“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.”

So (allegedly) said Socrates. If the attribution is correct, it would appear that even the ancients participated in the time-honored tradition of older generations complaining about the young. What is perhaps most striking about Socrates’ complaint is how modern it sounds. His accusations—that the young lack manners, disrespect their elders, talk foolishly, and love luxury (as opposed to honest hard work, presumably)—could well have been said by any older person today, perhaps while shooing the young off their proverbial lawn.

Consider, for example, common criticisms of Millennials and Generation Z—the age cohorts born in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. They have been accused of entitlement, oversensitivity, and lacking a robust work ethic. These accusations are variations on old themes. It is perhaps as inevitable as the changing seasons that generations eventually grow up, look to the young, and ask “Are the kids alright?”

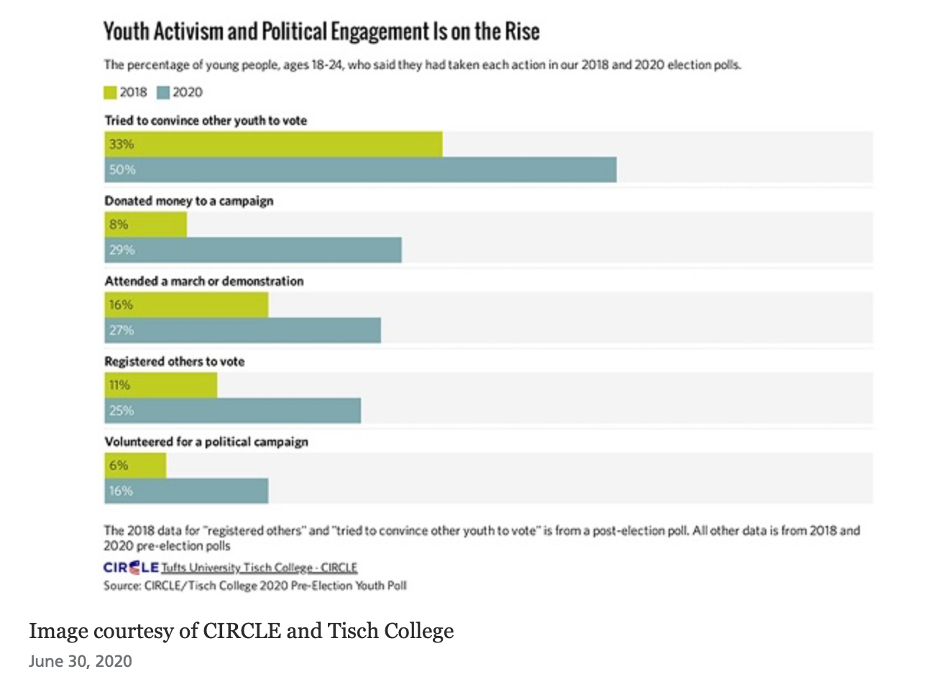

Yet it is not just the older generations who criticize—the younger generations also have their say. This can include the standard criticism the young tend to have of older generations—that they are out-of-touch, that they are overly conservative, that they have been reckless with the world they inherited and now must pass on. But the young also speak out in other ways. In recent years, we have seen younger generations raise their voices on behalf of shaping a better world. The young have taken a leading role in calling for changes to how we engage with issues of climate, racial justice, gun violence, inequality, and more. They have marched, voted, and participated in the public conversation towards the goal of radically reshaping our society. This engagement has grown by quite a bit. Taking just the example of electoral politics, there was a significant uptick in youth engagement in the 2020 election compared to the 2018 election. Following the 2018 election, 33 percent of youth reported attempting to convince their peers to vote, and 11 percent reported registering new voters. Months before the 2020 election, 50 percent of youth reported attempting to convince peers to vote, and 25 percent reported helping to register voters.

This increased engagement appears to be, in part, a response to the perceived shortcomings of previous generations in creating a better society. This is particularly true in the case of climate change, where the actions—or, more accurately, the inaction—of prior generations have contributed to a crisis that threatens the health of the entire planet. There is a sense among younger activists that much of their task, then, is to clean up the mess left by those who came before, and this sense underlies the dialogue between the more political members of the younger generation and their elders.

Given these dynamics, and their relevance to how we address issues of core importance to health, it strikes me as well within the purview of this column to tackle the question of whether the kids are indeed alright, and how the extent to which they may not be alright reflects a broken status quo around issues that matter for health.

All of us—younger and older—live in a world that is evolving, complex. This reflects a range of fast-moving changes, from the emergence of new technologies, to the advance of social movements, to sudden shocks like political disruptions and the pandemic. Those of us who are old enough to remember what the world was like before this moment are perhaps more apt to fear what all these changes might mean for the future. This fear can cause us to miss the opportunities of the present, the chances that arise urging us to envision a world that is not only better, but radically so. Those who are younger lack this experience of prior context—this moment of change is their primary reference point in life. They are native to the transitions we see. This can give them the capacity to notice the opportunities older generations can miss, and to boldly seize the chance to shape a better world.

This boldness can, of course, have drawbacks. The zeal to shape a better world can at times lead to devaluing what is good about the world we already have. An evolving moral consciousness can inform a willingness to cast aside much that is useful and necessary from the past. And impatience to get to a better world can cause us to neglect core liberal principles in our rush to end injustice. These are mistakes to which we are all susceptible, but the young are arguably at greater risk. They have had, on balance, less exposure to the consequences which can come with pursuing, with maximum certainty, ideas that may be partially formed or wrong. The corrective to this is, of course, experience, as well as the presence of mentors to help the young channel their conviction into an engagement with the world that is fundamentally constructive. Far from being pedantic, this engagement is good for all participants. It gives the young access to valuable advice, and it keeps their elders in dialogue with the future, via those who will one day shape it.

Such a dialogue strikes me as the most effective way of ensuring that the kids—and older generations—remain alright. Fundamentally, we are best served by a balance of generational perspectives. By striking this balance, the generations can maximize their strengths and minimize their vulnerability to pitfalls. Those who are younger can help those who are older better see how the world might be changed at the structural level, by creating a new status quo, one that is more supportive of health. And older adults can help the young to recognize that, in our pursuit of positive change, we need not reinvent all that has come before—we can draw from the best of past traditions to support an ever-better future.

This balance intersects with the broader project of pursuing a healthier world within a liberal context. The excesses of the younger and the older, if unchecked, can both lead to forms of illiberal thinking. Those who are younger can be captured by a zeal to rearrange systems, causing them to throw some rather necessary babies out with the bathwater. These include core liberal norms which can look, to the young, like reactionary roadblocks. Older populations, for their part, can, in their fear of change, run the risk of embracing some genuinely reactionary, illiberal notions. These can align with political movements which seek to make the future merely an image of the past. Conversation between the generations, unfolding in a liberal context of respect and civility, can help us avoid these excesses and perhaps even open the door to greater wisdom for everybody. Such conversations also allow older generations to welcome the young into the fold of engaging with the issues and responsibilities that constitute the pursuit of a better world. This makes teaching, in particular, a privilege, for the opportunity it affords to participate in this conversation. Yet as we teach, we should embrace the fact that there are indeed times when society is well-served by learning from the young, by following their lead. Theirs is a unique and valuable perspective, from which all generations can benefit.

Before concluding, I should note, by way of full disclosure, that, in addition to being Dean of a school of public health, a position which lends daily perspective on the rising generation, I am also the father of two Gen Zers. This has admittedly instilled in me a bias in favor of the younger generation, well-positioned as I am to see their commitment to a better world and to recognize how their critique of past generations is in many ways correct. At the same time, being a parent underscores how those who are younger, however engaged they may be, are still, well, young. There is much they have yet to experience, and this lack of experience can inform a lack of the hard-won wisdom that only comes through years of living. For this reason, it is not responsible to say we should be led by the young in all cases, only that we should listen, always, to the perspective of those who are younger, as well as of those who are older, and not patronize nor condescend to what either group has to offer in our shared pursuit of a better world.