God is love, or so they say. Yet, in our increasingly secular society, one in which most people I know spend far more time on dating apps than in places of worship, it is clear that for some, the opposite has become true: Love is God. While this may seem like a relatively benign turn of phrase, there are tremendous implications when the pursuit of romance replaces the pursuit of the divine as our primary holy quest.

If we are not conscious of this modern-day reversal, we run the risk of undermining our relationship to both love and God, relationships I argue need to be stronger and deeper perhaps now more than ever. As our collective psyche is drawn further into a world of deep fakes, AI, and a merciless attention economy, ensuring we are in touch with the numinous could be considered nothing less than a spiritual emergency. Thus, we must begin to re-conceptualize a romantic partner not as the destination, but rather as a fellow traveler on the road towards transcendence.

As a clinical psychologist, my job is in part to create a safe container for patients to talk about whatever is on their minds, from their secret fantasies to the typically unspeakable fears they ruminate on in the middle of the night. These days however, God has somehow climbed the charts to become one of the most taboo topics in the treatment room. While patients may causally detail their lurid sexual encounters, they become shy and almost whisper when they bring up the G word. I too find myself avoiding the topic, well aware that depending on a patient’s upbringing and belief system, the mention of God has the potential to be confusing, alienating, or downright triggering.

So let me clarify here: When I say God, I am not talking about a specific religion. I am definitely not talking about a coherent, concrete deity that lives in the sky. I am however talking about a belief in something larger than oneself, a beyond that cannot be seen by the naked eye and thus, requires a leap of faith. I am talking about a pervasive and wild, benevolent mystery.

In the last century, “larger than oneself” has become siloed, often meaning just a tribe of two — you and a lover. Ernest Becker, author of The Denial Of Death, called this shift the “Adult Romantic Solution.” While our death anxiety was once quelled by religious beliefs, with the secularization of the West, we became reliant on romantic love as our primary way to self-soothe, make meaning, and manage our fear of mortality. Our hungry souls now gobble up the Disneyificaiton of love and the wedding industrial complex, both of which feed the fantasy that once we’ve found a partner and spent an extravagant amount of money on a party for family and friends, we will have finally found refuge, be at peace, and live happily ever after.

The implication: What was once the search for divine oneness has gradually morphed into “looking for the one.”

The appeal is understandable and quite seductive. A partner is far more tangible and defined than what, by its very nature, is intangible and hard to define. “Oneness” includes you and thus, involves the deep, life-long internal work of dismantling one’s ego and idea of separateness. “The one” on the other hand, is external, at our fingertips, something we can touch and attain, potentially just a swipe away.

Unfortunately, I have seen this perspective have negative consequences on the lives of countless patients; from the malaise of feeling one’s life has lost its meaning and purpose without romantic love, to full-blown love addiction. With love addicts, partners are ascribed magical, god-like qualities, which make the addict feel high in the beginning of a relationship, but inevitably result in excruciating disappointment when that partner fails to live up to their deification. Rather than looking inward, the addict often repeats this cycle of limerence with another lover believing if they just find the right person, this pattern will cease to exist.

Risking hyperbole, I would argue that romantic love has replaced religion as the opiate of the masses. Instead of the poppy growers of Asia getting rich, this time it’s the dating startups of Silicon Valley. We buy what they sell because we are eager to fill the god-sized hole in our hearts. And in this way, the supply can never exceed the demand.

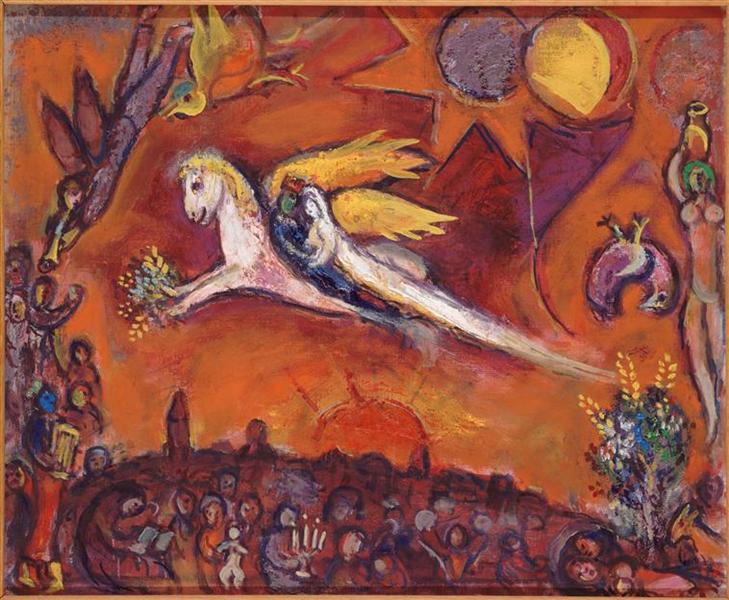

While this may sound grim, I want to be clear that I fervently endorse the infatuation stage of a relationship. Who doesn’t want to experience the intoxicating effect of worshiping at the altar of love? Who doesn’t want to be at least a little love drunk, believing in fairytales and relating to the songs and poems written by others in a similar state? This period of time is not only a wonderful, rare opportunity for lovers to feel more fully alive, but it is also a fundamental part of a long-term relationship; a phase that becomes concretized in a romantic narrative, looked back upon fondly, and used to ignite passion in the subsequent years.

The problem lies not with the high, but rather the withdrawal. Can you tolerate it when that golden sheen rubs off your lover and a fundamentally flawed human being emerges? Simultaneously, can you stay put when your partner begins to see your flaws, your humanness too? Or, does it suddenly feel as if God is dead?

Paradoxically, I believe that the moment romantic love is removed from its unrealistic place in the heavens and brought down the earth — the moment that flimsy rom-com fantasy bubble bursts — is the very moment you have the opportunity to truly make love a place of spiritual practice. With your partner no longer under the pressure to live up to a god-like fantasy, you can finally begin to see, accept, and love them for who they really are. And it is in this process that the act of loving indeed becomes holy. As Carl Rogers, the father of humanist psychotherapy says, “People are just as wonderful as sunsets if you let them be. When I look at a sunset, I don’t find myself saying, ‘Soften the orange a bit on the right hand corner.’ I don’t try to control a sunset. I watch in awe as it unfolds.” Love as a place of spiritual practice means that we, as often as we can – like one would if they had a porch facing west overlooking a mountain range – watch in awe as our partner unfolds.

And when we’re not watching a sunset, but rather a storm, all the better the circumstances are for practice. As is the case with some forms of meditation where you are meant to sit without moving even if you have an itch on your nose or your foot has fallen asleep, part of the work in long-term relationships is to tolerate the disease and conflict of co-existing with another fundamentally different human being. I am not saying one should stay in a relationship if they are in tremendous pain. That would be like trying to meditate while in need of an appendectomy! I’m also not saying that one cannot want aspects of a relationship to change. Growing together overtime is natural and necessary. I am however saying that sometimes the acceptance is the change. And that when we have found a partner who we have indeed fallen in love with and whose particular flaws we feel uniquely suited to manage, it is part of our spiritual work to widen our window of tolerance for discomfort in the relationship, just as it is our spiritual work to widen our window of tolerance for discomfort in our lives at large.

We may then begin to pursue our connection to the divine in other ways. Often strong relationships have a third thing — that thing that is larger and beyond, grounded in meaning and purpose, which perhaps helps foster connection to that benevolent mystery. While this could be the direct exploration of relationship to source, it could also be broader, including becoming a part of loving community, being of service, or supporting an impactful cause. Whatever it is, let that third thing expand your aperture around what is holy, expand your definition of love to include, rather than just focus on your partner. Then, instead of facing your loved one perpetually searching for the divine within the human, you can turn outwards and walk side-by-side together into the deep.