Once upon a time, I processed purchase orders for a large university. We often made large dollar value purchases near the end of the fiscal year to spend all of our budgeted funds. One year, we purchased a software license early and I followed a template of a prior year’s purchase on the order form. There was a “Notes” field that was usually left empty. In that field, I typed the next year “Fiscal Year 20XX” and thought nothing more about it.

A few days later, I noticed that the funds had been encumbered in the wrong account. Our purchasing department had read the field and interpreted that I had meant this order for a different account.

This was a dastardly problem.

I could not change the purchase order, nor could I change funds encumbered in the accounts. With the fiscal years changing, the accounts were locked for transactions. The power to correct the order was not at my level. As far as I knew, I had made a huge mistake. I went to my boss to explain the problem.

He said “Call Mr. So-and-so at the such-and-such office and ask to have a 1:1 appointment with him and then explain the problem to him just like you did for me.” Now this was the equivalent of saying ‘Go before a stranger, stab yourself, and bleed out until death takes your soul.’

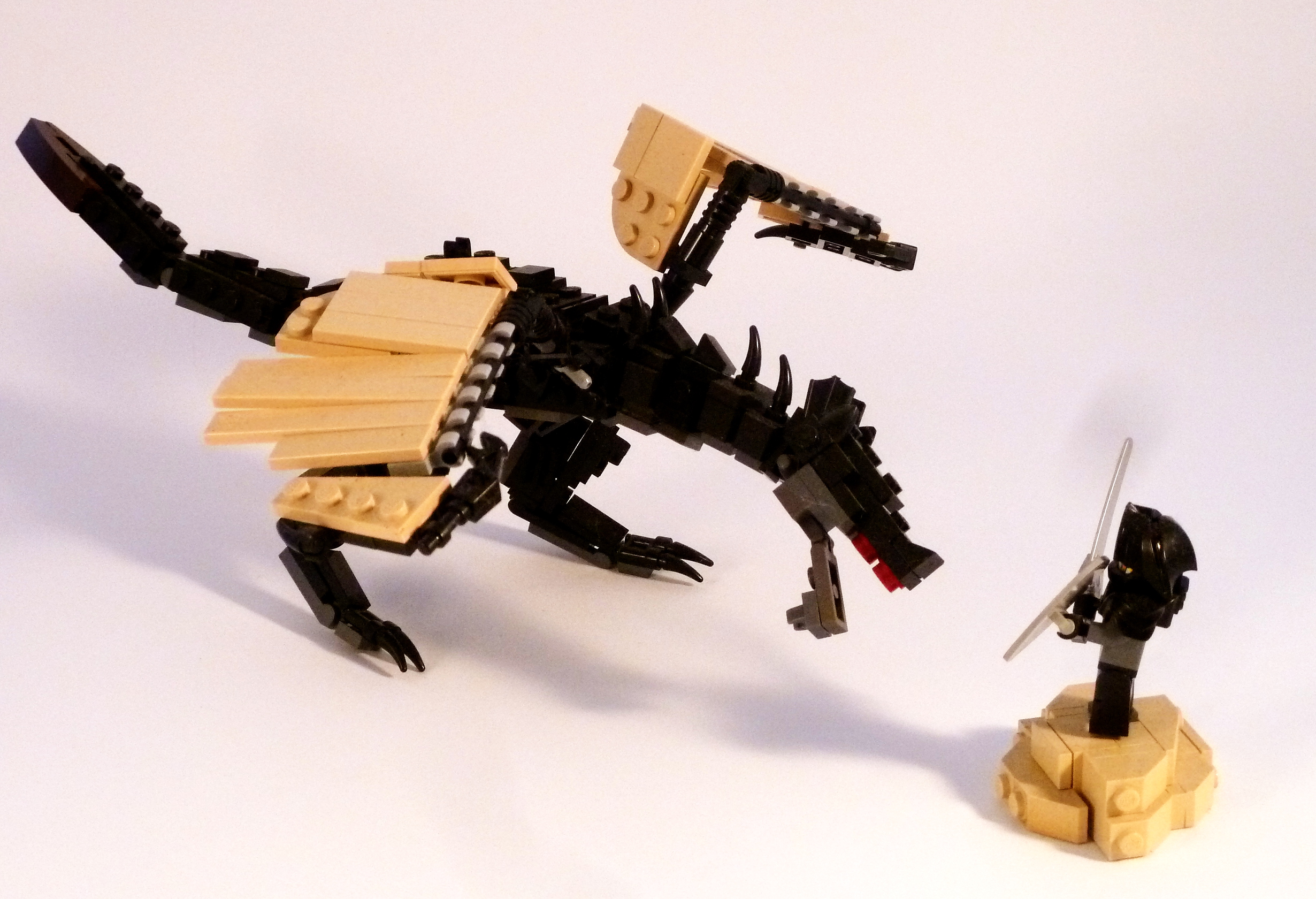

Said another way, I was facing a dragon.

I could fully see this dragon before me. I could see the razor sharp teeth, I could see the growing fire glow in the belly, and I could contemplate the acid brewing in the stomach.

Why did I take this problem so seriously? It was a monetary error greater than my annual salary. I had committed a violation of one of my most closely held Suze Orman rules: Make yourself so valuable to an employer that it is cheaper to keep you than to fire you. Firing me at that point would be easy.

On shaky legs, I walked into Mr. So-and-so’s office. I still remember it. Big office. Polished wooden desk that glinted in the light. I explained my problem.

He said, “What account number is the money in?” I gave it to him. Tap tap tap on the keyboard. “What account number do you need the money in?” I gave it to him. Tap tap tap on the keyboard.

“There you go, all set, Heather. Anything else I can do for you today?” he said.

“No, uh…that’s it.”

Numbly, I walked out. Alive. With my job. Dragon slayed. What just happened?

Over the years, I have had the chance to think a great deal about this story. I know now that:

- Mr. So-and-so was the campus bursar, literally the only person on campus who is authorized by the state to move funds account to account. Hence, only he could solve my intractable problem.

- Likely his access was restricted to his office terminal. He could only do that transaction from his polished wooden desk. Hence I had to go to his office.

- If my boss was reading me correctly, he knew the hardest part of what he had asked me to do was the first step: ask for help.

Lesson learned?

When you are facing your big, fire-breathing dragon, it is often not your job to slay that dragon. Your job is to find the Dragon Slayer. This person slays that particular dragon

all

day

long.

And they get paid for it. And they think it’s no big deal.

Repeat this to yourself:

find the Dragon Slayer.

I’ve met other dragon slayers over time. As a remote worker, I find them most often when I’m eating fettuccine alfredo at some in-person work event, and I’m complaining about the biggest work problem in my life. A stranger from across the table will say, “Oh, I fix that all the time. You just do this, this, and then this.” Picture me dropping my fork, mouth wide open.

Dragon slayer, thy name is…whoever you are on the other side of that table. You just saved my (work) life.

See the secret here is to realize that you are not alone. This is a connected leadership philosophy. I’ll write more about this in the future, but here is a hint: Every time Jean-Luc Picard faced a difficult situation on the Enterprise, he’d turn off the view screen, and turn to his team and say one word, “Options?” It’s a brilliant leadership maneuver.

Over time, I’ve become a Dragon Slayer myself. I can take care of some problems that cause others to fear. It’s pretty cool. I know exactly how to do it. You just do this, this, and then this.

Best of all, however, is that I share this Dragon-Slayer-Finding Power with others when they come up against their intractable problems. I share that polished wooden desk story to give them hope that finding a dragon slayer starts with asking for help. It’s not so hard to ask for help. The other steps come easily.

When seeking Dragon Slayers while working remotely, I love to pick up the phone and say to a colleague, “I know you faced this one. What did you do?”

After our conversation, I thank them and hang up the phone, and whisper “Dragon Slayer.”