have a swimsuit,’ and I said, ‘well, let’s just skinny dip. Who cares, Dad? We’re in the middle of nowhere.’

So we went skinny dipping together.

And again—I couldn’t have planned such a thing—I mean, who wants to go skinny dipping with their dad? But it was the most amazing experience and it just broke the ice between us. What could be more symbolic than us being naked with each other in this creek after having had this heart-wrenching conversation in the car?

It’s not like we were suddenly very affectionate with each other, but I suddenly felt like I understood him. So everything that happened when I was younger and everything that happened after, was in a context that I could then understand—‘oh, of course, my dad was secretive about this’— his dad abandoned him, you know? So, I could then bring that understanding to the relationship, and it made everything easier.

AR: Understanding that you have already made your peace, if you could tell him one thing today, what would it be?

DB: Yeah, fortunately. And I’m tearing up right now. I would tell him again, as we all should, just that I love him and that he was a great dad, and…

[tears begin to flow as Dwier is sharing with me]

…if I ever said anything to make him think that wasn’t true, then, I take it back; I would give anything to take it back.

[I interject]

AR: And Dwier, I hope you know much this call means to me. I want to emphasize that this is not just a story to me. I’m very close with my Dad, like you. And over the years, I heard bits and pieces about my grandfather—my Dad’s father was a military man and wasn’t very affectionate towards him; he didn’t know how to translate that.

My Dad has always given everything to me, but over the years, it’s been tough to show that type of emotion towards me, and that’s been a major source of our issues. But otherwise, we get along great, but we are going through that process of what you just told me, and taking it in stride, and understanding more of who your dad is.

Me being up here in Dayton—where my Dad grew up, I’m with some of my Dad’s friends; I’ve connected with people he hasn’t seen since he was a kid, and getting to know his background and what he did growing up, has opened a side of him, that my mother, my sister, I—have never heard. It has allowed me to understand why he is the way he is, and he’s a wonderful man. He loves me dearly, but I wonder why he’s always so hard on me, why can’t he just love me and what not? So, I want you to know, I apologize for making you cry, and this means the world to me.

DB: Please, you don’t have to apologize. This is sort of what my life has become. I end up going to these ball games and, two or three times a game, I have an encounter where I’m in tears, and someone else is in tears, because that’s what I’ve come to represent to people— this Dad, this conversation they’ve never had, maybe with their own dad, and they can have it with me.

Me: Your movie is our movie, as it is for our movie. Your film and what you’ve done, and who you stand for, means a lot to my father and I when we watch that film together.

DB: Well, thank you. I feel just honored to have been a part of it. And it’s my way of keeping my Dad’s memory alive. I don’t mind crying about my Dad. I miss him, you know. I wish that I had always treated him as well as I would treat him now. But, you know, that’s part of the game. I think that’s part of what’s difficult between fathers and sons—that Oedipus Complex. You feel like you have to ‘kill your dad’ in order for you to become a man in some way, you know [chuckling] figuratively, so, it’s part of the gig. It’s just not always pleasant in the moment or afterwards. But there’s nobody I’d rather cry over than my Dad.

AR: With the movie, and I’m sure you have a lot of favorite parts. What is one of your favorite parts, whether it was being part of the movie, filming the movie—do you have a favorite aspect of it?

DB: Um, gosh, shooting that scene, the final scene—I don’t want to call it fun. It was fun as an actor, but it was so raw and vulnerable. And Kevin and I worked hard, and we did a lot of things to make that work. The crew was amazing.

Nobody would know this unless you were there, but we shot that scene over two-weeks, because they decided to shoot it at “magic hour”, which is the fifteen minutes of golden light right after sunset. You could only shoot one little chunk of it at a time before it would be too dark. So, just before sunset, the whole crew would run up from the house or wherever they were shooting, and set up the shot.

And then our cinematographer, John Lindley would check his light meter, until the light was just perfect, and they’d say, ‘Okay, rolling…’

And I’d say, “Is this heaven?”

[recalling Lindley]: “Okay, cut. Alright, let’s do it again.”

[Dwier]: “Is this heaven?”

You know, you do four or five takes of that, and then—

[recalling Lindley]: “It’s too dark, let’s come back tomorrow!”

Then the next day, the same thing would happen, but we’d turn the camera around onto Kevin, and he’d say his line, “No, it’s Iowa.”

It’s remarkable that that scene plays so smoothly, when it was actually done in these short little segments, almost a line at a time. Kevin and I had to get in that delicate, emotional state every day, just after sunset, so we could make the continuity work. So, that was ‘fun’ to shoot as an acting exercise.

I think we all knew that scene was something special. The director, Phil Robinson, was very gentle with us and, I think, the film crew all brought their own dad to that field in their minds. My Dad—his spirit—was flying around that cornfield. And I think Kevin’s was, too, and it made it all the more profound for us, and maybe also for the audience.

AR: Very much so. If you had to explain that final scene, if you want to, what was going on? The reason I ask, and this is more of a personal question for me, you know there is the filming of it, where the audience can determine what to take away from that scene.

Is that relationship between the two, finally established, where your character as John knows this is his son, and (2) do they understand that this is a reestablishment or closure of that relationship? How would you explain that, if you’re allowed to, and also, how you perceived it?

DB: Well, one of the things that I’ve realized over the years, is how perfectly Field of Dreams ends. Because, it doesn’t really answer any of those questions. It leaves it to you to answer them.

There are people who saw the movie who just hated it and thought it was the corniest thing. I mean, Rolling Stone called it the worst movie of 1989, so there are people who don’t get it. People, like Timothy Busfield’s character (Mark), who don’t see the ball players, who would ask, ‘Why are you sitting around looking at an empty field?’

I think the subtext to me in the scene is as simple as, ‘I love you, Dad. I forgive you.’ And ‘I love you, son. I forgive you.’ And to me, that’s all that needs to happen in that relationship. That’s what a game of catch is about, in my opinion. Because Dad can’t say ‘I love you’, when he throws you the ball, he is saying, “I give to you,” and when you catch it, you say, “I get from you.” “I give to you; I get from you.” It’s saying, “I love you,” without the words.

The act of playing catch is the perfect amount of distraction. You’re not thinking about it.. You’re thinking about seeing if you can get a little curve when you’re throwing to your dad, or you’re going to tryout your fastball, or I’m going to throw him a grounder or a pop-fly, but at the same time, you’re saying, “I’m taking time out of my day to be here with you, and although we might not even say words, or we might say words that have nothing to do with what we are really saying, on the bottom line I’m saying, “I love you, I give to you, I receive from you.”

So, ultimately that’s what that scene is saying. Great art is subtext—it’s showing something unseen.

“You catch a great game,” Ray says to John. What would you rather have your dad say to you than ”You catch a great game”?

AR: I want you to know, even though we don’t know each other well, this movie whether it’s me and my father, this movie resonates so well with my generation. I mean friends of mine still talk about. I was at work the other day at the office, and some other people in the hallway, never met them in my life, and they were talking about something about Field of Dreams, and I just chuckled, because you and I had already been emailing a little bit—I didn’t say anything to them—I just walked by and thought that it really is magical, that the movie today still has prevalence and usefulness in how people should treat one another from a family sense, but also to a father and a son.

DB: Thank you, for saying that.

[end of interview with Dwier]

For You Reader

I can tell you; this was probably the most difficult piece I’ve ever written and put together. The level of vulnerability and openness I experienced listening and writing, made this one of the most defining moments of my career as a writer. And who better to have that feeling with, than from someone you’ve grown up admiring on the big screen.

To you reader, thank you for taking the time to read this. Now, here’s my message to you:

To all the sons and daughters out there…

Do better. Be better. It is okay to show emotion. To feel vulnerable. To show your dad, that saying the words, ‘I love you’ is okay—that you are proud to be the son and/or daughter he raised you to be. That you love him for him. That you look up to him. Ask him to have a ‘game of catch’, because you may never know what else will land in your hand.

To you Dwier…

Thank you for opening up to me. For bringing me into your world.

Thank you for opening up my eyes and my heart. Thank you for allowing and providing not just a fan, but a son to find a way to connect with his own father. To one day express himself in how he feels to his father. To resonate with your story and understand that, maybe the love I crave or desire, is hidden away in a ‘game of catch’.

Thank you for the five most important minutes of that film.

And lastly, thank you for the opportunity to know you and be able to reach out at any moment and just tell you, ‘thank you.’

And to all the fathers out there…

Understand that we as your children, don’t always know what’s going on in your head. That we don’t know what you went through growing up. But that we would like to. We want to be close to you. To know you. To understand you. To be the person you raised us to be. Don’t be afraid of opening up and sharing your tears of happiness, joy, fear, and frustrations. Let us share in your world.

Happy Fathers Day!