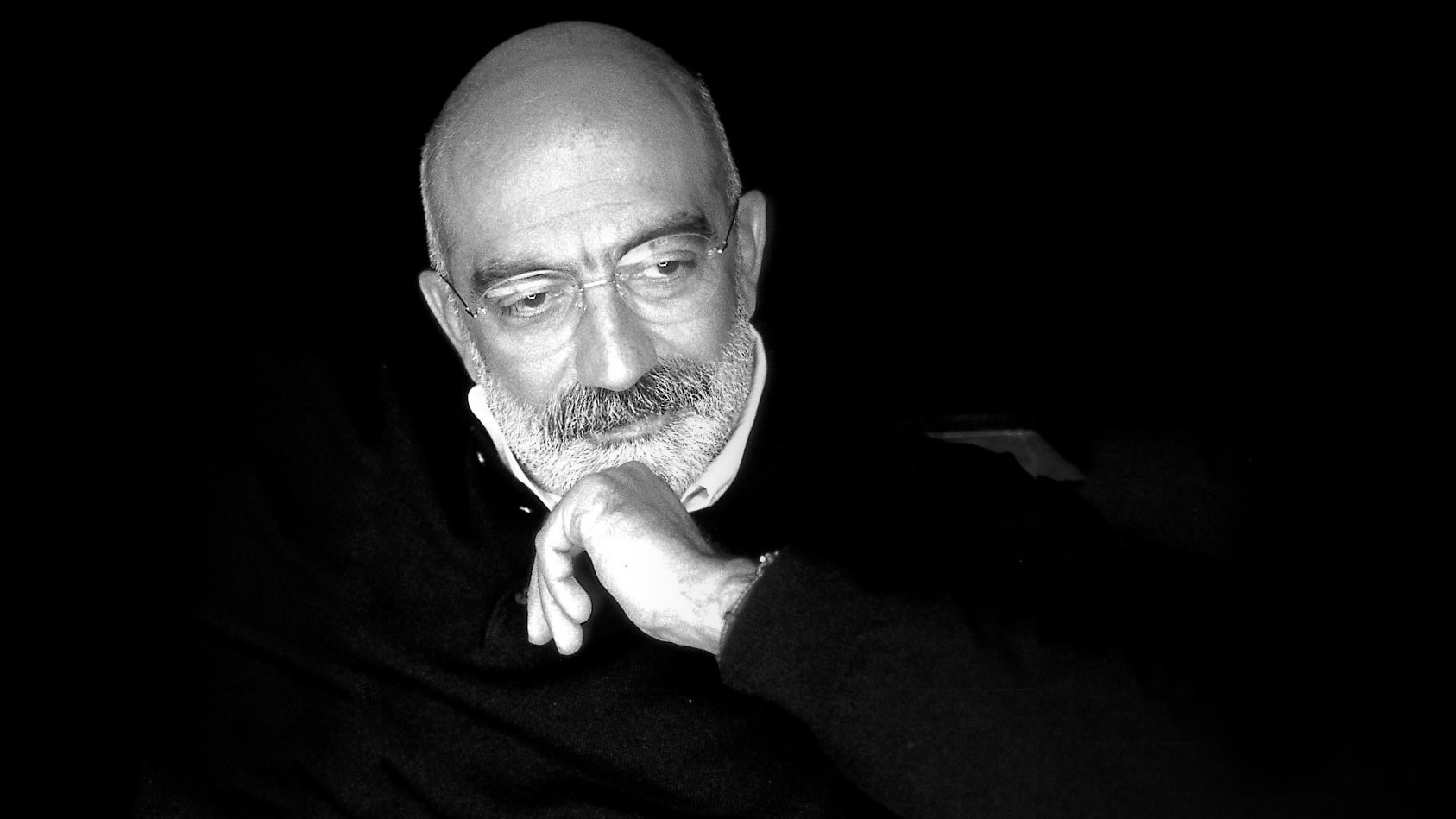

A moving object is neither where it is nor where it is not, concludes Zeno in his famous paradox. Ever since my youth I have believed this paradox better suited to literature or, indeed, to writers than to physics.

I write these words from a prison cell.

Add the sentence “I write these words from a prison cell” to any narrative and you will add tension and vitality, a frightening voice that reaches out from a dark and mysterious world, the brave stance of the plucky underdog and an ill-concealed call for mercy.

It is a dangerous sentence that can be used to exploit people’s feelings, and writers do not always refrain from using such sentences in a manner that serves their interests when the possibility of touching a person’s feelings is at stake. Even understanding that this is their intention may be enough for the reader to feel compassion toward the writer of that sentence.

Wait. Before you start playing the drums of mercy for me, listen to what I tell you.

Yes, I am being held in a high-security prison in the middle of a wilderness. Yes, I am in a cell where the door is opened and closed with the rattle and clatter of iron.

Yes, they give me my meals through a hatch in the middle of that door.

Yes, even the top of the small stone-paved courtyard where I pace up and down is covered with a steel cage.

Yes, I am not allowed to see anyone other than my lawyers and my children.

Yes, I am forbidden from sending even a two-line letter to my loved ones.

Yes, whenever I must go to the hospital they pull handcuffs from a cluster of iron and put them around my wrists.

Yes, each time they take me out of my cell, orders such as “Raise your arms, take off your shoes” slap me in the face.

All of this is true, but it is not the whole truth.

On summer mornings, when the first rays of the sun come through the naked window bars and pierce my pillow like shining spears, I hear the playful songs of the birds of passage that have nested under the courtyard eaves, and the strange crackles prisoners pacing other courtyards make as they crush empty water bottles under their feet.

I wake up with the feeling that I still reside in that pavilion with a garden where I spent my childhood or, for whatever reason (and I really don’t know the reason for this), at one of those hotels on the cheery French streets of the film Irma la Douce.

When I wake up with the autumn rain hitting the window bars, bearing the fury of northern winds, I start the day on the shores of the Danube River in a hotel with burning torches out front, which are lit every night. When I wake up with the whisper of the snow piling up inside the window bars in winter, I start the day in that dacha with a front window where Doctor Zhivago took refuge.

I have never woken up in prison – not once. At night, my adventures are filled with even greater activity. I wander the islands of Thailand, the hotels of London, the streets of Amsterdam, the secret labyrinths of Paris, the seaside restaurants of Istanbul, the small i will never see the world again 210 parks hidden in between the avenues of New York, the fjords of Norway, the small towns of Alaska with their roads snowed under.

You can run into me along the rivers of the Amazon, on the shores of Mexico, on the savannahs of Africa. I talk all day with people who are seen and heard by no one, people who don’t exist and won’t exist until the day I first mention them. I listen as they converse among themselves. I live their loves, their adventures, their hopes, worries and joys. I sometimes chuckle as I pace the courtyard, because I overhear their entertaining conversations. As I don’t want to put them on paper in prison, I inscribe all of this into the crannies of my mind with the dark ink of memory.

I know that I am a schizophrenic as long as these people remain in my head. I also know that I am a writer when these people find themselves in sentences on the pages of my books. I take pleasure in swinging back and forth between schizophrenia and authorship. I soar like smoke and leave the prison with those people who exist in my mind. Others may have the power to imprison me, but no one has the power to keep me in prison.

I am a writer. I am neither where I am nor where I am not.

Wherever you lock me up I will travel the world with the wings of my infinite mind. Besides, I have friends all around the world who help me travel, most of whom I have never met.

Each eye that reads what I have written, each voice that repeats my name holds my hand like a little cloud and flies me over the lowlands, the springs, the forests, the seas, the towns and their streets. They host me quietly in their houses, in their halls, in their rooms.

I travel the whole world in a prison cell.

As you may well have guessed, I possess a godly arrogance – one that is not often acknowledged, but that is unique to writers and has been handed down from one generation to the next for thousands of years. I possess a confidence that grows like a pearl within the hard shells of literature. I possess an immunity; I am protected by the steel armor of my books.

I am writing this in a prison cell.

But I am not in prison.

I am a writer.

I am neither where I am nor where I am not.

You can imprison me but you cannot keep me here.

Because, like all writers, I have magic. I can pass through your walls with ease.

Excerpted from I Will Never See the World Again by Ahmet Altan with permission from the author and publisher.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.