In my professional work as a scientist, I have spent a lot of time in meetings. There were meetings that were very well organized and productive and others that regrettably were not. It was during these disorganized meetings that my mind would begin to wander. I found myself estimating the average salary in the room and the resulting cost of this meeting depending on its length. And then I sighed about the waste of money.

While focusing on money was an “amusing” diversion, it was not satisfying and didn’t last long. My mind continued to wander during these unproductive assemblies and I began to think about heartbeats. I had remembered that for most mammals, heart rate was inversely proportional to longevity. That is, across species, the faster the heart rate, the shorter the life span[1]. For example, the heart rate of a mouse versus an elephant as compared to their respective lifespans.

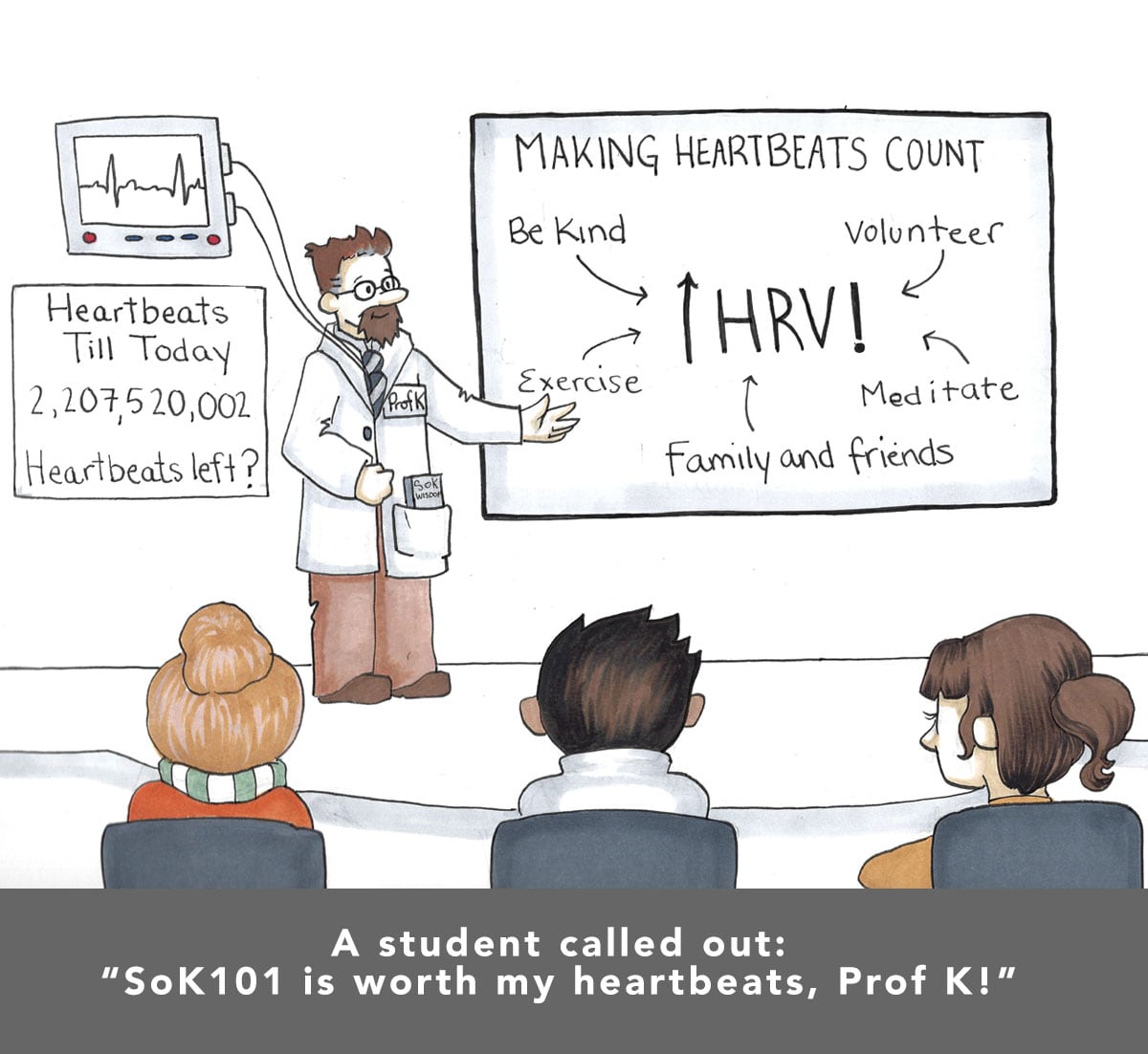

That led to a more personal consideration: if my average heart rate was around 70 beats per minute, sitting in that room for an hour cost me 4,200 heartbeats. That’s when this epiphany sank in. I was spending a very precious resource doing something without substantive meaning. Heartbeats are a personal metronome that Nature gave all of us to mark time. I realized that I had to spend my heartbeats more wisely.

THAT’S WHEN THIS EPIPHANY SANK IN. I REALIZED THAT I HAD TO SPEND MY HEARTBEATS MORE WISELY.

The heart is an amazing organ. If you think about it, we are walking around with a pump that circulates our entire blood volume approximately once every minute at rest (for an adult, roughly 5 liters). It works on demand; that is, it adjusts itself to our body’s needs. If we are exercising, bleeding, sweating, etc., our heart rate changes to keep providing blood flow to the rest of the body, especially the brain. It also adjusts how much force it will exert to meet those needs. An amazing variable demand-responsive pump.

In addition to exercise, stressors like anxiety or fear affect heart rate. These increase heart rate, a consequence of a shift in balance of the two major aspects of the autonomic nervous system: sympathetic and parasympathetic, which respectively increase or decrease heart rate[2]. This balance also affects something called heart rate variability (HRV)[3]. That variation is the time between beats. It turns out that lower variation in the time between beats is associated with worse health. People who have less variability have greater risk of death[4]. Diabetes, heart failure, and stress are all major causes of decreased heart rate variability, which make sense as they all have increased risk of death.

A way of thinking about HRV is the beat of a drum. A drummer can strike the drum exactly once per second for a total of 60 beats in that minute so that there is little or no variation between beats. Or the drummer can vary that—making it slightly quicker and slightly slower so that although there were 60 beats in that minute, the time between each beat varied more.

HRV is higher in younger people and progressively declines with age. Some consider it a test of aging. And while psychological stress and different diseases decrease HRV, breathing, particularly slow breathing, increases it. Many forms of meditation increase HRV, including compassion meditation[5]. That is extending kindness and compassion to others through thoughts has a beneficial physiologic effect.

EXTENDING KINDNESS AND COMPASSION TO OTHERS THROUGH THOUGHTS HAS A BENEFICIAL PHYSIOLOGIC EFFECT.

From ancient times, the heart was recognized as the center of emotion. Poetic expressions like “he wears his heart on his sleeve,” “follow your heart,” or ”a broken heart” points to how symptoms (what a person feels) around the physical heart probably reflected manifestation of different emotions like love and anxiety. In this model, the brain is the dominant feature telling the heart what it is perceiving. Yet the physiology is much more complex; it turns out that the heart has its own nervous system and provides feedback to the brain that can affect feelings as well as strategic thinking[6].

The heart also is affected by oxytocin (“the love hormone”). Released in response to different (particularly prosocial) stimuli like hugs or massage, oxytocin also directly affects the heart and cardiovascular system. In response to oxytocin, the heart in turn releases another hormone called atrial natriuretic peptide that can lower blood pressure[7]. Oxytocin appears to lower blood pressure and heart rate through other mechanisms, too. A physiologic way of saying that love is good for the heart.

Each heartbeat, therefore, is a reflection of a lot of complex interactions between our mental and physical states. And how our heart beats, in turn, affects how we feel. Beyond being a pump, each heartbeat is an important part of appreciating and living life. We feel love, suffering, sadness, joy, and amazement through it. We place our hand over it when expressing emotion or making a pledge. All because the heart allows us to feel the wonders of being alive.

LOVE IS GOOD FOR THE HEART. THE HEART ALLOWS US TO FEEL THE WONDERS OF BEING ALIVE.

Yet it is easy to forget about how precious each heartbeat is and take its continuous operation for granted. What if we changed that? How could we honor the gift of each heartbeat to attain greater meaning? It might show itself as gratitude for being alive and drive the focused pursuit of doing good with the limited number of heartbeats that we each have. And with my new-found respect for heartbeats, it is not just mine that matter—I also needed to respect everyone else’s.

After I realized the significance of heartbeats, I changed how I ran meetings. I would prepare extensively so that everyone would find the meeting productive, emphasizing a culture of listening to each other and openly seeking the truth. The result was really positive, likely because they found meaning through doing good work that honored their own heartbeats. Kindness here was motivated by the significance of heartbeats.

Of course, there are many other ways to honor heartbeats, not just through meetings. We honor heartbeats when we take care of ourselves (rest, exercise, eat well) and we take care of others (family, friends, coworkers, and strangers). And this does not mean that we should not watch a silly movie or do something that might be viewed as goofing off (that’s actually relaxing). It simply means that we should be more conscious of our heartbeats so that, overall, we spend them wisely.

Go ahead—feel your own heart[8]. Marvel at what you have been given. And then decide what you want to do to make the most of them. Their yours to make a meaningful life with.

In kindness,

David (Prof K)

[1] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23486438_Heart_rate_lifespan_and_mortality_risk

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autonomic_nervous_system

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heart_rate_variability

[4] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5900369/

[5] Kirby, J.N., and colleagues: The current and future role of assessing heart rate variability and compassion training. Frontiers in Public Health volume 5: pgs 1-6, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00040

[6] McCraty, R. https://www.heartmath.org/research/research-library/basic/heart-brain-neurodynamics/

[7] Grewn, K., and Light, K.C. Plasma oxytocin is related to lower cardiovascular and sympathetic reactivity to stress. Biol Psychol. Volume 87: 340-349 2011 doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.04.003

[8] You may do so by putting your hand over your heart or feeling your pulse at the wrist at the base of the thumb (don’t do so in the neck).