In the Ward

We stand behind the closed, metal door of the psychiatric ward on the eighth floor. Tanya tells me we must ring the bell to announce our arrival, and we do. A voice asks us who we are. Tanya announces us and a few minutes later a heavy nurse with a round ring of keys opens the door to let us in. I’m very curious and a bit afraid of what I might see. The corridor going to the nurses’ office is long, and the walls are bare. The patients’ rooms are all on one side of the corridor and on the other side are offices, the dining room, the recreation room, and so on. The patients’ rooms are rather small, each with a window and a narrow bed with white bedding. Some rooms have two or three beds. The rooms are mostly empty now, since all the patients are walking around in the long corridor.

The corridor of a mental ward is a significant place for the patients: they all walk around in silence, alone, yet somehow together. There is a certain pattern and harmony to their steps and in their obvious, yet invisible, interaction with each other. No-one passes anyone else. The patients coming do not acknowledge or notice or care about the patients going. They walk like they are all in absolute darkness, holding tightly to an invisible rope, as if they might fall and never be able to get up again. Or they may even get lost and never be found again. It could be that, walking up and down the corridor all day, they are trying to organize their minds and calm their thoughts, which consume them with the untamed energy of despair.

I can’t help but notice a huge woman walking down the middle of the corridor. She has covered her hair with a white sheet and a large bandage hangs loose from one eye, although there doesn’t seem to be anything wrong with it. Pinned to her chest is a large piece of paper, on which she has written all the rules she thinks everyone should obey: “You must be good; you should not lie; you should be clean”, and so on. She even reads them aloud as she walks, pointing accusingly at the nurses who pass by.

We go to the Head Nurse’s office and pick up the key to the recreation room. Inside, it is cold and empty, except for a long rectangular table and a number of wooden chairs. Everything is light blue and gray. The room seems bored, yawning and dreaming of something new and exciting. The windows are large, and light comes through them like a familiar guest accustomed to dropping by any time, inviting itself in and sitting wherever it likes. There’s a sink on either side of the room, a very large roll of paper, and a closet full of paints, brushes, markers and colored pencils, along with files for the patients’ art work.

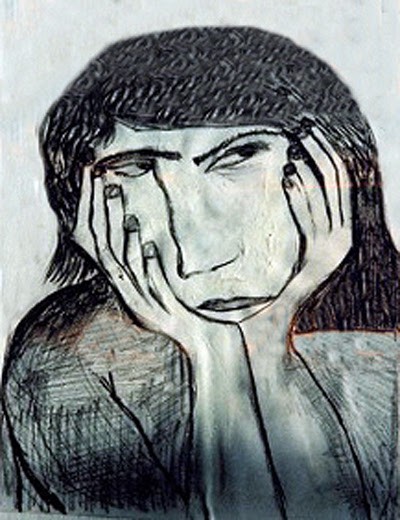

We lock the door from the inside to give ourselves time to set up. We lay the paper, brushes, paints, and everything else on the table. When all is ready, the patients arrive like prisoners at a concentration camp: pale, silent, sad, disoriented, without a shadow of hope in their eyes or a drop of joy in their hearts. I ask myself whether any of them has smiled in the past few days. I believe one can go without food, but not without joy. I can easily see in their sad eyes that they’re already starving.

They come in single file, like innocent, helpless children lined up for a field trip. They are quiet, vulnerable, obedient. They seem to trust everyone but themselves … they’ve long since lost faith. They are no longer citizens of this world but live in a world of their own creating.

Sitting meekly on the edge of their chairs, the patients look around without focus. Perhaps life lived in a hospital becomes one endless, deadly boring day, spent walking around looking at gloomy colors, smelling the scent of medicine, and looking at the other patients hanging at the end of their rope. Who is to say how hungry they might be for bright colors and the chance to walk down the street in the sunshine again, feeling perfectly healthy? Are they perhaps longing to desire again, to desire life with everything in it, longing to bite into it hard and swallow it in one gulp?

As the patients are all sitting down, one man suddenly points at a young woman sitting in front of him and says: “Look at her: she’s pregnant! She’ll be giving birth any day now, and I am going to be there in the delivery room witnessing everything!” The pregnant woman protests: “No way! You can’t come to the delivery room. What are you, crazy?” But the man is staring at his drawing now, ignoring her completely, mumbling some words under his breath that I can’t make out.

Drawing

Sitting next to the pregnant woman is another woman, with a skinny face and long, straight, greasy hair. She looks terribly down and depressed. I push the colors toward her and ask her to show me what she likes to draw. She stares at me for a while, then stares into space, then stares at me again, this time like she knows just what she wants to say… yet she doesn’t say a word. Instead, she draws a pretty, geometric house and garden with long-stemmed flowers and trees in neat rows. Everything is precise, neat and orderly. The lines are strong, sure and defined. There is a large sun dominating the scene like a child’s drawing. It is clear that she wishes to be happy.

Suddenly, the pregnant woman jumps up from her chair and waves her drawing at everyone. “Look!” she exclaims with joy. “Look what I’ve drawn, everyone!” Her drawing is a jumble of confused, tangled lines. I say, “Wow, you did well!” But she explains that this isn’t really HER drawing: the unborn baby in her tummy did it. “Yes, my baby already knows how to draw and how to color.” Then she collapses back into her chair in exhaustion and stares out the window, for a while just lost in her thoughts, before continuing to let her baby draw and color.

I’ve brought chocolates and cookies for the patients, and Tanya has brought muffins and all sorts of poetry books. I have also brought a book of Pablo Neruda’s poetry in the original Spanish and in English. When he sees this book in my hands, one young man with a beard and mustache can’t wait to read one of the poems in Spanish. He reads beautifully and passionately. When he puts the book down, everyone applauds. Quite encouraged by this, he says, “Well, you know, by the end of the hour I might even sing for you.” After a few minutes he does so, getting up to sing as if he were in a grand opera hall performing before hundreds. Ending his performance, he bows formally and thanks his audience. He is dramatic and has a good sense of himself. When he finally sits down, he says he’s only sorry he doesn’t have his guitar to play for us. He is obviously happy with the attention everyone has generously given him.

We all have such a good time that day. One boy, perhaps only sixteen or seventeen, and short and round as a dumpling, follows us everywhere. Whenever someone asks his name, he innocently raises his ID wristband to his eyes and reads: “Juan. That’s right. Juan is my name.” And every time we smile.

The patients here are male and female, young and old, black and Hispanic. They are all brought in off the street, most often because they have created some kind of disturbance and complaints have been made. But they all have things in common: they are poor, dirty, lost, and drowning in their own pain. They will only be kept in this county hospital for a maximum of two or three weeks — just long enough to force them to take their medication and get them halfway balanced. Then they are out the door… to make room for new patients.

A New Pair of Shoes

A new patient who walks into the room that day is tall and skinny. Even his eyes are slim and slender. They are very blue … and also very red, as is the skin around them. He goes directly to Tanya and points to a large box of assorted old shoes stored high on a shelf. He asks her if he can try on a pair. He explains that he lost his shoes while being dragged in here, and he’s been walking around in his socks ever since. He says when they brought him into the hospital he had been walking around Venice Beach for days before finally collecting the last bit of sense he had and calling the rescue line. “Yes, ma’am,” he says to me, “I called because I needed assistance badly. I collected my last drop of energy and told them, ‘come and get me, I need help’”.

We bring down the box of worn-out shoes. All the male patients leave what they are doing and gather around the box like pirates around buried treasure. They look at the shoes with amazement and excitement. Then they all sit quietly around the box like well-behaved boy scouts, waiting their turn. Once each has found a matching pair, they start walking around the room trying out the comfort and joy of a new pair of shoes. On seeing this, a nurse, just leaving the room, stops and turns back as if deciding whether it can be allowed. “Just take all the shoelaces out. You know the rules: they aren’t allowed to have shoelaces in their possession.”

Steve, the tall, skinny man who discovered the shoes in the first place, sits apart from the others, dignified and silent, watching everyone try on shoes. He looks at everything and everyone without any hope in his eyes, as though shoes are not all he needs. God knows how much more, I think to myself. God knows where he will end up sleeping and who he will end up being when he gets out of here. After the others claim their shoes, Steve tries on all those that remain in the basket before leaning back in his chair in disappointment. “It’s the story of my life,” he sighs. “Nothing fits and it’s my own fault: I have the largest feet in the world. I wear a size 13.”

We’ll Wake Up In Heaven

Nancy is the woman with the skinny face and greasy hair, the one who drew the pretty house. She continues to draw, just like a kid, this time adding next to the house a road and a basketball hoop. She says she misses her family badly. She says she wants to go home soon so she can braid her brother’s hair in the morning before going to school. She says she wants to make her favorite pancakes.

She says it all came to her when her young son died in her arms. “Girl,” she says to me, “I just went crazy. Yes, my little boy is the only reason I’m here.” She says: “Everybody gave me the crap talk, about how we’ll all die some day and wake up in Heaven with God and all that, but it didn’t help me a bit. When he died, it burned here in my chest so bad I just couldn’t take it. And that’s the reason I’m here today.” She puts her head down on her drawing and remains there for a while. I can’t tell if she’s crying, if she’s passed out, or what. Then she sits up, straightens her hair, and smiles. But it is a meaningless smile, revealing nothing more than a few missing teeth. I wonder what her real story is. I wonder how she lost those teeth.

Suddenly, Nancy gets up to leave the room, taking a large sheet of paper and a few colored markers. She says she wants to make a birthday card, for her brother whose birthday happens to be next week. I tell her she can take the markers with her, and she seems happy. She explains that it gets so boring being here all day long with nothing to do. She shakes my hand politely and thanks me for the cookies. “But next time try to bring some grapes, please,” she adds as she walks out. “I just love grapes…”

As Nancy is leaving, a nurse is coming in with a tray of medicine. Seeing the markers in Nancy’s hands, the nurse shouts: “No paint or markers out of this room, please!” Then, passing by, she bends towards me and says: “We don’t want the walls of the ward covered in graffiti.”

At the end of the day as I’m leaving, I see Nancy sitting near the wall in her room with her head in her hands. Her tangled hair covers her face. I don’t know what she is doing there, frozen like a statue, but above her head on the wall I can see there is something written in colored marker. It reads: ‘Nancy was here’.

Tags: Art, Dear Dr. B, Encounters of a Volunteer in a County Hospital, Healing

Posted in Literature, Mahvash Mossaed |

Originally published at mahvashmossaed.com on March 19, 2017.

Originally published at medium.com