“Nursing is a heavy responsibility. Before, it felt like a privilege to be in charge and have autonomy as a nurse, but with COVID the responsibility is critical.”

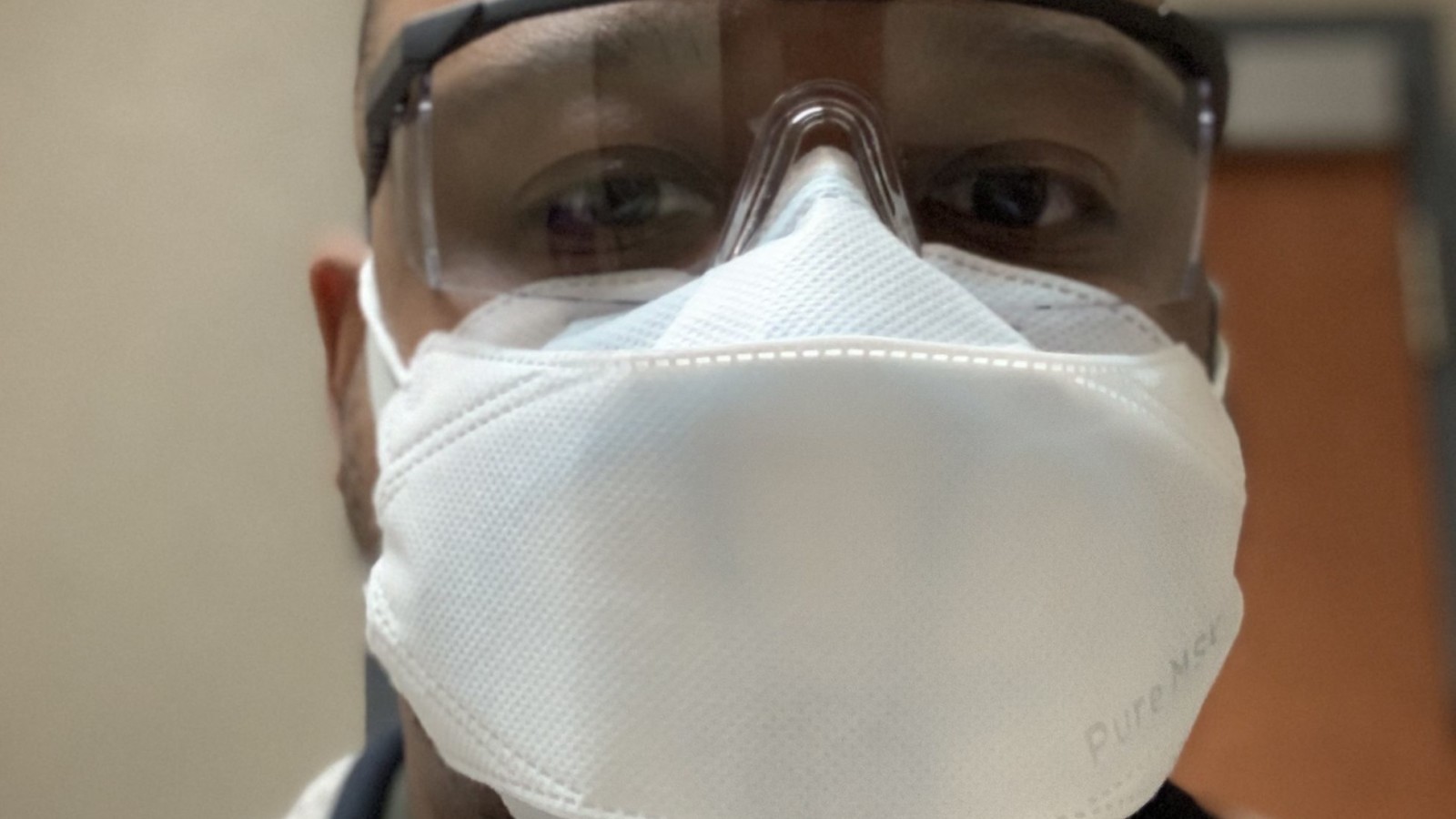

Melvin Foy, RN MSN (Atlanta, GA)

Melvin Foy was thrilled when he received the news that his wife was pregnant in March 2020. It was their second child. Melvin was months away from finishing nursing school. Though the pandemic was swelling, he was optimistic things would be back to normal by the time his little one was expected in December. “We were excited and grateful – I didn’t see the impending threat of COVID-19. [The baby] was welcome news, and we assumed the pandemic would be over by then.”

Just two years earlier, Melvin decided to leave his career in sports medicine as an orthopedic trauma specialist and expand his love for medicine by applying to nursing school. He was selected for an intense accelerated program at Emory University. In this program, he would earn his nursing degree and certification as a Nurse Practitioner simultaneously. He was excelling and was navigating his clinical practicals when the pandemic hit. “Me just coming in, I had to learn on the fly.” He was side by side with seasoned nurses who were dealing with the complexities of COVID patients. Watching the experienced practitioners navigate the challenges of COVID-19 was quietly reassuring to Melvin. “It was almost as if we were all new again.” While he was learning about COVID, he was also learning about obstetrics and gynecology. “OBGYN is something I studied heavily in school as I was unfamiliar with it from sports medicine.” He kept a close eye on his wife. “I was aware of all the dangers presented and kept them in the back of my mind.” Melvin’s wife suffered from hypertension in her first pregnancy, but with her second pregnancy she was asymptomatic and not presenting any illness. Melvin’s expanding knowledge was a comfort. “I was able to keep her worry at bay and stay realistic through the first trimester.”

Implementing preventative measures to stop the spread of COVID became an additional complication for the couple. “This pregnancy was very different because around the time my wife started weekly doctor visits, I wasn’t allowed at any of the appointments.” Between hospital restrictions and Melvin’s need to stay home with their other daughter, there was a disconnect. “[This pregnancy] wasn’t the same at all. My wife wasn’t showing as much as in her initial pregnancy. I didn’t hear the baby’s heartbeat until my wife was hospitalized.”

Six months into the pregnancy, Melvin’s wife was diagnosed with preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Doctors decided the safest place for Melvin’s wife and daughter to gestate would be in the hospital. Melvin had just received notification that he could resume his nursing school clinicals, which had been on hold due to the pandemic and were critical to completing his degree. “It was a lot rushing from one hospital to another. It was the final semester of Nurse Practitioner school. We were all behind on [clinical] hours. I had a lot of making up to do.”

Melvin’s wife’s condition worsened. The physician decided at 27 weeks to deliver the baby via cesarean. Unfortunately, his wife’s epidural didn’t take, and she had to be put under general anesthesia. That meant Melvin couldn’t stay with them for the delivery. “I was in the post-procedural room … waiting. It was quite terrifying. It was just me, and I wasn’t sure how things would turn out.” It was his wife’s first C-section, and at 27 weeks there were significant concerns about his daughter’s health. “I just prayed her lungs would be mature enough.” The baby was delivered and able to let out a cry before she had to be intubated. It was a good sign. She weighed just over a pound at birth, barely the size of Melvin’s palm. Because of COVID, Melvin’s time with his little girl was limited. “I was allowed to visit once a day for four hours.” The nurses in the NICU did as much as they could to keep Melvin’s family connected. “They worked really hard to keep us informed. A few times our daughter got sick, and we had already visited for the day. They were very kind to break protocol and allow us to come again.”

Melvin’s experience with the nurses in the NICU deeply affected the way he treated his own patients. “Half of the COVID patients I see are technically ICU patients. Under normal conditions they would be in transition or step down for ICU.” Melvin says treating patients with coronavirus takes a different level of physical and mental preparation. He regularly treated multiple patients who were put on vents and drips and needed direct care. He also had his regular ER patients to care for with their inevitable unknowns. The pandemic heightened Melvin’s awareness of the gravity of nursing. “Nursing is a heavy responsibility. Before, it felt like a privilege to be in charge and have autonomy as a nurse, but with COVID the responsibility is critical.”

Melvin recalls an elderly patient who came in suffering from respiratory problems. Her PCR test came back positive, and she was frantic. Melvin pulled from his experience with the newborn nurses and proceeded delicately. “I took time with her and her family. I talked them through what was happening currently and avoided the worst-case scenario.” The patient had heard the terrible prognosis on the news. She was fearful because of her age and preexisting conditions that she would become a statistic. “She reminded me of my grandmother. I related to her and she trusted me.” He consoled her and walked her family through the treatments and expectations step by step. Melvin says fear can be debilitating, and removing fears has been critical to patient recovery during the pandemic. “What makes nurses great is we’re always asking, ‘What’s best for my patient?’” Melvin took comfort that the same passion for care was being provided for his family.

Melvin and his wife were able to bring their daughter home from the hospital after three months in the NICU. It was New Year’s Day. She was still on oxygen but was bottle feeding, which was a huge accomplishment for their tiny baby. “She still has a long road to travel, but just to see that she and my family are OK is enough for me.” Melvin leans on knowledge and faith to help him cope with the pressures. “Worrying about caring for yourself diminishes your ability to care for others. God put me here in this place, so he’ll take care of everything that needs to be taken care of. I know he will never give me more than I can bear.” Melvin says perspective is paramount: “Even if this is difficult for me today, this may be this patient’s worst day. So I hope to help bring some joy or peace to them. I just keep the perspective that I’m doing the best that I can.”

#FirstRespondersFirst Microstep

When you’re washing your hands, take the 20 seconds to think of three things you are grateful for.

This will help you lower your risk of viral infection while reinforcing a more positive mindset.

Melvin’s story is part of “Unmasked: Profiles of Humanity and Resiliency,” a collection of stories from the frontlines published by the National Black Nurses Association (NBNA) in partnership with #FirstRespondersFirst. The NBNA offers therapy and wellness services through RE:SET, a free mental wellness program developed for Black nurses to help them RE:SET, recharge and widen their circle of support. Visit nbnareset.com to learn more.