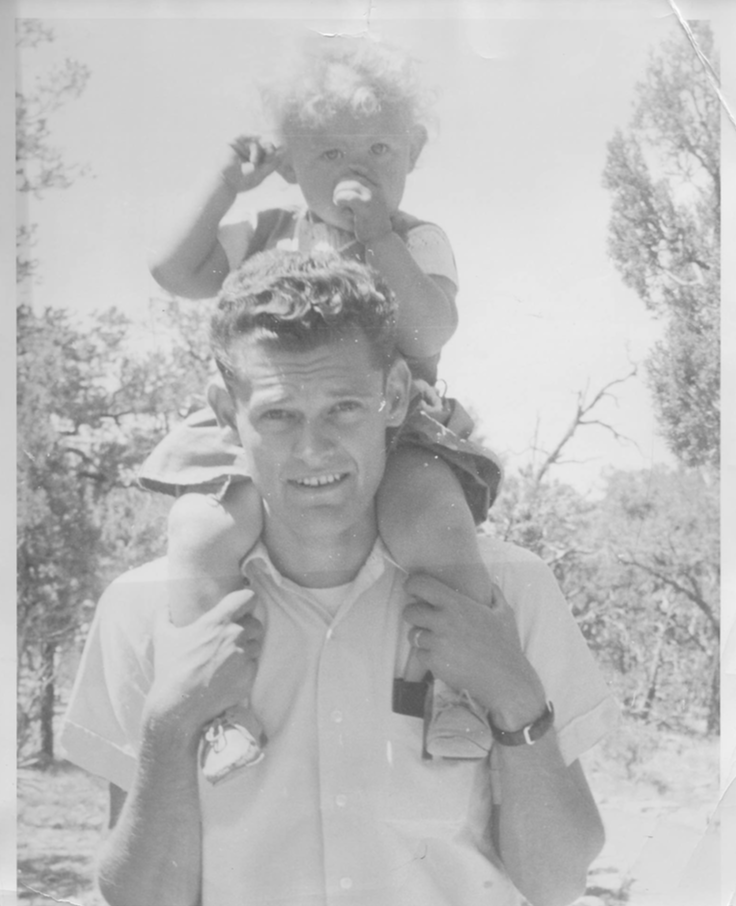

As the daughter of an FBI agent and the grand-daughter of a judge, I grew up surrounded by the law. Looking at photos of my grandfather, his brothers, and their father was like looking at a Western where the sheriff was always in town. My great grandfather was a sheriff on a fruit and livestock ranch in White Bluffs, Washington. His sons all grew up to be law men.

My dad was always chasing the bad guys, wearing the white hat, and telling me the stories about how bad guys never win, and justice prevails. He hunted bad guys, and he also sought justice in other ways. When I was about twelve and out for a drive with my dad, he stopped at the railroad as the crossing lights and barrier came down. My dad turned to me and said that a year ago the barrier hadn’t been there and a teenager, on his way home from prom that night had barreled on through the tracks right on to an oncoming train. My dad said that while he couldn’t bring the teenager back, he could make the railroad put up crossing barriers there and everywhere along the track where crossings were missing.

He’d learned from my grandfather who had grown up on the livestock and fruit ranch when it was just being settled. Many years later, the Federal government, after making many claims to the ranch years earlier during The Manhattan Project, made additional claims on the land once owned by my grandfather, and various native American tribes. My grandfather, too frail to travel, wrote his testimony, and I traveled to Washington D.C. and testified in my grandfather’s stead before a U.S. Congressional committee on behalf of the affected landowners, including my grandfather and the various tribes.

You could say I have justice in my genes.

As a Federal Prosecutor and then covering cases as a legal journalist for more than fifteen years, I have seen so many defendants tried in the courtroom and so many verdicts rendered. Through it all, there is always one constant that makes me feel confident in every outcome: the jury. That group of citizens, brought together with one goal: to weigh the evidence presented by two battling opponents and to render a fair and impartial verdict, based on that evidence alone, and not swayed by their prejudices.

My first nonfiction book in a new series,HUNTING CHARLES MANSON:The Quest for Justice in the Days of Helter Skelter, has hit the bookshelves everywhere. As I reflect on the years of research I did for this book and the bird’s eye view I had as the only journalist at a recent parole hearing for a member of the Manson “Family,” I can’t help but return to the respect — yes, awe — I feel when I think about our legal system.

I do believe that our jury system, while not perfect, is the best system in the world and it is solely based on the fact that our citizenry continues to show up for duty — pretty much voluntarily. Sometimes a criminal defendant will elect to have his or her case heard by a judge, but that is a rarity. Most often cases are heard by a bench of his or her peers. And that system would fold but for our just showing up, plain and simple.

I know that some people may think of jury duty as a hassle and, depending on the case, it can sometimes be demanding. But it can also be an eye-opening glimpse into parts of our society that we don’t come into contact with in our normal lives as well as an opportunity to set aside our own biases and consider the evidence against our own core ethics and values.

My grandfather is no longer with us on this Father’s Day. But I hope to carry his frontier spirit with me every day. And, Dad, every day is Father’s Day because you’re with me every day, not just Father’s Day.

Thank you for giving me the justice gene.

My Dad and Grand Dad overlooking the Columbia River (Washington State)