At many events like the one last night, I often have the least formal education of anyone in the room — including the busboys. I’m also often one of the youngest people there and one of the only ones who are female or from the middle of the country. I am definitely the only person there who was born into a house with no indoor plumbing, grew up skinning deer, and was driving big trucks and tractors by middle school.

When I talk about my company, I say that Frey Farms is a family business — which it is. But the words “family farm” usually provoke another round of uncomfortable questions.

First, people assume that I inherited the company: “A family farm? That’s great! Did your father put you in charge? Or did your grandfather start it?”

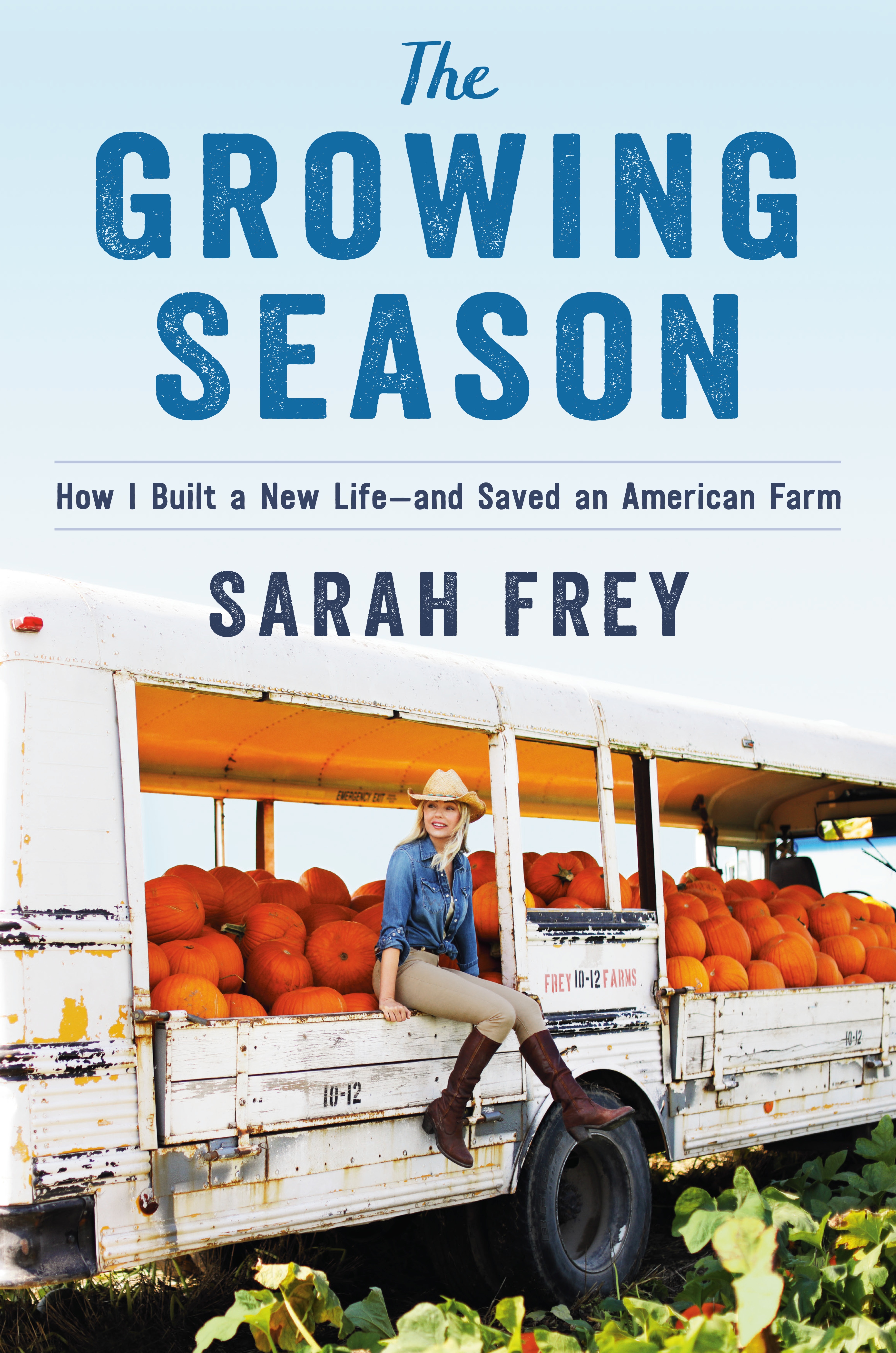

I understand how this assumption is made. I don’t exactly look like the image people usually have in their heads of a farmer— or a CEO, for that matter. On nights like this, I am frequently mistaken for someone’s wife. I come across, they tell me, as elegant and well- spoken, with a warm smile. What no one there knows is that on that very morning I was clad in grubby jeans, my unbrushed hair pulled back under a ball cap, yelling over the noise in the sorting room. No way I’d be mistaken for a Wharton alum.

How much should I share about my past and my family? That’s been a tough call my whole life. When people ask, “How many brothers and sisters do you have?” I might give the short answer: “I have four older brothers in the business.”

It’s not a lie. I do have four older brothers in the business. Sometimes I open up a bit more and say, “My mother had eight children.” This is also technically true.

“Yep!” I say to their inevitable astonishment. “I come from a big family.”

Rarely do I admit the full truth: “Including my half- siblings, I’m the youngest of twenty-one.” Yes, you read that right: twenty- one. In most rooms, it’s best to just talk about my four older brothers. They were, by far, the biggest influence on me. They taught me to hunt, fish, and live off the land. That knowledge gave me the confidence to believe that I could take care of myself no matter what happened. Those four know where I came from as no one else ever will.

Another thing people ask when they hear where I’m from is, “You’re from Illinois? I love Chicago!” “Chicago is a wonderful city,” I reply. But I’m actually from southern Illinois.

My home turf, Wayne County, is much closer to Kentucky than it is to Chicago. It has a culture, a way of life, and a mindset that are completely foreign to people who grew up on the coasts or in any major city. Where I come from, success is measured not by your educational attainment or bank balance but by the size of your truck tires, the speed of your four- wheeler, and the variety in your gun collection. In my part of the state, there are no street signs, no lights on the roads, no stores for miles.

As a child, I wanted nothing to do with our rural way of life. I couldn’t wait to grow up and move far away to a big city. I counted the days until I would leave our eighty-acre piece of rolling clay dirt in the middle of nowhere, what we called the Hill. For years I kept hoping my time there was over. I wished my childhood away. Some- times I didn’t think I would make it out alive.

Today I have a greater appreciation of where I’m from. Although we were dirt poor by most measures, in other ways we were rich. We had a piece of land, a big family, and freedom to roam in nature. We ate food we grew and caught ourselves. Ironically, that diet is now coveted and promoted as the ideal: clean, healthy, sustainable food, with nothing going to waste. We had the original farm- to- table lifestyle— we’d pull things out of the ground minutes before cooking them. We would take what we called “the ugly fruit” and turn it into the most delicious dishes and beverages. We were eating organic, hyperlocal, freshly prepared foods out of necessity long before it be- came a trend.

Because I’m one of the younger CEOs in my business circles, and my company’s founder, people often ask me, “How have you done so much in such a short period of time?”

The truth is, I started doing everything for myself early because no one else was going to do it for me. On the Hill, by the time I was seven or eight years old, I was doing things most teenagers wouldn’t even consider doing on their own, taking on projects that most adults wouldn’t venture. I do not advocate deprivation as a parenting strategy, but I can’t deny that, ironically enough, being disadvantaged gave me a huge head start. Even though I was sixteen years old when I founded my company, it was more like I was thirty-six, because of the lessons I’d already learned growing up where and how I did. By grade school, I understood how to take care of myself and the people around me.

That said, I do sometimes wonder what a normal childhood would have been like. And these days, given the choice, I’d much rather grow my food than hunt, gather, fish, or scavenge. As a result, I don’t always fit in back home. I can track an animal for miles. But I don’t like to do it just for sport. I’m a crack shot. But I’m not a member of the NRA. I know the woods and the fields like the back of my hand. But I prefer using Google Maps.

The one thing that I do not regret is how much where I come from made me love the earth. With every part of my soul, I love the soil, and I love owning plots of it. In that way, I am a typical farmer. It’s the farmer’s mentality to buy land and hold it, then buy more the second you can, even if it takes the last bit of cash that you have. The term for that is “land- poor.” Even if you can’t afford to do much with it, you don’t let go of that land, no matter what. Ever.

The land is part of me. I love the sounds of the countryside, the smells. The air in the country is lighter and fresher. The food tastes better. The water is cleaner. The sunsets are more colorful. You can see every star in the sky at night. I can’t even explain my connection to this land except to say that I need the feel of the dirt under my feet the way I need oxygen and water. Every American has agrarian roots. I don’t care how disconnected you might be from the earth in your day- to- day life. Our ancestors grew, hunted, harvested. It’s in our bones.

As difficult as my early life was, the land has always been good to me. I wouldn’t trade it for anything. What I went through at an early age gave me the grit to grow from a pigtailed little girl in dirty overalls to the founder of a company that’s sold more than a billion dollars’ worth of fresh produce.

I marvel at how much has happened to me right here on this one piece of land. It was here that my restless spirit was born and that I conjured dreams of far-off places. I spent the majority of my early years planning my escape. And yet when I had the opportunity to leave, I didn’t take it. As my company grew, I began to travel on business constantly. I’ve been to some of the most amazing places. I’ve worked with some of our country’s most powerful people. And yet my soul is rooted here on the same piece of earth where I grew up. I hate it and I love it, and I suspect that I would wither like a harvested plant if I ever left.

Well-meaning advisors have told me that I should hide certain parts of who I am — either to conceal my humble origins or to minimize my current success. When I started my business at age sixteen, most days I wore jeans, work boots, and a baseball cap. People said, “How can she be a businesswoman dressed like that?” Now when I wear heels and a skirt, people say, “How can she be a farmer?”

I’m sharing things in this book that for a long time I never dreamed of sharing with anyone, much less the world. Confronting colleagues with the more complicated truth would have taken time and energy. It was easier for me to let people believe whatever they wanted or needed to believe in order to accept me as someone who belonged at the negotiating table or the cocktail parties.

Over time, though, I’ve become brave enough to be myself no matter where I’m at and who’s in the room. I have a newfound appreciation of where I come from, what I’ve experienced, and where I am now. My community is filled with those I care deeply for. We don’t hear enough from people who come from the humble small towns of America, from people who know what it is to work with their hands from morning until nightfall, and who find ways to thrive without abandoning their roots.

Looking back on last night’s gathering, I know I belonged there as much as anyone did. In fact, my hardscrabble background gives me the advantage of perspective. I’ve done just about every working-class job you can think of. I’ve been the truck driver. I’ve been the cashier. I’ve been the field hand. Today I’m the boss. My story is the story of America, rich and destitute, raw and polished, damned and blessed. And it starts in a poor, tiny village in the middle of the country.