You don’t lead by hitting people over the head – that’s

–– Dwight Eisenhower

assault, not leadership.

There is a problem with many line managers – they make

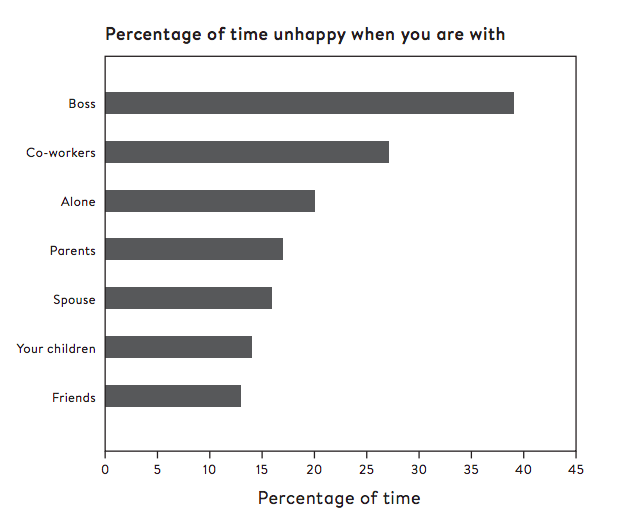

the people who work for them miserable. The Nobel Prize laureate Daniel Kahneman has pioneered the study of time-use to find out which times of day are happiest for people, and the answer is quite shocking. As the figure below shows, the worst time of day is when you are with your boss. The person who should be inspiring you and appreciating your work makes you feel lousy. There must be something deeply wrong with our philosophy of management.

Most work is not enjoyable

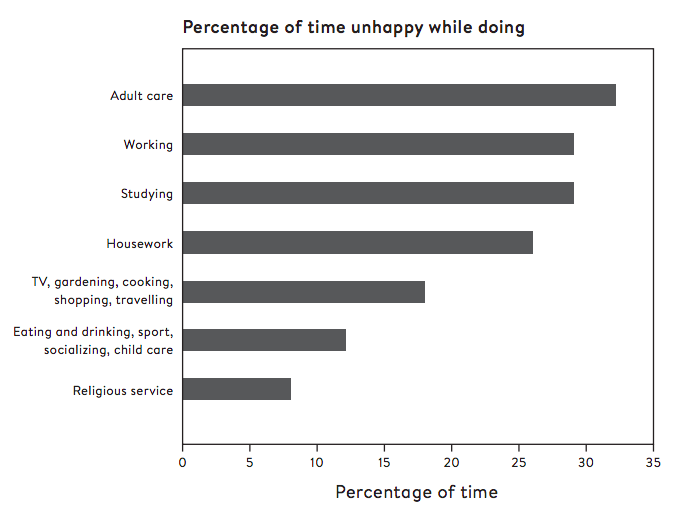

There is another, hugely depressing finding that comes from these studies. Most people don’t much like their work – compared with almost anything else they might be doing. The next figure shows how unhappy people are when they are doing different things. For the average person, working is about the most unpleasant activity there is. This is not of course true for everybody and quite possibly it is not for many readers of this book. But for the average American citizen it is just that. And the same has been found in Britain. An ingenious app called Mappiness bleeps people at intervals and asks what they are doing and how happy they are. They are least happy when they are at work – the only thing that is worse is being ill in bed. Moreover, things are not improving and stress is increasing.

Unhappiness depends on who you are with (USA)

Unhappiness depends on what you are doing

But if work is so often unpleasant, one might ask why people are so unhappy if they are unemployed. One reason is of course that they are poorer, but, as we saw in Chapter 2, it is not only that. Work makes you feel needed. Work supplies a purpose in life, a reason to get up in the morning, a sense of being useful – even if it is often boring or hard. It provides a social connection – to other workers and to the customers of your labour; and it provides a sense of meaning and purpose.

But can we produce better ways of working? One thing is obvious: the culture at a workplace is not immutable, nor are the details of how the work is organized or how the workers are paid. If current practice makes people miserable, it can be changed. Even if the job to be done is unappealing, it can be organized in a more appealing and motivating way. Work is not, as the Book of Genesis would have it, a punishment for the sin of Adam.

Happiness and the bottom line

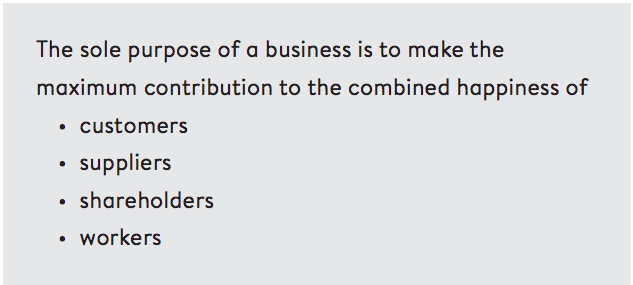

But is it reasonable to expect employers to care about the happiness of their workers? There are two reasons why they should – moral and prudential. The moral reason stems from our Policy Principle: that the objective and raison d’être for any organization must be that it contributes to the happiness of the world. This includes the happiness of the shareholders, the customers, the suppliers and the workers (see box below).

Contrary to the dogma of many business theorists, it is not only the happiness of the shareholders that should count. Shareholder value has become an increasingly dominant objective in recent years, but all four stakeholders matter, and in British law at least the directors of a company must ‘have regard to’ the interests of all of them. Profits are essential for a company to survive and grow. But they are not the reason for having companies or for giving them all the protections they receive from the state. Companies exist to serve the interests of all their stakeholders. The workers are generally fewer in number, it is true, than the customers, suppliers and shareholders, but for them it is a much bigger part of their life. So Corporate Social Responsibility starts with the workers.

The second reason for caring about workers is prudential: happy workers work better. Suppose that in 1984 you had invested $1000 in the US companies listed in the 100 Best Places to Work, while your brother invested $1000 in the rest of the market. By 2007 you would have earned $500 more on your investment than your brother did on his. This does not mean that every policy that makes workers happier is good for the bottom line. But it does mean that the happiness of the workers is a serious issue for managers.

This is not surprising since a happier environment attracts and retains better workers. Happy workers are also more productive. This is borne out both by experiment and by observation. So here is a typical laboratory experiment. Two groups of people were given the same specific tasks and paid according to their performance. People who before the task were shown a happy film clip did 12 percent better than people who were shown a neutral clip. Moreover, happy people tend to do better in their careers. For example, if you take US adults aged twenty-two and follow them up seven years later, those who were happier by one standard deviation when aged twenty-two earn 5 percent more later (everything else being constant). The weight of evidence supports the conclusion that happy workers generally work better.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.