Witnessing another’s loss can be uncomfortable. Here’s what you can do — and what to avoid.

Last year was a difficult one for me. My parents had both been sick for years. My father hadn’t been himself for over a decade, and my mother began showing signs of Alzheimer’s disease five years earlier. That brought a long but urgent process of tending to them, making healthcare decisions, and trying to be patient amid my own frustrations. As they both grew more ill with each passing month, I thought I had said goodbye. When they died less than 100 days apart in January and April of last year, a grief unfolded that was messier, slower, and lonelier than I expected. Although no one can alter the reality of another’s loss, my experience illuminated ways in which others’ actions could act as a salve. Here’s some advice for helping someone in your life who is grieving.

- Avoid reciting overused phrases. Offering up “So sorry for your loss,” for example, or “You’re in my thoughts and prayers” is well-meaning at a sensitive time, but it doesn’t do much to help. Even a little personalization can be comforting. For example, a friend told me, “I’m feeling your loss,” and that somehow felt so much better, like he was really trying to empathize with my situation. For a little while at least, I wasn’t so alone.

- Resist the urge to point out the positive. Although death does often represent an end to illness and the struggles that come with it, the grieving suffer a considerable loss. I found it painful when someone would suggest that I should be relieved or even happy when my parents died. Although I could rationally acknowledge the upside to their deaths, my raw emotion was sadness. I struggled when my mother’s friend responded that her death was “good news.” It was not good news. I had just lost my own mom, my children lost their grandmother, and that still feels terribly sad. There’s no reason to put a happy face on another’s loss.

- Don’t be afraid to reach out. Grief can make us uncomfortable, just like death can make us uncomfortable. I have been surprised how lonely I can feel in my grieving. Although I am not the only one to grieve my parents, others do it from their own vantage points. I was the only one who knew them the way I knew them, who needed them the way I needed them. Hence, a feeling of loneliness often creeps in, even now. That’s why I benefit from friends who seek closeness. Sympathy cards, however quaint, were welcome in the early weeks. Here’s my advice: go ahead and send a grieving person that friendly checking-in text. Suggest a meetup for lunch. Invite him or her to join you on an outing — all the same things you would normally do. That person may need companionship now more than ever.

- Realize that the grief journey isn’t predictable. An individual may not be at his or her worst right when a loved one dies, then gradually feel more and more normal with each passing day. On the contrary, in the initial aftermath of a death, a survivor may look and act relatively normal. Informing old friends and associates of the death, tending to legal and financial matters, and addressing funeral plans can all be early distractions. It’s the moving forward that may pose hidden challenges. The month of October, as the six-month anniversary of my mom’s death passed, was difficult for me with tears nearly every day. Be aware, therefore, that the person in your life may be having a harder time one week than the prior one, and that the passing of time doesn’t necessarily advance healing.

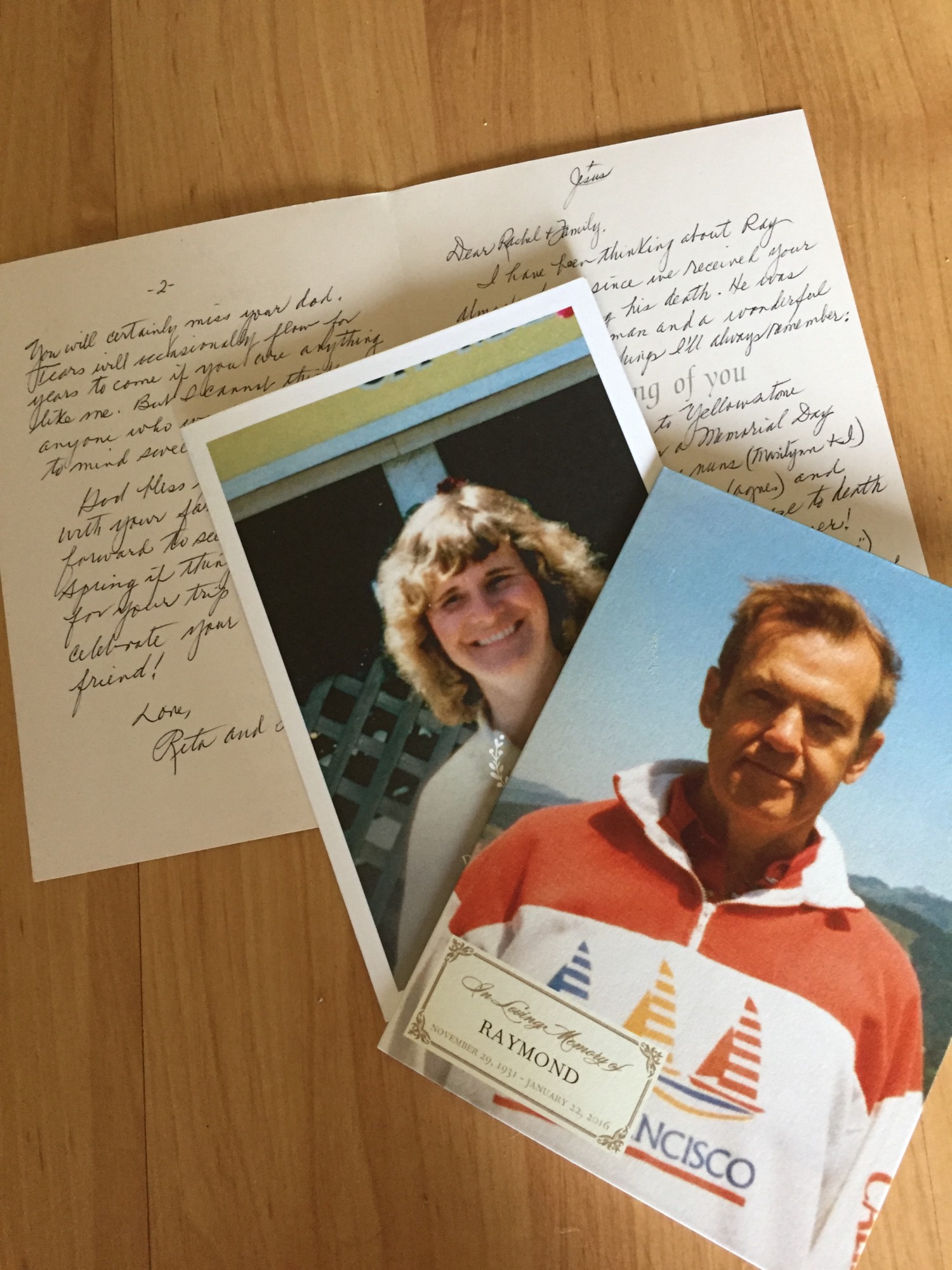

- Share what you know. One poignant aspect of the grief experience is the realization that there are no new memories to make. My father will never share any more wisdom with me; my mother and I will never commiserate over anything again. Therefore, I’ve enjoyed when people volunteer memories they have of my parents. Their longtime friend wrote a letter describing a particularly cold camping trip with my dad, for example. Photos of the deceased, letters they wrote, memories of times together — even those that seem pretty ordinary — suddenly become cherished “new” pieces that can be a tremendous gift for a grieving person.

- Understand that it’s okay that you haven’t suffered the same loss. I was orphaned at age 41. Most of the people in my circle of friends haven’t lost a parent; a handful still have grandparents. I know this. Still, it’s not necessary for my friends to avoid talking about their own parents. I might get a little choked up when observing healthy older parents traveling, babysitting and enjoying life, but I’m happy that they’re there. Really. Part of my journey through grief has been the acceptance that the pain I feel is one of the costs of love. Those who still enjoy parents, or a spouse, or a child, and will for years, bring more joy to the world. Share that joy — there’s plenty to go around.

Originally published at medium.com