As world leaders continue to marshal medical “troops” in the ongoing “war” on Covid-19, we can turn to one of the modern world’s greatest first responders — the “mother of modern physics” — for hope and inspiration. When Madame Curie combined her scientific genius and moral conscience to tackle the life-and-death conditions of thousands of soldiers on battlefields during the First World War, she provided a blueprint for the future: masterminding new life-saving medical strategies, creating novel networking systems, and cultivating psychological resilience in the midst of unforeseen death and trauma.

In 1914, the world was thrown into sudden unimaginable upheaval. World War I erupted as Europe’s great powers battled for supremacy on the continent and around the world. Germany and Austria-Hungary pitted themselves against France, Great Britain and Russia. Military forces were massively organized. Other nations joined in the titanic political and military struggle.

This was mass warfare.

“Total war” had its antecedents in the 19th century, but the new battlefield carnage was on a scale never before seen in world history. In the first truly mechanized war, modern manufacturers mass-produced machine guns and explosives with unprecedented accuracy, speed, and lethality.

On battlefield after battlefield, hundreds of thousands of soldiers fought and were often left to die after sustaining wounds. As the new bullets and bombs flew, casualties of both soldiers and civilians climbed to the millions.

This unprecedented scale of suffering required a new vision for first responder medical emergency care: new types of medical personnel, rapid-fire communications, efficient transportation of patients, coordinated networking among experts to ensure proper protocols, new kinds of medical supplies, and available space (often improvised) to house patients during their recovery.

Something had to be done.

A petite introverted woman stepped forward to fill the void in the treatment of the war’s wounded and critically ill soldiers. She had already made world history by discovering radioactivity. She had already been recognized as one of the world’s greatest scientists. She had already been the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, and received a second eight years later. She had already taught as the first woman professor at the Sorbonne in Paris. She had already discovered two new elements. And she had already shaped the foundations of the emerging field of nuclear physics.

She was Marie Curie, dubbed the “mother of modern physics” and “the greatest woman in the world” at the war’s end by news media during a trip to America.

Madame Curie had few pretensions. She was painfully socially awkward. She wore a sling on her arm to feign an injury in order to avoid shaking hands with adoring fans or standing in reception lines with dignitaries. She was bored by fame. She canceled appearances at galas held in her honor. She had no interest in photo ops, public appearances, speechmaking, fancy clothes, or what might be the equivalent today of “likes” in the current social media world. She wanted to do her job quietly as a scientist or help to heal a war-torn world.

As World War I intensified, Curie determined to use the science she knew best to provide new cures. She moved expertly among political leaders and medical experts to do that. She built social networks among health advisers and medical engineers across nations to shape new international health policies and protocols. She became the first director of the Red Cross’ radiological services and designed x-ray technology that could be adapted to mobile ambulance vehicles to bring healing to the battlefield. She reasoned that x-ray use could save human lives and limbs, and worked to make that happen. Her vision was to bring x-ray imaging directly to surgeons on the battlefield to pinpoint where bullets and shrapnel had penetrated the body and where bones had been broken. With this knowledge, surgery would be precise, swift, and less prone to infection.

Now she donned a simple white gown and took driving lessons to learn to steer the new medical emergency units she had helped to design. The wounded soldiers who were x-rayed in these vans nicknamed them “petite Curies” — “little Curies” — in honor of their inventor. Curie’s vans carried the first medical x-ray machines in the world to image battlefield wounds. By the war’s end, over ten thousand soldiers had been treated in “petite Curies.”

The woman who coordinated the military engineers, doctors, and technology experts to do this also trained 150 women nurses to perform the x-ray imaging in them. By today’s standards, exposure levels were high for both medical staff and patients, but sophisticated metrics and protection had not yet developed. Bullets and shrapnel were successfully extracted, and broken bones realigned. Along with the twenty mobile x-ray unites, Curie helped establish 200 permanent radiology centers for battlefield casualties.

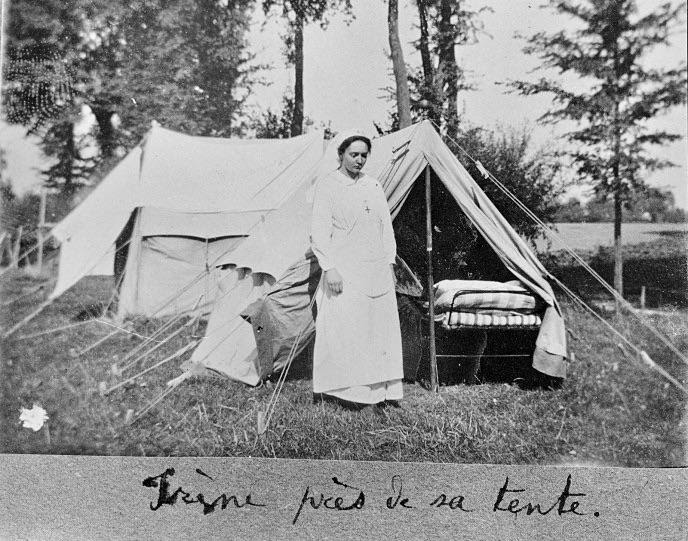

Curie’s seventeen-year old daughter Irene, who would herself become a Nobel-winning physicist, accompanied her mother across rutted roads to treat patients after she received emergency medical training as an x-ray nurse and technician. At times she shared a battlefield tent with Curie or a sparse room at hospitals they visited to set up x-ray machines.

Curie lobbied governments to allow her to set up these x-ray imaging centers. She united public and private sectors to work for the common good. She persuaded the wealthy to donate cars. She requested private companies to donate equipment, and engineers and mechanics to adapt vehicles for x-ray use. As the mother-daughter team drove up and down the trench lines of France and Belgium, they kept track of their van’s journey on a map they posted on their wall. In the midst of agony and death, with limited food supplies and dangerous conditions all around, Curie and Irene showed remarkable grit, skill and empathy for their patients.

Curie noted later, “The use of x-rays machines saved the lives of many wounded men. It also saved many from long suffering and lasting infirmary.” An estimated one million men received x-ray treatment before the war’s end.

Madame Curie’s perspective on life and this work was humble. “You cannot hope to build a better world without improving the individuals,” she said. “To that end, each of us must work for our own improvement and, at that same time, share a general responsibility for all humanity.”

She added: “Life is not easy for any of us. But what of that? We must have perseverance and above all confidence in ourselves. We must believe we are gifted for something, and that this thing, at whatever cost, must be attained.” At one of the lowest points in the war she wrote to Irene, “We need great courage, and I hope we shall not lack it. We must keep our certainty that after the bad days the good days will come again.”

Einstein would write, “Marie Curie is, of all celebrated beings, the only one whom fame has not corrupted.”

From the start of World War I to its conclusion in 1918, Curie created a radical new vision for first responders to combat an unforeseen world-spanning catastrophe. As our own first responders risk their lives in the “war” against Coronavirus, we can honor Curie’s leadership and that of other predecessors who also risked everything to heal the trauma of the world. Madame Curie spoke presciently to future generations when she enjoined us to remember that “good days will come again.”