The short version of Stacey Minor’s story is that she grew up in a part of Chicago now considered a “food desert” because of the lack of fresh food available and has come up with such a great way to help that she’s received more than $1.1 million of support.

Settling for that version, however, is like grabbing a meal from a drive-through window when there’s a savory spread available.

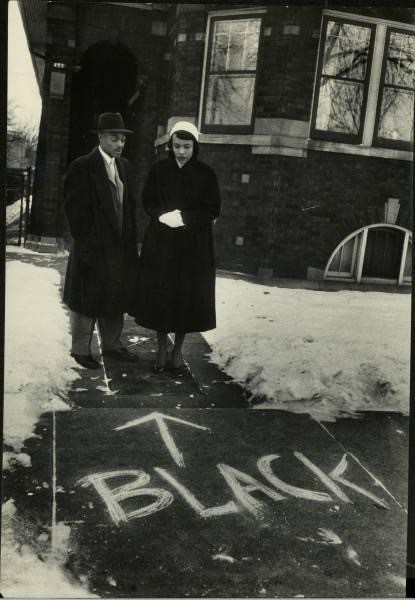

The more delicious version of her tale traces to the South Side of Chicago. More specifically, the Chatham neighborhood. Zooming in more, to the house of Matthew and Juanita Strickland, the one once seen in Chicago magazine with the word “black” painted on the sidewalk with an arrow pointing toward their front door.

The Stricklands were Stacey’s grandparents. Matthew worked for the city. He was friendly enough with Mayor Harold Washington that as a girl she visited his office. Her favorite trips downtown, however, were to see Juanita at her office with the Chicago Housing Authority. Stacey dreamed of one day wearing a suit and leading a team like her Grandma.

Back to the house, though.

The Stricklands took pride in their meals. They were always made from scratch using quality produce. That included peaches, okra, green beans, tomatoes and more grown in their back yard.

Their daughter – Stacey’s mom – wanted the same for her kids. When they moved into the Roseland neighborhood, they shopped at mom-and-pop grocery stores. Then the area deteriorated. They had to drive 45 minutes for decent produce. Things got better when they moved to Chatham, only to see another community crumble; again, they had long commutes for groceries. Still, it was worth the effort.

Stacey heard friends talk about frozen meals or picking up fast food. It never made sense to her. Didn’t everyone treasure fresh, homemade food eaten with loved ones?

***

Stacey was in eighth grade when a guidance counselor recommended a high school for her and her best friend Josephine. A new place called Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences.

“We looked at each other and were like, `Who-uh-culture?!’” she said, laughing.

Soon, Stacey got hooked on biology and horticulture. During a summer internship at the University of Illinois, she experienced those fields overlapping.

Working for the USDA’s Department of Plant Pathology, Stacey cut plants, put them into a blender and extracted their DNA. With sick plants, this helped determine the fungus causing the infection, so they knew how to treat it.

“Once I got into it, I LOVED it,” she said. “I couldn’t have imagined doing anything else.”

***

Stacey attended the University of Illinois eager to continue studying plant biology. Yet she never considered a career in it.

She’d never met a black scientist, much less a black woman scientist. From her perspective, becoming mayor of Chicago was more realistic.

Then she got a recruiting brochure from a major agricultural biotechnology company. The document pictured a black woman holding an alfalfa plant. Stacey told her mom, “I’m going to work with her.”

***

Sure enough, the company hired Stacey. She got an apartment in a suburb surrounded by waterfalls and trees.

As Stacey and her sister drove into the neighborhood for the first time, her sister sang the opening line from “The Jeffersons” theme song: “Well we’re moving on up …”

On Stacey’s first day at work, a colleague came to greet her. It was the woman from the brochure.

Her name: Dannette Ward.

“My mom’s name is Donnette,” Stacey said. “It felt like fate smiling on me.”

***

Everything was great at first – the salary, the science, even meeting the minority farmers who grew their crops.

Then Stacey noticed something. All black employees worked in soybeans. All Asians worked in wheat. Indians worked in potatoes, Caucasians in corn.

Then she learned that some peers with less experience and less education had higher salaries. They were all white men.

Then Dannette was laid off. As were other friends.

Her pals didn’t know how to find another job. Neither did Stacey, but – eager to help those in need – she learned. She then taught her friends how to update their resumes, leverage their professional networks and prepare for interviews. It worked.

“Whoa, I like this,” she thought. “Let me do this for myself.”

***

Stacey eventually got recruited by Challenger, Gray and Christmas, a Chicago firm that’s essentially a professional matchmaker.

She saw her role as going deeper than pairing companies and employees. More like a ministry, she sought purpose-based connections. Then she evaluated the purpose of her own career.

“What can I do to help the world be a better place?” she wondered.

Meanwhile, returning to Chicago also meant returning to the poor grocery options of her youth.

Although she considered 45-minute drives normal, she also knew it didn’t have to be that way. She’d lived in neighborhoods served by grocery delivery companies.

In the summer of 2017, she was thrilled to learn that one delivered to her ZIP code. Then she saw what they offered her neighborhood.

“It wasn’t stuff I could identify with culturally,” she said.

She mentioned this one day to a friend in New Jersey. He said his neighborhood also lacked good grocery stores. Other urban areas did, too, he said.

So the scientist began researching. Stacey found an article about “food deserts.”

“Our problem has a label!” she thought. More digging showed this was far more than an inconvenience.

Poor access to fresh food leads to a poor diet which leads to poor health. That’s not just a theory. Stacey discovered that some communities have more dialysis centers than grocery stores.

“Surely there’s a company out there that’s doing something about this,” she thought.

Further research showed there wasn’t.

***

The aha moment came when Stacey remembered the minority farmers that she’d met through her science job. In addition to their commodity crops, many grew fruits and vegetables. However, they struggled to find buyers.

“They can’t sell their produce and I can’t buy produce in my neighborhood? That is a huge disconnect,” she thought.

Then: “Ding! Ding! Ding!” That was the sound of all the concentric circles of her life snapping into place.

***

Stacey started with the farmers she knew. Next came other people in her vast network – folks in IT, sales, marketing, supply-chain specialists.

By early 2018, she was ready to launch a pilot program. A friend recommended she target not merely a food desert, but the worst sector within one. That led her to Altgeld Gardens, a public housing project surrounded by wastewater and a garbage dump.

At that time, the Chicago Housing Authority offered Altgeld residents a bus ride to a grocery store – but only every other week. Folks had little choice but to stock up on frozen meals, canned goods and other items loaded with preservatives.

Then along came Stacey’s company, named Sweet Potato Patch in honor of the silky pie Juanita taught her to make.

Sweet Potato Patch offered boxes of fruits and vegetables, meal kits with easy-to-follow recipes and precooked meals, all ordered on an app and delivered door-to-door.

“This is a godsend,” residents told her.

***

Last April, Sweet Potato Patch received $1 million from Chicago’s Neighborhood Opportunity Fund to build a headquarters.

In September, my organization, the American Heart Association, invested $100,000 through our Social Impact Fund, along with support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois.

Her new space is expected to open in March.

Sweet Potato Patch will continue serving Altgeld Gardens – and Rosewood. Chatham is being eyed next. There’s even talk of expanding down I-90 to Gary, Indiana. And to the St. Louis area.

The food is so good, and so healthy, that some companies buy her premade meals and meal kits as a benefit for their employees. Among those clients: Challenger, Gray and Christmas, where Stacey still works.

***

The momentum she’s generated has sparked publicity, which has led to calls from angel investors.

Everything that helps the bottom line also further validates her vision. And it all serves as a tribute to the values and lessons instilled by everyone who shaped her journey.

You could even say it’s the best thing that ever grew from the seeds planted in the garden of Matthew and Juanita Strickland.