Some of you may not remember what screen time meant for young children in the simpler era of yesteryear. First, that term screen time didn’t even exist because there weren’t different types of screens to distinguish; there was just one — that big box, sitting in the living room. Programming, meanwhile, consisted of Sesame Street, Mister Rogers, and, if you were lucky, the chance to watch Tom and Jerry attack and maim each other on Saturday mornings.

Ah, how things have changed. Movies and television shows became available to own first on videotapes, then DVDs, and now as downloads or streamed right to one’s television, phone, or tablet. Cable and then satellite companies helped increase the number of available channels from 3 to over 300. Video games emerged from a simple game of “pong” to visually spectacular and immersive worlds with missions you can play online against people across the world. And all of it now fits into the palm of our hands to access whenever and wherever we want it.

Eternal bliss, right? Not exactly. In my clinical practice, I can tell you confidently that conflict over screen time is easily the number one battleground between parents and children of all ages. And it’s no wonder that this is the case. Seeing a toddler zone out in front of an iPad on a beautiful sunny day or reenact the sword fight he just saw on Lego Star Wars against his little sister is going to cause at least some trepidation for most parents. Many people are quite worried, viewing screen time as nearly apocalyptic for the current generation. A recent article in The Atlantic by psychologist Jean Twenge was entitled, “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” And the answer was yes, using some data to conclude that smartphones are putting youth “on the brink of the worst mental health crisis in decades.” A widely viewed 60 Minutes segment in December 2018 also conveyed serious concerns about the ways that screens may be negatively altering brain development.

Yet others see media use as either no big deal or even a new digital reality that parents should be encouraging our kids to master as soon as possible. Do screens really make attentions spans worse, help some children read, or cause sweet toddlers to become irritable and aggressive? Does the amount of time or specific content of the media really matter? And what kinds of kids might be most susceptible to these effects? These questions and more will be addressed in this chapter on the behavioral and cognitive effects of early screen time. The overall hope is that if you are going to be forced to fight over this issue for the next 15 or so years, you might as well be armed with as much reliable information as possible.

A Few Practical Suggestions

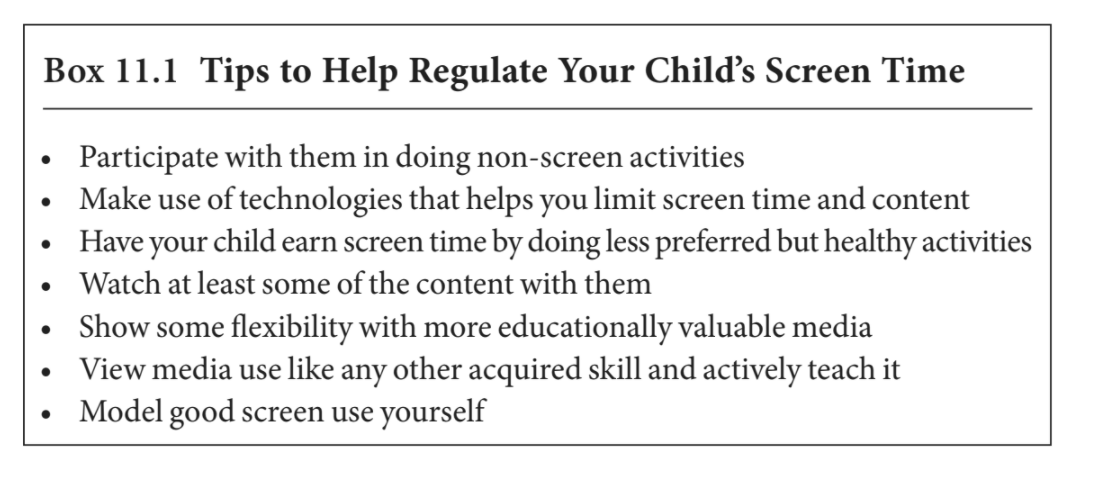

In recognition then that moderating a young child’s screen time is a worthwhile but challenging endeavor because it often runs against their temperamental tide, it is probably worth saying more than, “Good luck with that!” Remember, the good news here is that you are starting early with these limits so your child will be much more likely to accept them as part of life. There still may be a hump to get over initially with these new rules, but that’s much better than the mountain that is created by waiting until your child is a teenager. To get things started, here are some practical tips, as shown in Box 11.1.

“Go outside,” is probably not enough. To change behavior away from a reliance on screens, parental engagement is likely necessary. Keeping in mind that some kids really haven’t learned how to keep themselves busy without screens, parents may need to help come up with alternatives and then do some of those things with them, at least at first. Siblings can also help here, especially if “no screen” time is synchronized for everyone at the same time.

Fight fire with fire. By this I mean use a device’s own technology to help you set reasonable limits on screen time and content. There are also products that can be deployed at the level of a Wi-Fi router to manage multiple devices. They do cost money and can take a little while to learn, but this investment can be well worth it—especially when you get to have a machine telling your child their screen time is up rather than you (for the fourth time).

Earn it. The amazing pull of screens can be turned to an advantage when used as a motivator. If your child often resists playing outside, for example, maybe 30 minutes of active outside play earns her viewing of a 30-minute show. You can set the exact ratios in a way that works best. One caveat, however, is that this technique is probably best for activities that your child really does not have a natural interest in already. The reason is that the introduction of an external motivator like screens might take away some intrinsic motivation the child already has for the activity. If your child already likes to read, for example, having a child earn screen time by reading could make reading feel less inherently appealing. See chapter 8 on picky eating for more details about this phenomenon.

Watch with them. Especially when media content is the issue, it is important for parents to have a good idea of exactly what is being viewed. When watching shows or playing games together, there are opportunities to interact and discuss what is on the screen. Sharing the experience also helps parents learn about their child’s media preferences and tastes, so that you can make better conclusions about how media is or isn’t affecting your child. I know, I know—you may initially lose that golden time to get things done on your own, but don’t worry, your child will likely want to see the exact same thing 100 more times if you need to catch up on those emails.

Allow some extra flexibility for more educational content. Remembering that not all screen time is equal, one suggestion for kids who are begging for some extra tablet time is to say yes but insist that the programming be educationally valuable as a way to interest your child in shows like Sesame Street or more skill-building content. When our then 6-year-old began to rebel against some fairly stringent screen time limits, we downloaded an app that showed him how to play chess and told him time on this app, within reason, wouldn’t “count” toward his limits. While he’s likely not the next Bobby Fisher, he learned to play the game and still enjoys it.

Teach it. We don’t expect kids to just learn how to play baseball by themselves so why should we just leave kids alone to acquire media habits that will likely become a huge part of their modern life. Do some research on what shows to watch, what games and apps to use, and then show your child the ways that media use can enrich someone’s life without it taking over.

Don’t Be a Hypocrite. Even a 4-year-old can legitimately call you out for not practicing what you preach. Getting your child to look at an actual book is going to be much easier if she sees you looking at them, talking about them, and enjoying them too. Keep your own media use in check, especially when you are interacting with your child. The Facebook post will still be there, trust me.