It is 5:00 am on November 12th, 2017, the temperature is chilly, but not too cold, and a breeze blows from the northeast. Sobrius, my 1972 Dufour Arpege, is ready to go. I have ten gallons of water in jerry-cans, five gallons of spare diesel; the boat is clean, organized, and everything unnecessary has been removed. I have a new collision bulkhead in the bow and new dorade vents, which I built. I have way more food than I need. My 12-foot surfboard/dinghy/life-raft is onboard, taking up half of the salon. We are ready for a singlehand sailing adventure to Cumberland Island. I’ve never been there, but I hear it’s nice.

The sky is dark, but the stars are out as I untie the dock-lines from my slip at Ortega Landing in Jacksonville, FL. I motor out into the Ortega River and hail the drawbridge for an opening. This one opens on demand, but the Main St Bridge, three miles away, only opens five times a day, and I need to catch the 6:45 opening.

Just outside the Ortega River I raise the sails and shut off the engine. I set the autopilot and stand on the bow with a spotlight as we sail across the St Johns River towards the channel. The yellow beam of light cuts through the thin layer of fog above the water, illuminating a fuzzy shaft of space and occasionally a buoy marking a crab trap, causing me to quickly return to the cockpit to change course.

Once across the river and in the deep channel, I turn us to port and into the wind. The current is against us and I realize that I’m cutting it close for the bridge opening. I start the engine to gain some speed and drop the jib, ineffective as we need to go almost directly upwind. If we don’t make the bridge opening, I’ll have to wait until noon for the next opening, which will completely throw off the schedule for making it to Cumberland Island today.

As I near downtown Jacksonville and its colorful predawn skyline, a train horn sounds in the distance. A train bridge lies just before the Main St Bridge and is usually open, however, should there be a train coming, it closes, blocking the way for all but the smallest of boats. But we are still twenty minutes from the train bridge, and I feel confident this train will be far gone before we get there. The time is 6:20 and the eastern sky is showing the first light of dawn.

But as we approach the train bridge I can see the silhouettes of the train cars as they pass, blocking out the lights of the city behind them. It’s a slow train, moving about as fast as a casually-ridden bicycle. The train is still crossing as we approach. Another sailboat is behind me, moving faster than us. I hear them hail the train bridge on the VHF, asking how much longer the bridge will be down and if they are going to let us make the Main St Bridge opening. But this is a futile question; the train must pass and the bridge will remain down until it does so. It’s now 6:35. I start to accept that I will probably not make the 6:45 opening. My backup plan is to stop at Jacksonville Landing, between the train bridge and the Main St Bridge, and have a long breakfast while I wait for the noon opening.

The current is strong here, and we are only going 2.5 knots at full throttle. I continue motor-sailing towards the closed train bridge, and magically, the train passes and the bridge opens just as we get to it. The other sailboat is back on the VHF, asking the Main St Bridge if they will delay their opening so we can pass, and the bridge operator is accommodating. A third boat is waiting, and all three of us motor under the bridge after it lifts straight up.

For the rest of the day I motor-sail down the river, but up-current as the tide is coming in, and upwind into the ENE breeze. We pass under three more bridges, by the loading docks of giant container ships, tugboats, waterfront houses, industrial areas, uninhabited islands, the Mayport Ferry, and finally the Naval station and its warships as we enter the Fort George Inlet in the late morning.

The tide has turned and is now pulling us out to sea. The engine is running and the sails are up. The forecast today is for continued ENE winds at 12-15 knots and 5-8’ seas. The swell is coming from the NE and is counter to the outgoing current. I expect there to be large waves in the inlet, and I can see whitewater exploding over the jetty to my left. The time is 11:00 am.

The waves increase the further we get down the inlet, two feet, four feet, six feet, eight feet, even a few ten-foot waves bounce us around. But none are breaking, and I steer us through the rolling landscape and into the Atlantic Ocean, turning NNW to get out of the inlet and its current and waves as soon as I can. The new collision bulkhead gives me extra confidence, and I feel like Sobrius sails better with her stiffer bow, but this is probably just my imagination.

I kill the engine and we sail for a short while, NNW towards land, until I tack us East. We hold this course for nearly an hour and then tack back to NNW. I check the chartplotter to make sure we don’t get too near the shoals in front of Nassau Sound. It all looks like deep water from here, but the chart shows shallow water reaching out far into the ocean south of the sound. After a while, as we near the charted shoals, I think I can see breaking waves ahead. I switch sides in the cockpit and pull the tiller over. Holding the tiller between my knees, I release one jib sheet, holding it taut until we pass across the wind, then I let it go and pull the other sheet in as fast as I can. The winch sings its metallic song and I cleat the sheet off, then sit back down.

As we sail East, I check the remaining distance to the St Marys Inlet, which will lead us to Cumberland Island. The inlet is still ten miles away, and we are having to take a zig-zag route because of the wind. We are also sailing against a current created by the nor’easter that has been blowing for a few days, and the wind is decreasing. Our speed over ground is only 3 knots and the time is 1:30 pm. Reluctantly, I decide to do a headsail change. We need all the power we can get.

I go below and fetch the big black bag that contains the genoa, my largest headsail, and take it up on deck. I clip my harness to the jackline on the coachroof and make my way to the bow with the genoa, where I hank it on to the headstay with the sail’s many bronze spring-loaded clips. I then unroll the big sail on the windward deck, go to leeward and untie the lazy sheet from the working jib, take it back to the genoa, and tie it to the sail’s clew. Now I go back to the cockpit and press the auto-tack button on the Pelagic autopilot, then return to the mast. As Sobrius slowly swings into the wind, I release the jib halyard from its mast cleat and the sail falls to the deck as I pull it down with its downhaul.

I go back to the bow, unhank the jib, transfer the halyard and downhaul to the genoa, slide the old sail under the jackline, move to the mast, and raise the genoa. I go to the cockpit and trim the sail, then back to the bow, where I hank the working jib under the genoa just in case I need it later, if the wind picks back up. I untie the remaining sheet from the old jib and tie it to the clew of the genoa. The headsail change is now done and I return to the cockpit, where I sit down and take a break while the autopilot steers us ENE.

We are now sailing at 4 knots, speed over ground, tacking towards the St Marys Inlet. But I know that we will be arriving at the inlet after dark, and I’ve never been there before. I hope that the buoys are all lighted, and if they are not, I’ll have to stay out in the ocean until daybreak. I start the engine. We need to do what we can to get there before dark, if at all possible.

The chartplotter shows some shoals nearly two miles outside the inlet, and although it says they are at a minimum 17 feet deep, I decide to play it safe and go outside of them, as they could surely be more shallow than indicated. As I near the inlet I see another sailboat pass between me and land, heading south, crossing over the shoals that I am avoiding. I hope she doesn’t run aground.

The sun is setting and I am finally rounding the green buoy and entering the St Marys Inlet. The tide is falling and the river is pouring out water, counter to the incoming swell. The inlet is rough. Large waves pick up my stern and push us forward, then leave us in the trough, nearly coming to a halt.

Although water is rushing past Sobrius’ hull, our speed over ground is fluctuating between 0 and 2 knots. We are moving at a slow walking pace, with two miles to go until we are out of the ocean and its relentless waves. The sky darkens. The horizon ahead is filled with flashing lights, green, red, yellow and white. The chartplotter tells me that the next red buoy is flashing at six-second intervals and the green is a quick-flash. I search the forest of lights and find the two I seek. These are a little brighter than the rest, as they are the closest, and thus fairly easy to keep in sight once I find them. But when the bow rises in the waves it blocks my view of the horizon. I have to focus completely so I don’t let us get off-course.

The stern lifts and whitewater pours into the cockpit as Sobrius surges forward. A wave has broken over our transom. I don’t turn around, I must focus on the lights ahead. The red and green buoys are getting closer, but as they do, the sensation is disorienting. The water of the inlet is flowing fast past Sobrius, but the buoys seem to sit still. I feel like I am drifting towards the green buoy, so I steer more to starboard. When we are between the red and green buoys, it seems like we are not making any progress to pass them. Instead they seem to move laterally, towards us and away. It is unnerving.

But finally, they are behind us, and I don’t look back. I look at the chart plotter and determine the flashing pattern of the next two buoys. I find them on the horizon and focus intently on them. Behind them is a yellow light higher on the horizon, and this light doesn’t disappear when the bow is lifted by a wave. So I focus on the yellow light and steer towards it.

I look at the chartplotter to try to determine what this yellow light is, but quickly give up; it’s a pointless task. But when I look back up, the horizon is black – no lights at all. I look left and right, where am I? The lights are all off to starboard, and I turn us right, chastising myself for my lack of focus.

“Focus” I tell myself. It only takes a moment to get off-course. Now I must find the red and green buoys again, and the yellow light, which has moved a bit to the right since I went off course. I risk a glance behind us to make sure that we are still in the channel, and all seems well.

This goes on for nearly two hours before we pass the north jetty, which blocks the waves. The water starts to calm down. The buoys don’t disappear beneath the bow anymore. But there are lights all over the place, and I have to be very careful to select the correct red and green lights to head for.

I feel a wonderful sense of peace when we are inside the inlet. Although the water still rushes by us with the outgoing tide, the waves disappear and Cumberland Island blocks the wind. The water is smooth as glass and the stars are out. The night is beautiful. I’m almost there, and the hardest part is behind me. The time is 8:00 pm.

I’m keeping the red buoys to starboard and looking for a small channel on the right, outside the main channel, leading to a small area where I intend to anchor, next to Dungeness Dock on Cumberland Island. The small channel is unmarked, but the chartplotter shows a few white flashing lights along its bank and a red buoy marking the left side of the channel.

I shine my spotlight to starboard and I see low trees and a muddy beach, surprised to see land so close. But the depth gauge, thankfully working now, shows 19 feet. The white lights I see don’t match the flashing patterns indicated on the chartplotter, so I must be careful. I set the autopilot, drop the genoa, and motor forward slowly, standing on the bow looking for obstacles with my spotlight. I go back and forth from cockpit to bow, altering course as necessary, studying the white lights, and looking for crab traps, shoals, or anything we might not want to run into.

Finally I identify the channel where I intend to anchor, and I spot a structure that must be Dungeness Dock. To port is the anchorage I seek, empty except for an unlit reflective sign emerging from the dark water. I steer us towards the sign so I can read it. The chart shows an obstruction in the vicinity of the sign, and the sign reads “OBST”. I motor about in loops south of the sign, checking the depth, and I douse the mainsail. The water is all as predicted by the chartplotter, 8-10 feet deep.

The wind is blowing from ENE, and I point us into it, about 100 yards south of the OBST sign, and put the engine in neutral. I walk to the bow and open the anchor locker, pull out the old CQR, and lower it into the water. When I feel it reach the bottom, I stop letting out chain for a moment to let it lay properly, then I begin letting out more chain and rode. I let out what I estimate to be 80 feet, cleat it off, and put my hand on the rode in front of the bow to check for vibration that would indicate dragging. There is none. The anchor is set, and another feeling of clam and peace overcomes my mind and body. The time is 9:00. I’ve been sailing for 16 hours and now am safely at my destination. The night is dark, the stars are out, the wind is peaceful, and I go to the cockpit and call my father, who’s been watching my progress via the SPOT website, and share my successful journey with the man who introduced me to sailing.

After a bowl of chili and tuna I sleep soundly in the gently rocking boat and the silent night.

At daybreak I make coffee in the French press and then oatmeal with honey and dried fruit that I eat right out of the pot while sitting in the cockpit and taking in the view. Green and yellow marsh grass waves in the breeze to my left. Cumberland Island is to the right, forested and with a narrow beach, sandy in some areas, muddy and covered in oysters in others. The twisted branches of short oak trees hang out over bluffs above the beaches. A small sailboat motors downwind from the north, passing us to starboard.

After breakfast I ready a backpack with shoes, water and snacks. I put on my foul-weather gear – yellow bibs and red jacket – and remove the 12’ surfboard from the salon which I put in the water, tied to Sobrius. I find the kayak paddle and carefully step onto the board, kneel, untie, and paddle upwind and up-current, angling only slightly towards land. The surfboard glides across the water with minimal friction and we have no problem beating the current. I angle more towards land, and we drift onto the sandy beach at Dungeness dock.

I pull the board out of the water, take off my sandals and yellow bibs, put them into the backpack, put on my shoes and strap on the backpack. I hike through the forest. It’s been a while since I’ve been in the woods, and I love it. Brown oak leaves carpet the trail. Palmettos rise to shoulder-height reaching up with big green and pointy fronds. Live oaks dominate the canopy with their thick curving branches and green leaves. The forest is silent.

I hear an animal to my left and three deer jump and run. I try to capture them on camera, but am not quick enough.

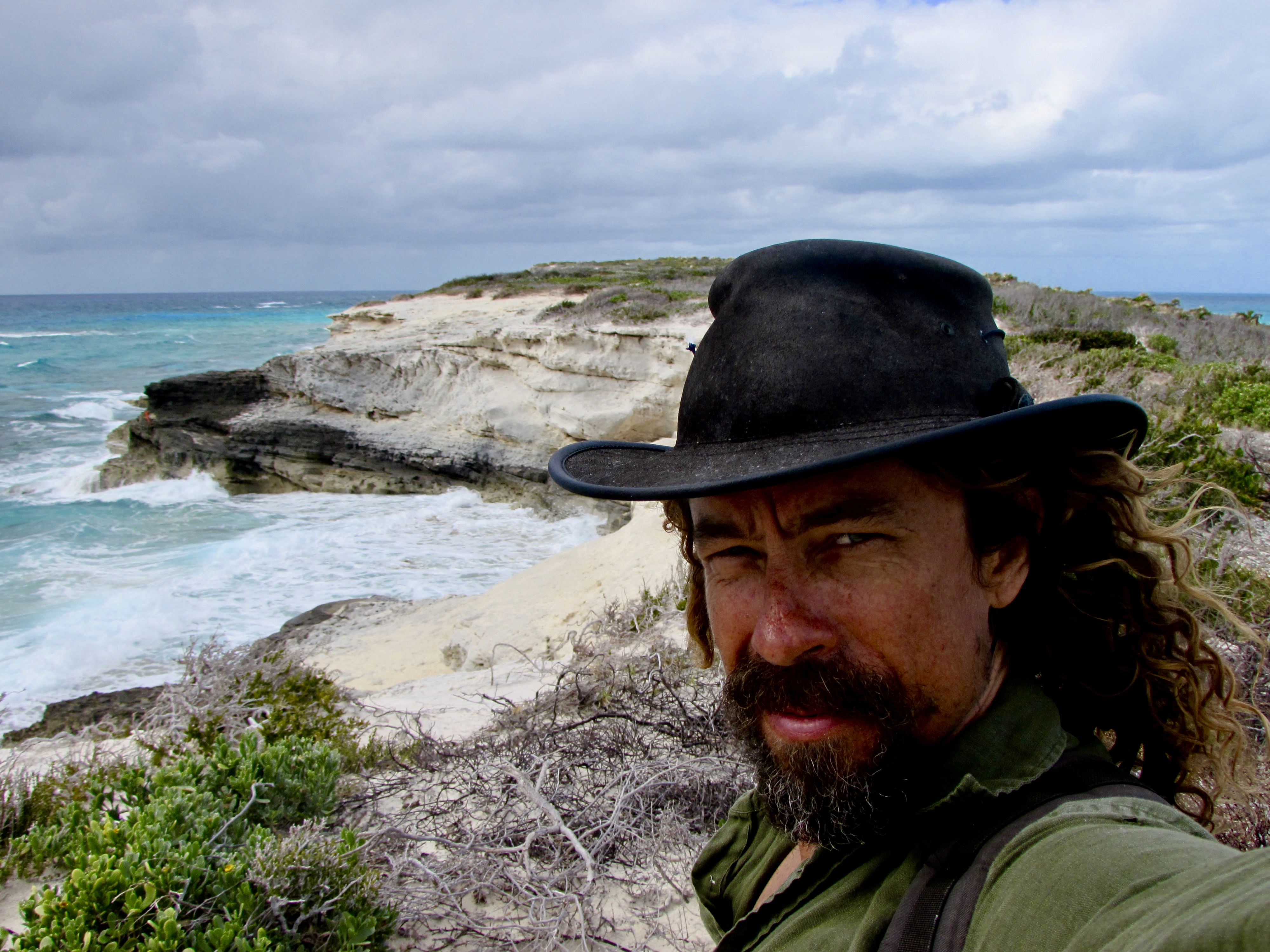

I wander through the woods for a couple of hours, passing another dock, crossing a sandy road, choosing trails intuitively. I find another deer, this one is a buck with antlers. I try to sneak up on him, and he snorts at me before running. I climb a tree and try to meditate, with very limited success. I end up on the beach, where I smell horses, but see none. I walk south along the wide and empty beach until I find the marker indicating the entrance to the campground. I walk along a boardwalk that the horses apparently use, indicated by a pile of scat. When the beach gives way to forest, the low and branching oaks create a magical scene of twisting and curving branches.

As I walk past the campground, I pass a few tourists pulling carts full of gear, heading in for a long stay, coming in from the dock I walked past earlier. Soon I come to a sandy road and turn left. I know there are some ruins on the island, and I think they must be this way. I’m not sure what sort of ruins they are, but I think they are from a plantation of some sort. I really don’t know what to expect.

The road leads to a clearing and I can make out a grand entryway, rows of oak trees, and tall stone and brick works in the background. The ruins are way more impressive than I anticipated. It appears to have been a grand mansion. Tall stone walls reach for the sky, stairways, iron grates, brick walls, large window openings, and patios all abound. I walk around the structure, and the backyard is even better. A grand fountain, dry now, decorates a huge green yard viewing the river beyond, with a long-range view of the water and marsh beyond.

To the east of the ruins, past a white statue with a low wooden fence around it, is a field where horses are grazing. These must be the fabled wild horses of Cumberland Island, and I approach to within 20 yards, as close as I dare. They take little notice of me as I take video with my iPhone.

I walk around the duck pond, where I see a raccoon doing the same, in the direction of where I think Dungeness Dock must be, and the dock comes into view. My surfboard lies where I left it, waiting for me. A man and a woman are fishing on the dock. He is trying to untangle the fishing line on his reel. I walk out onto the dock and take a picture of Sobrius lying calmly at anchor.

I put my bibs and sandals back on and carry my board to the water, where I paddle back to Sobrius. I make a bowl of split-pea soup for lunch and relax for the rest of the day, soaking in the solitude.

I had planned to take the ocean back to Jacksonville, but after listening to the weather report on the VHF radio, I debate whether I should take it or the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) instead. The seas have been building, and are forecast to be 6-9 feet tomorrow, with 20-25 knot NNE winds, gusting to 35. I feel like I could handle the conditions, although the inlets would be very rough. The ICW would be more scenic, the winds would be less, and of course there would be no waves. The only issue is depth. I’m not sure how deep it is and the charts don’t show depth in some areas.

I consult my friends on Facebook. One responds that the ICW should be no problem. I’m leaning towards this option. The sailing would be downwind and fast, with lots of gybes, and no directly-upwind legs. I feel like this is the conservative and safe option. The decision is difficult, with no obvious answer, and I sleep on it.

I wake early and prepare Sobrius for sailing, putting away the genoa and readying the main and working jib. I pull up anchor and raise the sails as we drift downwind and down-current. The tide is going out. I sit in the cockpit and steer us onto course, quickly reaching 6 knots. We pass the red buoy and I need to alter course to starboard, necessitating a gybe. I pull the main all the way in and ready the leeward jib-sheet by wrapping it around its winch and pulling in the slack. I steer us to starboard and the main bangs across the cockpit; Sobrius leans hard from left to right. With the jib now back-winded, I steer with my knees and let out on the windward sheet while pulling in on the leeward sheet hard and fast. The jib catches the wind and fills with an audible pop, and I cleat off the sheet. Sobrius accelerates in the 20-knot wind. I let the mainsail out and we accelerate more, crossing the main channel. I need to gybe and turn to port again soon.

We sail fast towards the St Marys Inlet, then turn to starboard and enter the narrow ICW, with fishing docks and then a big paper mill on the left. We pass a heap of boats piled up on the shore, probably victims of Hurricane Irma. Soon a small fishing boat towing a net passes to port. Pellicans and seagulls screech and dive in its wake.

I stay focuses on the red and green buoys, both in front of and behind us, careful to stay in the narrow channel. “Red west” I repeat to myself. In the ICW the “red right return” rule does not apply, instead, the red buoys are inland, and the green buoys are on the ocean-side of the channel. I remember this as “red west”, which I repeat in my head as I navigate the narrow channel.

The paper mill with its foul smoke fades away behind me and the landscape is dominated with yellow, green and brown marsh grass on both sides of the channel. Sailing fast downwind, I frequently have to gybe and avoid obstacles. I pass a group of sailboats anchored just past the mill. A barge is dredging ahead to port, and leaves very little room in the channel to pass. I watch the depth gauge intently. It drops as low as 7 feet.

As I approach a hard right turn, I am hailed by a large powerboat coming up behind us. The captain asks if he can pass. I respond that I’m about to gybe and ask if he could wait a minute until I change course? Sometimes I veer off-course during gybes. He waits, I gybe smoothly, bringing a smile of pride to my face. The big boat passes and accelerates, soon disappearing over the horizon.

I pass through a swinging train bridge, then under a high bridge leading to Fernandina Beach, and into the wind-shadow on the other side. It’s very peaceful here. The water is smooth, the shore to port is forested, and I see a blue tarp over what appears to be a lean-to in the woods. Perhaps a hermit lives there. To starboard is marsh, and beyond lies the mainland and grand, well-spaced houses. Slowly the breeze comes back and we continue on. I debate putting up the genoa, but Nassau Sound isn’t far away and the wind is sure to be stronger there. We turn directly downwind and I gybe the main but leave the jib where it is, wing-on-wing. I focus on the direction ahead and the wind vane at the top of the mast, keeping the wind directly behind us. I remind myself to point to tiller at the main if it starts to luff. I can’t allow the wind to get behind it and swing it across the boat in an unintentional gybe. I’ve done that before and vowed never to let it happen again. Twice in the past the mainsheet has hurt me when this happened. Luckily Sobrius wasn’t damaged.

The channel widens and I sense Nassau Sound is coming up, and indeed it is, as I can see the wide opening and two bridges in the distance where A1A crosses the water, following the beach.

The chartplotter dictates that I head towards the bridges, just past the south entrance to the ICW, before turning back to enter the channel there. Very shallow water lies all around. In some places it is only one foot deep. The tide is going out and the current is strong. The sound is an inlet to the ocean, but the water is too shallow to be navigable, and the bridges are too low to pass under anyway. But the current is strong and flowing out, pulling us towards the bridges and the ocean. However, the NE wind is also strong and we have plenty of power to sail back upwind after I gybe and turn to starboard. But first I must pass around a buoy to avoid the shoals.

Rounding the buoy, I change sides, pull in the main, pull the tiller to me, steer with my knees, release the windward jib-sheet and pull in with the leeward sheet. The jib swings halfway across the bow and stops, back-winded. The leeward sheet is caught on a turnbuckle. I should have had the turnbuckle taped up, but it’s too late for that now, the sheet is caught. The current is trying to pull us out, but the main is doing enough without the jib to keep us moving upstream. However we are drifting to port and the bank. I steer us towards the upwind side of the entrance to the ICW. The channel is very narrow, but it looks like we’re going to make it, even though the back-winded jib is trying to push us to the left and into the bank.

We are at the entrance, on the upwind side, like I wanted, and I turn us straight down the channel. All is well. But the jib-sheet is still caught on the turnbuckle. Now we are going more downwind and the main is blanketing the jib enough that it is not under pressure. I set the autopilot and spring forward to release the sheet, but as soon as it is released and I turn around to get back to the cockpit, Sobrius lurches to a halt, the bow falls, she rolls onto her left side and turns 90 degrees to the right. I grab a shroud to keep from falling over. We are aground!

I get back in the cockpit and assess the situation. Downwind is deeper water. I pull in the sails and Sobrius heels way over, with the toerail almost in the water, but we do not move. I release the main all the way, move to the leeward deck, and push on the boom, back-winding the main, trying to create reverse thrust. Still we do not move. I return to the cockpit and start the engine. While it warms up I ponder that I should have had the engine running as I crossed Nassau Sound. It is becoming a theme, I should probably make a rule, always keep the engine running when in inlets.

After the engine warms up, I put it in reverse and throttle up. We don’t move. But then the sound of the engine changes, smooths out, a familiar vibration ceases. I put it back in neutral, then forward and look out over the stern to see if the propeller is pushing water. But the water is calm and remains unchanged as I shift back and forth from neutral to forward. The propeller shaft has probably come disengaged from the transmission coupling. This has happened in the past, but I fixed it and it hasn’t happened since then, a year ago. I go below, move everything off the port quarter berth, open the transmission access panel, and confirm that this is the case.

I slide the prop-shaft back into the transmission-coupling and try to tighten the set-screw that holds it in place, but the screw is frozen.

Back in the cockpit I run the engine, put it in forward. I see the turbulence created by the propeller and decide that as long as I don’t try to use reverse, I’ll at least have forward power. The tide is coming in and eventually we will probably float off the sandbar. A few boats pass, but nobody hails on the VHF, nobody stops, nobody makes eye-contact. They all just drive on by – except one sailboat whose captain asks if we will be ok until the tide comes back in. I say we will and thank him for asking.

I keep trying to maneuver the sails to push us off the sandbar. Soon a big trawler approaches from the south and I decide to ask it to push a wake at me to maybe bounce us off the sandbar. I hail it on the VHF, but get no answer. I hail a second and a third time, and still get no reply. I assume they can hear me, but don’t want to be asked for help.

“Approaching powerboat, can you send me a wake and try to bounce me off this sandbar”

Now he responds. “You want me to deliberately wake you?”

“Yes sir”.

He speeds up and sends us a wake, but alas, we remain stuck.

By now the tide is coming back in and I am resigned to wait. I alternately sit still and relax, then get up to play with the sails. I throw out a small kedge anchor to try to pull us free. But the sails don’t push us free and the kedge finds nothing on which to hold.

As a member of a towing company, eventually I decide to give them a call and get a free tow off the sandbar. They send a boat right away and within a half hour I can see a flashing red light atop a boat coming from the north.

He pulls up alongside and tells me to douse the sails, then throws me two lines and tells me to cleat them on the bow and stern on the high side of Sobrius. Right away he starts pulling Sobrius hard into the direction from which we came, causing Sobrius to stand back up and heal the other way. But this puts enough strain on the forward cleat that the deck under it begins to rise up, and a crack starts to form around it. I step back and stare in horror as a small piece of fiberglass under the cleat pops off.

But Sobrius begins to float and I run to the cockpit and put her in gear. Nothing happens. The shaft must have pulled out again. And again we run aground. The towboat pulls again and we are free. But without the ability to motor, I move to the mast and raise the main. The towboat captain yells at me “You can’t raise the sail, we have paperwork to do!”

I couldn’t care less about his paperwork, I need to avoid running aground again. But we were still attached via tow lines, so I drop the sail. He pulls us closer and keeps us in the channel as we drift downstream.

As we drift I tell him about the prop shaft, then I go below to inspect it. It is gone. A small trickle of water comes in through the shaft-tube. The shaft must be jammed against the skeg in front of the rudder. If it was completely out then a strong flow of water would be coming in.

“Where do you want to be towed?” he asks.

“How far can you tow me?”

“Where are you going?”

“Ortega Landing,”

“All the way up in Jacksonville?”

“Right, but I can sail the rest of the way.”

“Nah, the channel ahead’s narrow and twisty and turny; you’d be tacking into the wind. No. Let me take you somewhere safe. Ortega’s outside my territory, lemme call Mayport.”

Later, after much conversation with his partner in Mayport: “You’re going to have to come out-of-pocket to get there.”

I nod “How much?”

More conversation on the phone ensues.

“He says worst case scenario will be $2500.”

“No way. Just take me somewhere I can anchor, or hold us still for a minute while I get in the water and push the prop shaft back in.”

“Water’s too cold.”

“I have a wetsuit.”

“I can’t hold us still, and that’s just too much liability. I can’t do that. Hold on.”

More conversation on the phone.

“He says he can take you to Sister’s Creek dock, right by the St Johns River.”

“Without coming out-of-pocket?”

“Right.”

“OK, as long as it’s all covered by my membership and I don’t have to pay anything extra.”

“Nope, it’s all covered by your membership”

It turns out unlimited towing actually means $2500 worth of towing. I should have known this, but I’ve never studied the details of my membership. Naively I took the name of the policy – “Unlimited Towing” at face value. Nothing is unlimited.

On the way to Sister’s Creek Dock, while in the channel, we run aground again. I’ll never use this section of the ICW again. He quickly pulls us off and we continue until we see the other towboat coming from the south and he transfers me to the new boat.

We get to Sister’s Creek Dock and maneuver my boat, with the help of a couple from a trawler at the end of the dock, backwards into the only slip on the land-side of the dock, where I tie off and then sign off on all the paperwork.

Now I’m back on my boat making a pot of peppermint tea while putting on my wetsuit. I have to get in the water and try to push the propeller shaft back in the boat. I get out the ladder and hook it to the starboard rail. I pour a cup of tea in my coffee cup and pour the rest in an insulated travel-mug with a lid. I’ll drink this after I get out of the water. It’s a bit chilly out, but my wetsuit should keep me plenty warm.

After drinking the hot cup of tea, I climb down the ladder into the dark water. I usually look all around for alligators before getting in the water, but this time I don’t seem to care. Underwater the visibility is less than a foot, but I quickly find the propeller, which is jammed against the skeg, from which the rudder hangs. If the skeg wasn’t there, I might have lost the propeller shaft and taken on water very quickly. I try to push it back into the boat, but to no avail. I remember the plug. I climb the ladder, dry off a little, go below and pull the wooden plug out of the prop-shaft tube, get back in the water, brace my feet against the skeg, and successfully push the shaft back into Sobrius.

When I climb back into the cockpit, I sip my hot cup of tea from the insulated travel mug as I take off the wetsuit and dry off. Now I have to try to fix this problem, or else I’ll be trying to sail all the way home with no engine, which would be extremely difficult, mainly on account of the Main St Bridge, which only opens five times a day and usually has a strong current going one way or the other, depending on the tide.

The prop-shaft coupling, which holds the shaft to the transmission, has a set-screw that holds the shaft in place. The shaft and the coupling are, I think, supposed to be hammered together, then the set-screw just provides extra friction. But my shaft slides in and out freely. The set screw, I find, has been sheared off and is hollow. I can see light through it when I shine the flashlight into the coupling. I have extra set-screws, provided by a previous owner, and I try my hardest to remove it, but it won’t budge. I make a cheater bar out of part of the swim ladder, but still it won’t budge. I have to think of something else.

While waiting for a solution to come to me, I decide to make a new key for the coupling. This is just a rectangular piece of steel that fits into slots cut in the coupling and the prop-shaft. I have a piece of stock in the navigation table. But I can’t find a hacksaw. I should have brought my Makita 4” grinder, which would make short work of the job. Instead I ask Gordon, my neighbor in the trawler, if he has a hacksaw that I can borrow.

“I have a little one, but it’s not much good for anything.”

“Well, if it’s not too hard to find I’m willing to give it a try.”

He returns to his boat and emerges soon after with a mini-hacksaw. I successfully use it to cut a piece of keystock, which I then shape with sandpaper, rounding the corners. After about an hour of work, it fits in the slots, and I re-assemble the coupling and prop-shaft.

An Idea comes to me and I get out my large bolt cutters and a small screw from my collection of old used screw and bolts. I select a small screw, cut the head off, and insert the headless screw into the hollow and frozen set screw. But it’s too long. I find another screw and decapitate it. This one fits. I put another set-screw on top of it and crank it down, hoping the set screw will force the headless screw into the prop-shaft and hold it in place.

Back in the cockpit I start the engine and put it in forward. Sobrius pushes against the dock-lines. I put it in reverse; Sobrius tries to move backward. All seems well now and I kill the engine and make dinner. I’ll try to leave in the morning.

Sleep is fitful. I’m kept awake by my thoughts. I’m doing math in my head, thinking about tides and bridge openings, debating about whether to try to sail home or to call for a tow.

Morning comes and it is cold and windy. The wind is NE at 15-20 knots and the tide is going out. I help Gordon and his wife pull out in their big and shiny trawler. We wave to each other as they pull away.

I stand staring at the outgoing tide. Its flowing in the direction I want to go, and if I leave soon I can make the 8:00 pm bridge opening. I get back on board and start the engine, turn on the instruments, and prepare the mainsail for smooth and quick hoisting, in case of emergency. The wind is trying to blow Sobrius away from the dock, so I’ll need help.

Some other sailors are standing on the dock and I walk to them, introduce myself, and ask for help departing. They readily agree. I untie all but two lines and my helpers hold them. I put Sobrius in forward gear and they hold us tight to the dock, against the wind, until I get going and then toss the lines aboard. It is 9:00 am when the strong current pulls us out into the narrow channel. A bridge is about 100 yards away. I back off slightly on the throttle so I can raise the main before getting to the bridge, but as I do, that same vibration ceases, and I know it has happened again. I throttle up, look at the water behind us, and nothing is happening. The prop-shaft has departed again, and we are swiftly drifting towards the bridge.

I release the mainsheet, push the boom out so it points downwind, and sprint to the mast where I pull on the mainsail halyard, hoping it goes up without snagging on anything. As the bridge and certain destruction approach, the mainsail goes up. I get back in the cockpit with just enough time to pull in the mainsheet, catch the ample wind, and steer us away from the bridge pilings and through the bridge channel. Within moments we are in the wide and deep St Johns River, and it feels great to be out of the narrow and shallow ICW. I relax a little.

I set the autopilot and go to the mast to raise the jib. The tide is going out and the current is fairly strong, but with both sails full we move upstream at 3.5 knots. With this wind we will be able to sail all the way to the Main St Bridge with only one upwind leg, which I hope we can tack through. On a broad reach, we pass a tugboat pushing a barge upstream. The current is doing a good job of trying to push them downstream.

I set the tillerpilot and call the towing company to upgrade my membership, anticipating the need for another tow at some point today or tomorrow morning. At a cost of $26, I feel like the upgrade is a fine investment. The bill I avoided yesterday was $1655.

The sailing is fine, and I take the reef out of the main. We are on a long straight leg, and I am hungry and cold. I set the autopilot and go below. I find a can of chicken-noodle soup. Perfect. I stick my head out of the companionway hatch and look around. All is clear. I fire up the alcohol stove and heat the soup, warming my hands in the process.

The soup is fabulous, and I eat it with a sleeve of crackers as the autopilot steers us up the big river. The barge I passed earlier passes to port, with plenty of room in the wide river. All is good and I am warmed from the inside.

We pass under a bridge with good speed, entering the upwind leg. The bridge casts a wind shadow, but we coast through it and catch wind on the other side before the current pulls us backwards. Ahead I see a dredging operation in progress on the left bank, while a huge container ship is unloading massive stacks of containers on the right bank. I anticipate a big wind shadow in the lee of the big ship.

We are sailing on a close reach towards the dredging, and I see that my depth gauge is not functioning. I can’t sail outside the channel without it, so I tack on the edge of the channel, right behind the dredging barge, and we immediately start drifting downstream. We are in the wind shadow of the big ship, and there is very little wind to catch as we try to sail across the river. But we are almost all the way back to the bridge when we reach the other side of the channel and have to tack again.

We sail back to the dredging barge and tack. We sail back to the bridge. The barge, the bridge… this goes on for half-a-dozen tries. I am patient and I know the tide will eventually turn around and be in our favor.

But now a big white tugboat is coming downstream. I have to avoid it while tacking. I try to estimate when it will get to me, and tack accordingly. It passes without incident. But behind it is an enormous container-ship, also coming downstream. I really have to stay out of its way. I short-tack until it passes, trying to remain calm, and it too passes without incident. Of this I am thankful.

I lock off the tiller with the tiller-tamer and go below to switch the depth gauge off and back on, hoping this makes it work again. It does, so now I sail a bit closer to shore behind the dredging barge, and then closer to the dock in front of the bridge, but still we make no progress.

Finally I get another idea and sail very close to the dock on the right bank, in front of the bridge. I quickly get on a very close reach, pinching into the wind, and try to stay as close to shore as possible, hoping that there is an eddy behind the big ship. This time we are just a bit further upstream when we reach the left bank, alongside the dredging barge instead of behind it. I get very close to the barge before tacking again, and I can feel the difference immediately. We have wind and the close reach points us up the river instead of across it. We’re going to make it this time!

I am able to point upstream and sail on a close reach without having to tack again before turning to port, a bit less upwind. I let the sails out a little and we accelerate slightly.

Ahead of us the river stretches long and wide, and the wind has decreased. I go below and get out the genoa in the black back bag, carry it up on deck, and proceed to change sails while underway. The autopilot does a fine job of steering us up the river. I stash the working jib in its yellow bag, and we sail along now at 4 knots instead of 3.5, speed over ground. The current is still against us.

The sun is now setting in front of us, over the right bank. The sky shows us all of its warm colors before turning black, and the last bridge before Main St is in view. The current has switched as the tide is now coming in. Anchorage Area A is just on the other side of the bridge and I will stop there and make a decision. I don’t want to try to sail under the Main St Bridge without the engine, because the current will be pulling towards the bridge at nearly three knots, and the wind has died considerably. In addition, there are two more bridges to pass under, one of which is a train bridge that sometimes closes, and there will be big wind shadows to deal with. I either need to fix the prop-shaft or wait until morning and call for a tow.

I pass under the bridge, steer to the left bank, leave the channel, and turn Sobrius around to face the wind. I go forward and pull out the anchor. We are in Anchorage Area A, as indicated on the chartplotter, and I lower the anchor into the water as we slowly drift into the wind. But as I do I see an old crab-trap buoy right under the bow. The anchor keeps falling, further and further. It’s way deeper here than I expected, like 50 feet. There’s nothing I can do about the crab trap. I hope the anchor doesn’t snag it.

With the anchor set, I go back to the cockpit and assess the situation. I make a pot of tea and decide that I will need to get in the water at some point anyway, so I should go ahead and do it now. I put on my wetsuit and sip hot tea. I think of my sister who recommended the peppermint tea, which brings me comfort now.

I get in the water, brace my feet on the skeg, and within seconds the shaft is back in the boat, and I am soon back in the cockpit.

Another idea comes into my head. When I was a mountain-biker, we always carried electrical tape with us and used it to fix our bicycles when nothing else would work. Lots of rides were saved by electrical tape.

While laying on my side on top of lifejackets in the port quarter-berth, I clean the prop-shaft and coupler with paint thinner, dry them, and let them sit for a minute to completely dry. I lift the engine slightly and insert the prop-shaft into the coupling, at which point I notice a loose motor-mount nut. I go find a wrench and tighten the nut. This must have been part of the problem. Then I take rigging tape and try to stick it to the shaft, as a test, and it really sticks well. Very tightly I wind almost the entire roll of tape around the shaft and the coupling, firmly joining the two. With a little more tape, I wind a bit around the shaft just in front of the shaft tube, where it exits the boat, to stop slippage should it occur.

Back in the cockpit it is 7:00 pm, one hour before the next scheduled bridge opening. I start the engine, let it warm up, and put it in forward for a moment, then back to neutral. I go to the bow and look at the anchor rode, which has slackened. I go below and look at the prop-shaft. Everything looks good. I test it again, first in forward gear, then in reverse. Still the shaft looks good. I radio the bridge.

“Main Street Bridge, Main Street Bridge, sailing vessel Sobrius.”

“This is Main Street Bridge, go ahead Sobrius.”

“We are inbound and requesting passage at your next scheduled opening.”

“Our next opening will be at 8:00, please be in front of the bridge ten minutes prior and we’ll get you an opening.”

“I’ll be there, thank you.”

“Main Street Bridge, monitoring 09 and 16, out.”

“Monitoring 09.”

Now it is time to pull the anchor up, and I put Sobrius in forward at idle-speed and go to the bow. I have about 250 feet of rode out, and I begin pulling it in, which is very difficult in the current. Then it really becomes difficult. The anchor is snagged on something, probably a crab trap, I think. I go to the cockpit and throttle up hoping to break the anchor free, then put it back in idle, go back to the bow, sit down, brace my feet, and pull as hard as I can. The anchor feels like it breaks free, but is still extremely difficult to pull up. I drop it, letting it fall back to the bottom, hoping to dislodge it from the trap that I imagine is there. Then I begin pulling again. Finally, the resistance ends and it starts coming up easily. I put the anchor on deck, but not away, in case I need it again. I also have the stern anchor hanging off the stern pulpit, in case of an emergency, like drifting towards the bridge without power, like I was this morning.

We motor around in a couple of circles within the anchorage area, and again I check the prop-shaft. Nothing has changed. I plan to motor around while waiting for the bridge, without decreasing the RPM’s. I also raise the mainsail, for extra power and safety.

It is 7:50 pm and we are 200 yards from the bridge, pointing away from it, into the current, sitting still. To my left I can see down a street. To my right is a sidewalk in front of a building. I notice that the water-level of the river is almost as high as the sidewalk.

I hear a horn behind me, signifying the beginning of the bridge-opening sequence. I turn and look. Lights are flashing and traffic is stopped. No other boats are out here tonight. The enormous bridge is opening just for me. I feel special as I pull on the tiller and we start moving down-current, and I thank the bridge operator with the VHF after safely passing under.

We pass through the train bridge, then under I95, and the river widens as the lights of Jacksonville fade into the background. We catch a bit more wind, and with the current, the main and the engine we are making five knots. I could rev the engine quite a bit more, but I’m happy with five knots. At this speed we will be home in under an hour.

We get to the red buoy where I can safely turn west, towards the Ortega River, and I get out the spotlight and engage the autopilot. I stand on the bow looking for crab traps, just as I did on Sunday morning. It is now Wednesday evening, one day later than scheduled, but we are almost home, and a sense of peace is coming over me. I’m very happy to be under my own power and almost home.

I see a white buoy directly ahead, and I return to the cockpit, remove the tillerpilot, and steer us to port, around the crab trap, then return to the bow.

I can see the red and green lights from the buoys marking the entrance to the Ortega River, and I lower the mainsail. Soon we are in the Ortega river, and I pick up the radio.

“Ortega River Bridge, Ortega River Bridge – sailing Vessel Sobrius”

“Go ahead captain”

“We are inbound, slowly approaching, and requesting an opening.”

“Keep on coming in and I’ll get you an opening started shortly. This is Ortega river Bridge, monitoring channels 09 and 16.”

“Thank you, monitoring 09.”

The little drawbridge opens and we pass through without having to slow down. The Marina at Ortega Landing comes into view to starboard and I set the autopilot, go forward, and put out three fenders to port and one to starboard. I move one end of a long dock-line from the starboard bow to a cleat in the cockpit. I move another from the starboard stern to the same cleat. When we get to C Dock, I slow us way down, turn us to starboard, into the dock channel, and starboard again into my slip. An angled dock-line that I left tied to a piling and a cleat on the dock catches the bow as I step off with the two dock-lines in hand. I tie them off. Sobrius comes to a stop. We are home.

Reviewing the journey, I learned many things. First, I should have studied the ICW more thoroughly and probably should not have taken it home. I should have had the turnbuckle taped up so it wouldn’t catch the jib-sheet. I should have been running the engine while crossing Nassau Sound so I could use it if needed. I should have replaced the prop-shaft coupling with a split coupling last year, when I first noticed the problem. I need to align the engine with the prop-shaft; having to lift it in order to insert the shaft into the coupling indicates that it is way out of alignment. And I should have brought more tools.

Finally, I am very grateful for this journey and all the difficulties I encountered. A trouble-free journey would have taught me nothing, and only delayed the onset of the prop-shaft problem. Since I plan to go to some of the remote islands of the southern Bahamas this Spring, I might have encountered this issue there, where I would be unable to fix it properly, or worse, I might have run aground on a remote reef.

Problems, difficulties, and challenges teach us and make us better at what we do. They make us stronger, better able to cope, and at last, they give us good stories to tell.