Waking with the sun, on fresh, clean sheets. Windows and French doors wide open to the quiet country air. Birdsong from the branch of an ancient white oak, still healing from the great wildfire two summers ago. A glass of cold, fresh well water on the nightstand. There are no prescriptions in my medicine cabinet, not one. There are no handheld devices in the room, not one. Baby-bliss. The circadian life, no alarm set, primal well-being. Every day should be like this.

Oh, that’s right, it’s Saturday. First on my list, a menial and dirty task—which turned out to be anything but.

I, AI encountered my own ancient moonprint—I, AOL.

It started a couple of days ago, noticing 20 or 30 books stashed atop one of my studio bookcases. You know how it is, stuff you thought would make you smarter, spent good money on, didn’t use, didn’t miss, won’t waste, so never threw out. Brand new and obsolete. All these years, weirdly invisible yet not, just looked past it since around the turn of the millennium, judging from the titles. Using my light 6-foot aluminum stepladder, I climbed and carefully brought the books down. A fine powder of dust filled my nostrils.

And the thing that put me sideways, actually kind of upset me for a few minutes, is that the book titles were so backward I was embarrassed. Why had I hung onto these books? Who was that, and who is this? Did we all really see ourselves as so with-it, compulsive early adopters, so cool we sniffed with contempt at anybody who didn’t understand what bots are?

This simple housekeeping exercise became an eerie little voyage to the earlier me. Like Sherman and Mr. Peabody’s Wayback Machine—a little didactic ambush showing up in the middle of Rocky and Bullwinkle, just to keep things real.

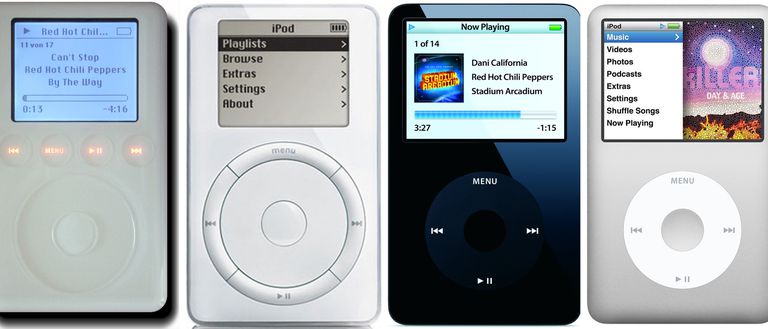

A relic from the day of Jeff Bezos’ original garage headquarters about “Electronic Commerce.” A book on how to make peace, or money—competing, not an issue—with AmericaOnline (that’s AOL to you), which was ironic because it was a book about how to succeed in the new platform which was very openly destined to kill bookstores. Learning to Use the World Wide Web, ©1998, a year when http://www. began appearing at the bottom of network TV ads. Streaming media? No such thing—only downloading low-resolution clips with Kbps buffering. iPods, iPhones and iPads hadn’t yet been invented. The only social media—another term not invented—was “chat rooms.” Aliases in those online conclaves were embryonic precursors of avatars for future platforms for uncontrolled impulses. And obscenity and violent threats were policed—long ago in that galaxy far, far away.

Until that little apocalypse on the aluminum ladder, I thought of my curated library walls, probably a couple of thousand books of all genres as touchstones to my fascinations. Not as a wall of dusty mirrors. Or a gallery of selfies, before selfies existed too.

How my self of twenty-four years ago, or even thirty minutes earlier, reacted atop the aluminum stepladder flew in the face of Alexa, Siri and every attempt at artificial immortality, is this:

We are everything we have ever been. And this is a wonderful thing. Because we aren’t robots. For we are not preprogrammed for anything—except progression.

Versioning.

Now, if you want to get technical about this, versioning—in the sense of becoming, evolving, change—is the natural order of life. However rococo or ridiculous our fortress of denial, our bodies will prove the premise.

They’re similes, but progression depends on our point of view about versioning. It doesn’t matter if we take up incremental embalming (as I think of medically and cosmetically unnecessary plastic surgery while we are still alive). It doesn’t matter if we believe, or don’t believe, in any specific theories whether science- or faith-based, or where we fit actual unearthed dinosaur fossils into all of this. We can get with the cloud (cyber, digital, AI, what have you), or cling to print like a life raft. We can take our groovy leather headband from Woodstock out for walks or we can eschew animal products entirely, wearing artificial leather and eating meatless meat. But versioning is assured. We change.

This conjures a whole new idea of “body clock.” Not the awareness of circadian rhythms, hunger pangs, or sleep cycles—but our body, as an actual, living clock. As a site called SkinAuthority explains, “[The] cycle of cell production and replacement slows as we age. It takes about 28 days for the average, middle-aged adult. As we grow older, this skin cycle slows to about 45-60 days in our 40’s and 50’s. It can further slow to about 60-90 days in our 50’s and 60’s.” For babies, this cycle is three to five days. Other cells, structures of our bodies, likewise in different ways or cycles. Continually versioning.

So one might say we’re both developers and new releases, but not of artificial intelligence. Life engineered, innovated. Early adopting, lucky setbacks. Incompatibility issues, testing, tested, upgrading, replacing—but always versioning. Bugs fixed, performance improvements.

Yes, of course I know that even for me, as for dinosaurs, iPods and Chevy Volts, progression inevitably gives way to versioning out. But I’ll never say, that’s just life. It’s my life. “Alexa, get lost.”