About 10 years ago, Dee Williams was living in a 1,500-square-foot, three-bedroom house in Portland, Oregon. She had a $1,200-per-month mortgage, which she split with housemates to help make ends meet. The 1927 Craftsman-style bungalow had no insulation and was “miserably cold in the winters,” says Williams, now 51. “We paid $600 a month in utilities, because we barely inched the heat up just enough so we didn’t chip our teeth chattering.”

All her time was spent either working on the house or working to pay for the house and its upkeep. Then one day while in the grocery store, Williams collapsed. After being diagnosed with congestive heart failure, she began reevaluating her life and the place she called home.

Williams wanted to be an environmentalist. She wanted to volunteer and help her friends more, and overall just be a better person. For that she needed two things: time and money. She quickly realized the major drains on these two things were her house and mortgage payments. So she sold her house and set out to build a tiny house that would give her the life she wanted.

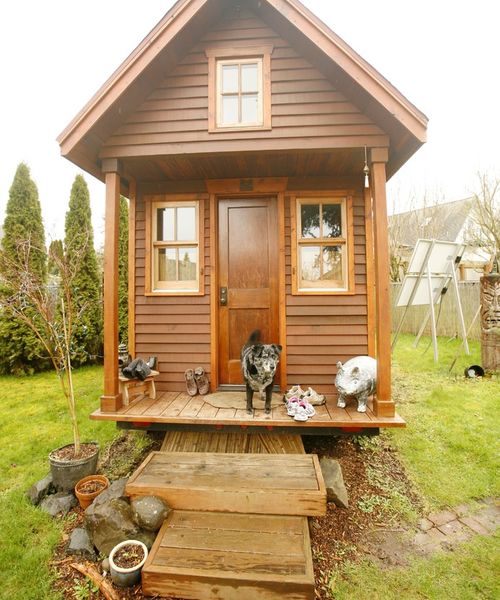

Williams has lived in her 84-square-foot house in Olympia, Washington, for a decade now, and has just released a memoir called The Big Tiny: A Built-It-Myself Memoir, which chronicles her serious downsizing and lifestyle changes. “I wanted to explore what it has really offered me, what I am like now compared to 10 years ago when I built my little house,” she says.

After her diagnosis, selling the house was a way to regain control of her cash so she wasn’t swimming in debt. “The diagnosis for congestive heart failure is pretty crappy,” she says. “I’m not going to live 30 years, so why would I have a 30-year-mortgage for a house I’d never own?”

Two other events solidified her decision for a lifestyle change around the same time: a trip to Guatemala, where she saw extreme poverty, and her good friend’s succumbing to cancer. “I began to question everything about the world around us and what it is about the environment and stress that causes us to get sick,” she says. “I thought if I could be the generous, kind person I imagined I could be, how would I do that? How could I give money when I wanted? How could I volunteer to paint the backdrop for the high school play if I wanted?”

That’s when it clicked that without a mortgage, and with minimal utility bills, she could work less and live life more. And she channeled this simplistic vision into the design of her new tiny home. “I had this picture of a triangle plopped down on a square, like a house that kids draw,” she says. “Somehow, if I could create this sense of home that was that simple, all the things that were so confusing for me, like heart failure and living in the shadow of possibly dying, would become clear.”

Williams now works 24 hours a week as a hazardous waste specialist for the Department of Ecology. The rest of her time is spent volunteering, taking care of neighbors, babysitting for friends and teaching tiny-house-building workshops through Portland Alternative Dwelling, which she founded. “I also have an impressive résumé in goofing off,” she says.

Williams’ new lifestyle has connected her to her immediate community. “If my neighbor is moving, I have time to help,” she says. “If an organization needs volunteers to help pull invasive ivy, I can do that.” Because she doesn’t have a refrigerator, only a cooler, she shops for fresh produce every day at the local grocer. She frequents the library and Laundromat, local pubs and coffeehouses. “These are extensions of the community,” she says.

Time has become her most valued and abundant possession. “I have time to notice my natural environment and take a breath through the seasons, to puzzle over the way that nature is throwing itself at me and the community. I live in one of the most beautiful places on the planet. If you’re working all the time, sitting inside, you miss a lot of it. I feel lucky and blessed that I’ve been able to pay attention to it.”

Related: Discover Innovative Home Interiors Big to Small

As you step inside the home, a kitchenette with a one-burner stove and a sink are to the left. Williams brings in a 2-gallon jug of water for doing dishes, making tea and brushing her teeth. A jar below the sink collects greywater, which she uses in the garden.

A bathroom is on the other side, with only a toilet. She showers at work or at as neighbor’s house. She used to have a composting toilet before the city made her bag her waste instead. A closet holds her limited wardrobe, “both pairs of shoes,” she says, and a solar array battery. The 6-foot by 7-foot “great room,” as she calls it, has an 11-foot ceiling with a skylight. A ladder nearby allows her to climb to the sleeping loft.

Related: Find Futon Covers for the Ultimate Space-Saving Furniture

It took Williams three months and $10,000 to build the home. About $2,200 of that went to the solar system. She doesn’t pay rent, mortgage or property taxes. Her cell phone is her biggest monthly billed expense, but her company pays for that. Utilities for her propane gas heater and cook stove run her about $8 per month in the winter.

As far as material possessions go, Williams says she has had to come to terms with what she wants and what she needs. “I couldn’t have come to that understanding if I wasn’t on a diet of space,” she says. “I have nowhere to put anything, so I really have to examine everything I buy to determine where it’s going to go; am I going to use it? Can I borrow it instead? A whole new relationship to stuff has been forced on me.”

This is a list of Williams’ possessions. “The only thing missing is the house,” she says. “I encourage everybody to make a list, even if it’s just your junk drawer. It’s like playing anthropologist with yourself.”

Another suggestion of hers is to set a schedule for paring down your possessions. Her sister-in-law, for example, donated a grocery bag full of things like clothes and toys every day during Lent — 40 days, 40 grocery bags. “Practice going through stuff and try letting it go and getting it back into circulation for people who need it,” Williams says. Most of her friends and family know now that if they give her something like a coffee mug for Christmas, it’s likely to get regifted.

“I’m happy only 85 percent of the time, roughly three hundred days out of the year,” Williams writes in her memoir. “The other days, I wish I had running water or that the house was warmer … or a seventy-inch plasma screen television and enough space to invite all my friends over to watch the Oscars … a flushing toilet and an endless supply of cheap beer. … I might want a lot of things … but that doesn’t mean I need them.”

Original article written by Mitchell Parker on Houzz