It took 20 years of having ADHD to realize that it wasn’t ADHD at all, I was just extremely hyperactive. After coming to that conclusion, I discovered a way to focus that required zero drugs or other external therapies.

DISCLAIMER: This is what worked for me and not medical advice

It’s worth saying that there are definitely serious medical and mental issues that should be addressed with therapies and medications, it just wasn’t the best remedy for my brain. I believe we live in an overly medicated society and one where it’s too convenient to create excuses―and my instinct is that it’s a bad thing. I’m not a doctor and my thoughts and experiences are anecdotal, but I think they will resonate with the collective thinking on ADHD.

My (legally) medicated journey with ADHD

I was diagnosed with ADHD in the 1990s when I was around 10 years old. Some combination of hyperactivity, boredom in a traditional school setting, and tragedy in my childhood meant I was on a drug cocktail for years afterward. Hyperactivity meant I had a lot of energy. Depression and a healthy dose of opposition to authority made me unmotivated to do the things I was told. Ritalin, Adderall, Wellbutrin, Prozac…both separately and combined. We used drugs to balance out my mood for years. It was hard to have these mood changes and not know which part of it was the real me–especially during my formative years when I didn’t yet know myself.

Whether I had ADHD or not is debatable. A doctor diagnosed it after a series of tests. Looking back, whether the diagnosis was accurate or not is still ambiguous. When I was growing up, I was able to focus on things I loved or that were fun. Math, sciences, art, music were all subjects that garnered my intense focus. A specific example is that I practiced guitar five hours per day for years as a teenager. If I truly had ADHD, how could that have been possible? Or, is that the very definition of ADHD?

I refused medication as much as possible in college except in last-minute sprints when I really needed to focus — an imminent due date for a paper or exam. This is a common pattern I’ve seen in other students. Access to legal methamphetamines plus a better-than-average short-term memory meant I was still able to pull off good grades — despite my procrastination. That and the convenience of my diagnosis enabled me to maintain this pattern for years with few negative consequences, though it’s hard to imagine where my life would have gone had I shifted patterns sooner.

Turn Off, Tune In, and Live Passionately

Everything changed when I was 21 years old and forced to confront the real world. Out here there aren’t tests and grades to validate success. You make your own game and you succeed or fail at achieving your goals. I wanted to produce my first album. I was already a multi-instrumentalist and understood composition, but there was a lot to learn and I had no idea how to delegate back then. I had to learn how to record to get the best sound, how to create beats, how to mix music — basically to be both the instrumentalist and the audio engineer. I was writing and recording all day on top of reading textbooks on audio engineering. It was an impossible amount of work. I worked from 6 am until midnight or later every day (and have ever since). The sheer volume of work meant I had to force myself to focus if I was going to succeed.

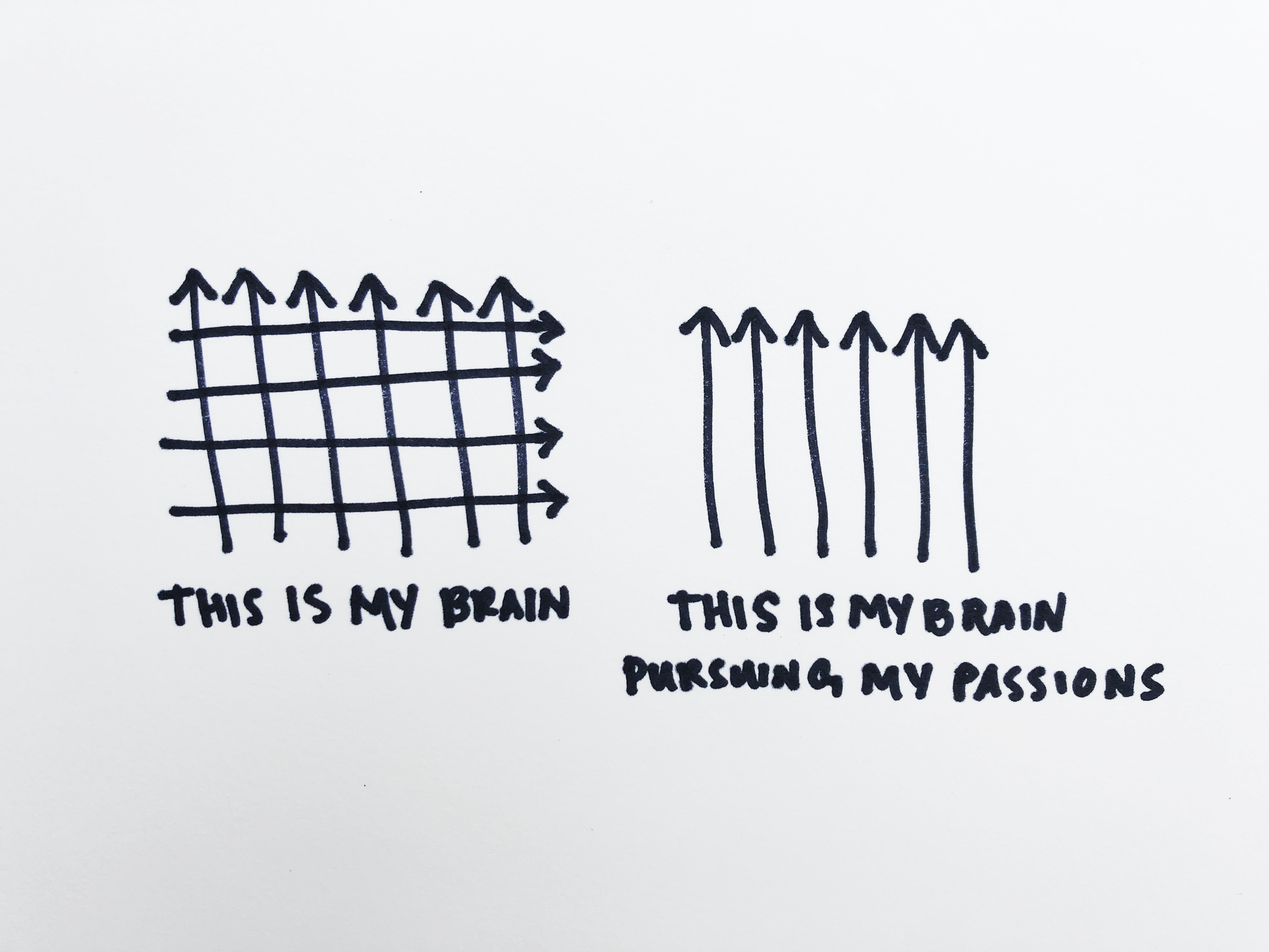

Over the next six months, I came to realize that I could repurpose my ADHD as a strength. I just had to intensely focus on my own challenges and passions. Years later, I no longer produce music, but I have another calling: entrepreneurship. It is extremely challenging. On top of building companies, I set difficult challenges for myself every quarter. Learning new languages, quotas on books per month, learning new instruments or challenging pieces. My ADHD was a weakness that has turned into a strength — an incredible amount of energy that can go into my passions.

I’m not an advocate for multi-tasking, nor does that work for me. Instead, I intensely focus on whatever tasks I have at hand until they are complete. The reason this works for me is that I need a lot going on to stay engaged. Easy games aren’t fun for me. I love the challenge of having a lot on my plate and the pressure of figuring out how to prioritize and accomplish it all within a specific timeline — otherwise I get bored and start making careless mistakes.

Distracted new world

I can only imagine it is even harder for kids growing up today to focus in school, even prior to the pandemic. They have all the same challenges I had, plus the tricks social media plays on your mind. We live in a more distracted world than ever before. There is so much information out there that it’s hard to understand what is true, false, or even worthy of our attention.

It’s a convenient solution to take a child who doesn’t learn in the same way as others, label them with a problem, and prescribe medication. This is much more convenient than revolutionizing the education system — or coming up with an individualized plan for your child that doesn’t rely on what’s readily available. Looking back on my own history with ADHD, I’m left with a new question:

Is it possible that school is boring and teaches kids a lot of irrelevant material they’ll never need — and that some of the smartest kids are the ones who realize their time could better be spent learning or building something else?