I am a recovering opioid addict. I once went to the dentist because of an infected tooth, a common occurrence normally treated by antibiotics. Instead, I persuaded the dentist to pull three perfectly good teeth in order to get one prescription of 30 Vicodin—taken in a single dose before I’d even left the pharmacy. I was so addicted to Vicodin that I needed a constant level of opioid in my system just to function, and I kept myself going in four-hour increments. Three teeth seemed a small price to pay.

I come from an affluent family. My father, Sam Coslow, was a composer and movie producer who won an Academy Award for producing the 1943 short film Heavenly Music. He followed his early show-business career with a more lucrative career in finance, after founding a stock market newsletter called Indicator Digest. I had a beautiful and witty mother, Frances King, who had parlayed her opera training into a cabaret act during New York’s Cafe Society era, regularly performing at the Manhattan restaurant One Fifth Avenue. I grew up in beautiful homes in Miami and Bronxville, N.Y.; spent my summers in London and Florence; and got an undergraduate degree in English from Sarah Lawrence College. I was not supposed to end up a drug addict.

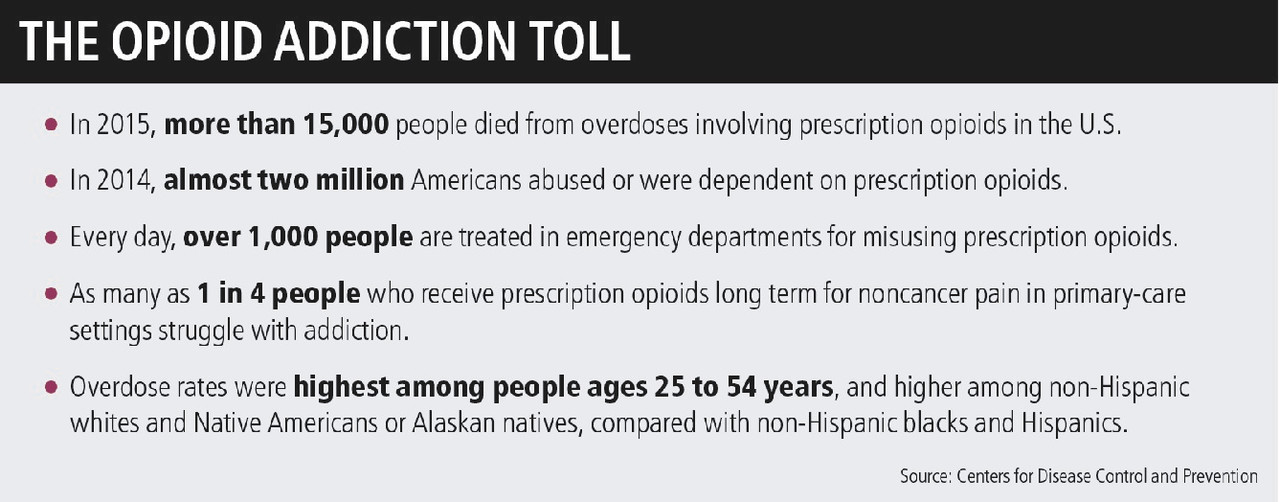

If you, your child, or spouse has a drug problem, know that your family is not alone. A scourge is upon our country. Nintey-one people a day die from opioid overdoses, almost quadruple the rate in 1999, calculates the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That means 300,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses from 1999 to 2015, with middle-age adults being the most vulnerable. President Donald Trump has just ordered a special opioid-crisis commission. Many consider this to be the worst drug crisis the country has ever known.

Now, looking back, I see there were some early red flags. I had been a panicky child, plagued by a severe case of separation anxiety from my mother. This was the 1960s: A bit of tranquilizer was considered a good way to get me to school. By the time I was in my late teens, I was addicted to downers. Cocaine and booze followed, but I found the 12 steps and stayed sober for many years, until the pressures of my budding Hollywood career produced a series of headaches.

My opioid addiction began with a single prescription for Vicodin, prescribed for my migraines. I was in my early 30s and head of casting at Carsey-Werner, one of the most successful television-production companies ever. I oversaw the casting of Roseanne, Cosby, and That ’70s Show. I was nominated for an Emmy and discovered Ashton Kutcher. I had all of the material prizes: a six-figure salary, a companypaid $100,000 car, and a beautiful home in Encino, Calif., which I spent a year meticulously renovating.

Cara Coslow

I had no idea that these drugs, prescribed for legitimate pain, would end up taking everything but my life. I liked the way they made me feel. Vicodin was the best antidepressant I’d ever known. These pills gave me energy and spunk. They gave me the qualities I wanted but couldn’t manufacture on my own.

I went from filling these prescriptions monthly, to twice monthly, to weekly, to doctor-shopping to come up with a prescription for 30 pills every day—the amount I needed to function. The opioids no longer made me feel good; without them, I suffered almost unmanageable pain. It felt as though I had tiny coal miners with tiny pickaxes living in the center of my bones and scraping to get out. I’d sweat profusely, have diarrhea, and vomit. So I endured surgeries and injuries and tooth extractions for the next handful of pills. Opioid withdrawal is a pain like no other—it will bring the toughest stevedore to his knees.

By 2000, I was putting in only brief appearances at work. My days instead were spent going from the emergency room to urgent care and from doctor to dentist in an ever-widening radius. You couldn’t see the same doctors too often, or they’d know you were seeking drugs. I faked injuries or inflicted them on myself, and ran an elaborate con game on the medical community. Glancing at a photograph of a teen behind a doctor’s desk, I’d say, “Is that a photo of your son? Why, he’s good-looking. Has he ever thought of…acting?” I’d practically promise to make the kid a star.

I awoke one Christmas morning in acute withdrawal, desperately needing more pills. I was due to spend the day with friends and their child, whom I adored. But by then, I had used up all of the neighborhood medical facilities and was seeking drugs on the outskirts of town, at shabby clinics that needed my cash. But because it was Christmas, I bolted to an emergency room in Malibu—something more festive with a view of the ocean. I was very sick when I got there. I’d learned from a doctor, who was also an addict, how to fake an embolism or a heart attack and ensure my place at the front of the ER line. But that amount of drama was pointless. I needed to get in and out for Christmas dinner.

I got 10 Vicodin—not enough to get me out of withdrawal. I went to dinner, sat there in misery, and as soon as it was done, I was out the door to an urgent-care facility in El Segundo. Again, I got a dose too small to relieve the pain.So, I burst into my third ER, at a proper hospital, complaining of chest pains, sweats, and other coronary symptoms, a couple of them genuine. It didn’t matter that this was Christmas; I’d been living the same day for the past several years. Only with a shot of Demerol, administered at midnight, was I finally able to sleep.

The nightmare lasted for 10 years. Along the way, I lost my entire fortune—my jewelry, my furniture, my 401(k), my art, and the collection of letters written by Colette, George Sand, and Victor Hugo that I’d purchased in a small store on the Rue du Bac in Paris. I literally lost millions of dollars, some of it in future earnings but most from the compromised logic of a drug-addled brain, like quitting my six-figure dream job and walking away from property I had invested heavily in.

But it’s also important to note that I got hooked on these pills in the late 1990s—a crucial time in the history of this crisis. Suddenly, opioid medications, which had been used primarily and legitimately for acute pain that came from injuries, surgeries, or palliative care, were being prescribed liberally. In Drug Dealer, MD, Dr. Anna Lembke describes the influence of Big Pharma on the prolific prescribing of pain meds that started in the ’90s. Companies like Purdue, the manufacturer of OxyContin, funded lectures, conferences, and research that promoted the use of these drugs for nonacute pain.

From 1999 to 2009, I tried to get clean some 20 times, including checking in and out of 10 acute detox wards and rehab centers, the rest at home with nurses and doctors. I couldn’t stay off the drugs. The postacute phase of detox was so miserable that I invariably went back to opioids. I tried methadone and found I couldn’t function on it. I nodded out. Too zonked to make good casting decisions, I was excluded from important meetings at work. Too ashamed to tell my bosses how much I needed help, I asked to be let out of my contract.

Later, I tried Suboxone, the other drug substitute used in medication-assisted treatment. But I also abused it, never sticking to the prescribed dose. If getting off opioids is an uphill climb, getting off replacement meds is Hillary Step, Mount Everest’s nearly vertical rock face. The withdrawal from methadone and Suboxone is torturous, protracted, and next to impossible.

The only time I ever came close to dying from drugs was when a detox doctor told me to stop taking methadone three days before he would perform an idiotic, highly dangerous “ultrarapid detox” procedure. It was neither rapid nor a detox. The third day off methadone, I was found almost unconscious on my guest-room floor after enduring the nearly unendurable pain of methadone withdrawal. At the hospital, I had to be administered drugs intravenously in the lobby—my blood pressure was too high even for transportation to a room. Methadone withdrawal is responsible for many documented deaths. If your loved one is hooked on opioids, please find a doctor who really understands opioid withdrawal.

Then, right before another Christmas in 2009, I got lucky. I met Dr. Mark Honzel during my frequent stays in the acute detox ward of Brotman Medical Center in Culver City. He was the big doctor there, and he intimidated me. He was a no-nonsense German, and I was self-important. We butted heads, and he made me cry. But, by this point, I was living half a life, with no career and very little money. Recovery was my only real option, and I knew Honzel was the one doctor I could trust. I had overheard him tell someone that methadone withdrawal is one of the hardest there is—no other doctor I knew had copped to that.

On Christmas Eve, he admitted me once again to Brotman. After two weeks, my insurance stopped paying for the detox. Honzel said it was impossible for me to go home. I needed longer-care treatment, but my insurance wouldn’t cover rehab. Honzel had started working with a new rehab center in West Hollywood called Klean, a small and elegant facility close to my condo that would allow me to bring my dog Saffron, my companion who had ridden out 15 years of my ups and downs. But I was flat broke and I knew that treatment in private rehab facilities costs between $30,000 and $100,000 a month. Honzel arranged for me to get a Klean scholarship.

At Klean, I was looked after by a loving and nonjudgmental staff and wasn’t forced to continuously walk in the deserts near Palm Springs, as I had been at the Betty Ford Center. I stayed at Klean for three months. It was my route out, but there are, of course, other wonderful facilities around the country. If you need help finding a clinic near you, go to samhsa.gov, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration website, and type in your address. A range of facilities for all levels of care will pop up.

But if you or your loved one is trying to kick the habit, know that there are no shortcuts to getting off opioids. You just have to soldier through it. Because I had spent so long on Suboxone, it took over a year to get my energy up and even longer to feel OK in my skin. Honzel told me, “In my experience, relapse rates with opiate addiction are about 90% one year after abstinence-based treatment. It’s significantly better with medication-assisted treatment, but MAT is not right for everyone, and each patient has to be individually assessed.” I was one of those patients who couldn’t stay on MAT without abusing it, but ultimately I fell into the 10% who remained off all drugs. And now I am paying my blessings forward, working as an intake administrator for Klean, guiding addicts through the treatment process, and telling them what to expect. I haven’t taken a mood-altering chemical since I left. It has been more than seven years.

It’s a different life than I had. A better life—to be sure.

Originally published at www.barrons.com