The world of Black American culinary is a magical language, healing, stories, and myriad realm of artistic endeavors. Through the work, struggle, innovations, aesthetics, and dedication of Black American foremothers and forefathers, the legacy and aesthetics of Soul Food stems from the methodology for Black American mothers and maidens to use food in the healing of their communities and people. Stemming from the work in nourishing their children, men, elders, and overall community, in order to continue their existence in foreign territory, which became familiar. Interviewing Soul Food Scholar, Adrian Miller, readers become more aware to the reality of Black America’s use of food for physical and emotional healing.

1. When you think of Soul Food, what are the images/stories you see? What paintings of artistic memory comes to mind?

I always think of the final scenes of the 1997 film Soul Food when the family comes together after Big Mama’s death. One sees a family split with deep divisions coming together, cooking side-by-side, and ultimately an incredible spread of food. I can’t see how anyone could watch those scenes without their stomachs grumbling. Surprisingly, when it comes to paintings I think of “The Bean Eater” (circa 1580) by the Italian Baroque painter Annibale Carracci. The painting fascinates me because it shows an Italian peasant eating black-eyed peas. It hints at the global reach of West African ingredients.

2. What inspired you to transition into the world of culinary history? Please describe that journey.

The short answer is “unemployment.” I had just ended my stint at the Clinton White House, and I was in-between jobs. The job market was kind of slow at that time, and I ended up watching far too much daytime television. I said to myself, “I should read something.” So, I went to a local bookstore, and while browsing, I noticed a book tltled “Southern Food: At Home, On the Road, In History” by John Egerton. It was the paperback edition of a book that had been written ten years before. Early in that book, Egerton wrote that the tribute to African American achievement in cooking had to be written. I was intrigued, and I reached out to Egerton by email to see if he still felt that was true. He replied that some have dealt with parts of the African American food story, but no one had taken on the full work. With no qualifications at all except for eating a lot of soul food, and cooking it some, I started my research on African American foodways.

3. What specific memories of your grandmother’s OR mother’s cooking, do you recall as initiating your passion for Black American cuisine?

My late mother, Johnetta Miller, was a fantastic cook. Not only was she well-versed in southern cooking and soul food, but she was adept at cooking other foods. I got my initiation by making breakfast for my brother and sister before we went off to school. Once I got better, my mother gradually taught me more things to make.

4. Would you say that there have been different periods/phases in the development of Black American culinary? (Kindly speak on this if you will.)

In my book on the history of soul food, I propose the following time periods in the development of African American foodways.  Bear in mind that a lot of these periods overlap. The first is the Slavery Food period (1619-1865) when millions of enslaved West Africans crossed the Atlantic Ocean during the Middle Passage and tried to replicate their culture and traditions in the crucible of slavery. The Southern Cooking period (1865—present) marks the time that African Americans furthered the development of the U.S.’s most recognizable cuisines. In fact, African Americans were the face of southern cooking for decades. Down Home Cooking (1910s—1960s) describes the mass emigration of African Americans from the South to other parts of the U.S. During this time period, African American migrants tried to recreate home by cooking the southern foods they had before, to the extent that they could get ingredients. “Down Home” was the nostalgic term that migrants used for anything that reminded them of the American South, including food.  The Soul Food period (1950s—present) marks when southern food ceased being a cuisine shared by southern blacks and whites. “Soul Food” became a politicized term that attempted to culturally tie all African Americans, regardless of where they lived. From then on, “soul” meant black, and “southern” meant white. We’re still living with that cultural split to this day. The Neo-Soul  period (1990s—present) represents the many ways that soul food has splintered from its traditional base. We now have health-conscious (e.g., low-fat, vegan), fusion (with other ethnic cuisines) and upscale (using expensive ingredients) iterations of traditional soul food.

5. How do you think that the creation and cooking of “Soul Food” among Black American women and men served as therapy in sustaining Black male and female relationships, AND Black romantic love in the USA?

That’s interesting. I had not thought of soul food in that way because the dominant narrative, to me, about soul food refers to group dynamics: family, extended family and community. Still, I can see how maintaining a connection through food could definitely sustain romantic relationships despite the daily trauma of being marginalized in this society.

6. Name one dish in “Soul Food” culinary that you feel has made the greatest impact on your scholarship. What story does it tell?

It would have to be chitterlings (a.k.a. chitlins) which are pig’s intestines. I had always heard the narrative that chitlins were the master’s throwaway food after a hog killing, and that enslaved blacks were forced to eat them. I was shocked to learn that chitlins were once esteemed by England and France’s white nobility and gentry as early as the 1600s. That means it was once wealthy people’s food. I also learned Yoruba priests also valued innards for holding the life force of an animal. That got me thinking that enslaved West Africans could have valued chitlins as well. We might have been thinking wrongly about chitlins this entire time. Instead of being trash, it may be treasure. This story also shows the social mobility of food.

7. “What comes to mind when you hear the words “Soul Food?” Does your mouth water as you visualize the images of familiar food items taking shape? Do you recall the aromas, sounds, and tastes of a Sunday dinner-all the culinary artifacts of a grandmother’s love? The last 2 words, “grandmother’s love” gives the imagery of “the nannas,” and the “Big Mammas” of our community. What is the responsibility for Black American maidens and young warriors in continuing this tradition?

I think of my mother’s cooking more when I think of the words “soul food.” We had so many great meals, but I think of the meal I described in my book: fried chicken, fried catfish or chitlins as the entrée, the sides are greens, black-eyed peas, candied yams or macaroni and cheese, some cornbread, a glass of red drink and a dessert of either banana pudding, peach cobbler, pound cake or sweet potato pie. We’ve seen an unfortunate break in passing along our culinary traditions. It seems to me that a generation grew up without cooking our traditional food. If our food is to survive, those who enjoy cooking need to teach our youth the soul food fundamentals. Those who receive the knowledge can certainly any food they want, but it would be wonderful to be well-versed in our traditional food.

8. As with other categories of Black American culture, do you fear that “Soul Food,” too, could be commodified, or exploited for the monetary gain of outsiders?

This is already happening. Though soul food has been denigrated and marginalized, elements of the cuisine have now gone mainstream. Though many African American chefs and cooks have distanced themselves from soul food, several cooks outside of our community have celebrated our food . . . and they are making a lot of money from it. Look at how things that have long typified soul food are now showing up on the menus of white tablecloth restaurants: variety meats (e.g,, ham hocks, ox tails), collard greens, kale, okra and fried chicken—especially a super spicy version called Nashville hot chicken.

9. What has been your most memorable time of cooking “Soul Food, ” or being in the company of Black American women and men, who do?

My most memorable times of cooking soul food were being at my mother’s side while preparing holiday meals, and cooking with the church mothers as we did big, special events at my longtime church—Campbell Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Denver, Colorado. Once again, one sees those themes of family and community!

10. Describe your most memorable, colorful, and life-awakening travels, in your education of Black America’s culinary, known as. . .Soul Food.

Well, because I care so much about my subject matter, I spent a year-and-a-half eating my way through the country. I went to 150 soul food restaurants in 35 cities and 15 states. The most memorable part of that journey was the time I spent in the Mississippi Delta. That’s when I felt the most ancestral connection to soul food. Plus, the food was fresh, not canned or frozen, because I was closer to where these ingredients were farmed or raised. I remember one restaurant in particular, Bully’s Soul Food in Jackson, Mississippi. While you’re eating in the main dining room, someone periodically comes out to a table and strips fresh greens and peels sweet potatoes!

And so, as we continue to reflect on the ongoing work for Black America to heal pains of the past, while celebrating Beauties of its present, the culinary aesthetics of this peculiar people is again brought to the table. While feeding others, Black Americans created new eatery for ourselves. Those Maidens and Mothers who re-connected with Earth’s fruits; despite attempts to remove femininity from their Being. Those Fathers and young Warriors, who re-connected with their cultural, feminine image in order to receive culinary healing from her existence. Reviving their Being and Soul. This is the storytelling and artistic quilt of Soul Food. A Soulful healing, while healing the Soul!

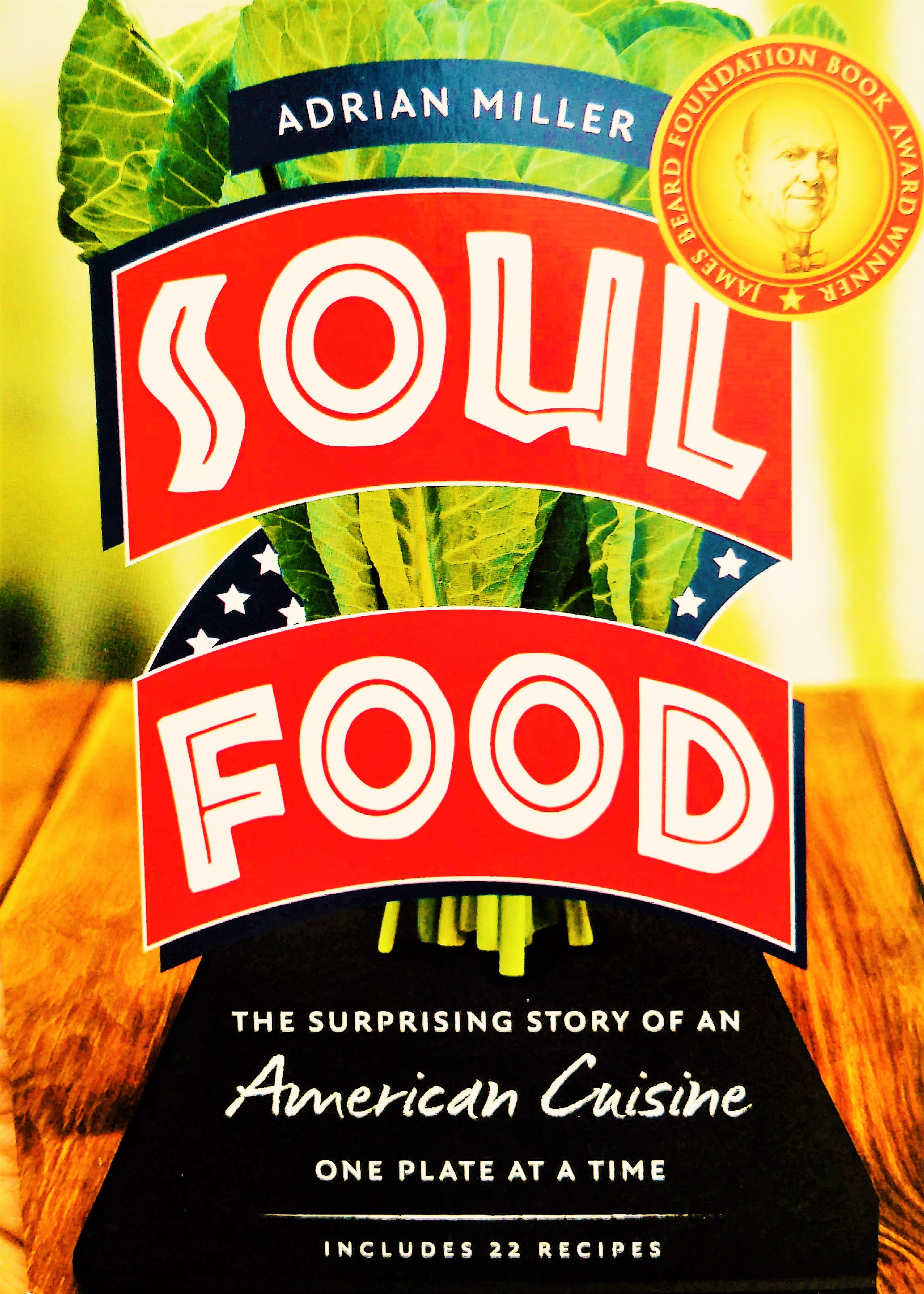

The Scholar, Himself

Adrian Miller is a food writer, attorney and certified barbecue judge who lives in Denver, CO. He is currently the executive director of the Colorado Council of Churches and, as such, is the first African American and the first layperson to hold that position. Miller previously served as a special assistant to President Bill Clinton and a senior policy analyst for Colorado governor Bill Ritter Jr. He has also been a board member of the Southern Foodways Alliance. Miller’s first book, Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time won the James Beard Foundation Award for Scholarship and Reference in 2014. His second book, The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, From the Washingtons to the Obamas was published on President’s Day, 2017.

For more information on the work of Mr. Adrian Miller, you can go to www.soulfoodscholar.com.