On a trip to Spain a few years ago, my husband and I landed in Madrid and went straight to the car rental desk, where the employee who was helping us looked at Ron’s full name on his passport and laughed out loud. Then she got up from her chair and, still laughing, began showing his passport to her colleagues around the room.

I’ve sometimes wondered how Ron’s parents looked at that tiny baby and thought, “Yes, we’ll call you Dingomanus Julianus Hieronymus.”

One of my sons says the name acquired cult-like status at university parties, where his friends, at some point in the evening, would begin to cheer, “Say the name!” My son would shout the name, and everyone would begin to chant in unison.

My other son once left a thank you note for Ron that said: “Dear Dingomanus, your Hieronymus-heart has helped me once again. It’s a good thing, or I would’ve had to kick your Julianus.”

Back at the car rental desk in Madrid, Ron and I were at an emotional crossroads, choosing how to respond. We could decide to feel offended, get angry, make a fuss, file a complaint. After all, passports are private, and we were tired from our flight and impatient to get our car.

Instead, we chose to laugh with them, because from their point of view, they were expressing legitimate amazement and joy. And because it’s more effective, and it actually requires less energy, to look for the good in people instead of believing they’re wrong.

Everyone has a best-self version.

Some best-selves seem to be more deeply hidden than others, but we’ve all got one. If we overlook a person’s best-self, and instead insist on seeing what he or she is doing that annoys or saddens or angers us, that’s what we’ll keep getting. Because, when we decide about people that “this is who they are, and this is how they’ll always be,” our conclusion will perpetuate the thing we’ve concluded.

When we observe how people are acting, and it doesn’t please us, and we hang on to our beliefs about it, even though we’re feeling bad as we do it, nothing can change. Not the people, and not our perspective or our ability to have influence.

But if we will envision something different and begin to look for evidence of that, proof of change will show up. Because perspective changes first, then reality.

If we want to support the people around us in being the best they can be, the first step is to perceive them as that: their best-self versions. And we need to feel good while we’re doing it, to activate that perception of them – first in us, and eventually in them.

It’s only when we activate best-self attitudes and outlooks in ourselves first that we have any power of influence to call those qualities from others.

We can’t coerce people or create positive change through forced compliance. It’s cliché, but true. The only way to have influence is through example.

By enlivening our own best behavior, we may be able to inspire the same in others. They may take notice and think, “That looks good,” and then begin to manifest it themselves, which is how inspiration works.

A pivotal experience.

When Ron was a medical student in his early 20s, long before he and I met, he came home one evening and found a guy who’d had too much to drink urinating on the door of his third-floor walkup. Ron pushed the guy to stop him, and he fell against the doorpost, cut his nose, and then ran away.

A few hours later, when Ron was already in bed, the guy came back with a friend. Ron first heard glass breaking, then the two men running up the stairs, yelling. He was paralyzed with fear. They broke through his door, grabbed him and threatened to kill him.

Then something unique happened. Ron says that he felt a shaft of protection come down over him, like a presence. As if some part of him was observing the chaos, while inside he remained secure and detached.

The situation was still out of control. The first guy was gripping Ron, while the other blocked the doorway and shouted threats. Then Ron said to them, “I won’t fight you, but if you want to sit down, I’ll get you a drink and we can talk.”

That’s when something inside the first guy seemed to break, and he began to cry. Then the other guy softened as well. And the three of them ended up sitting in Ron’s living room, drinking beers and talking till dawn. Ron says that he questioned whether he should give them alcohol, but it was what they wanted.

The guy with the cut nose had been intent on revenge but realized that, had he gone through with it, he would’ve ended up in jail, instead of being the only one of his gang who still held a job. Ron listened for hours as the two men described their lives and gave him a peek into a world apart.

While encountering other people’s worst-selves, choosing to express our best-selves means – instead of calling them on it, demanding that they admit it and making them wrong – we coax them in the opposite direction, toward reconnection with their best-self versions, who they truly are. But we can’t do it unless we’re relating from that place inside ourselves.

Influencing interactions toward improvement begins with our beliefs. Because situations are stuck in our attitudes and expectations more than in other people’s actions. The person might as well be saying, “I’m not acting in the way that you want, but I’m acting in the only way that you’ll let me.” And we can say, “I have this rigid expectation of you, and you’re acting in the only way that my beliefs will let you, so we’re stuck in this way of relating – unless I change something.”

When change eludes us.

If we care more about what people are thinking about us, and how they are acting toward us, than whether we feel good, we open ourselves to reacting defensively and blaming others. And then, we’ll want them to change so that we can feel better.

If we believe that people have to act differently before we can feel good, we’ll try harder and harder to get them to change for us. But as we push harder against them, their behavior will grow bigger as we give it power.

Each one, on the two sides of an issue, is giving power to the other by pushing against. And though both sides lose in this kind of situation, the one that appears to win is usually the one who has been pushed against the hardest.

According to the I Ching, a student from a Showlin Monastery was sitting in meditation one day when he heard a scuffle out in the garden, which turned out to be a crane and a snake, fighting. The student observed as, over and over, the crane would strike out. And each time, the snake would protect itself by adjusting its position, moving in whatever direction necessary to avoid the crane’s strike. The two creatures kept at it for hours, until the crane was too exhausted to continue. And that’s when the snake attacked. The snake was finally able to overpower his prey, not through being active and assertive, but through yielding, adjusting itself accordingly to the crane.

It was an Aha! moment for the student. The strength of yielding is stronger than the strength of attack, and it’s possible to switch back and forth between the two: passive and active, yin and yang. So the student began to practice the movements – moving from side to side, yielding to an incoming force rather than meeting it with attack. And that was the birth of what would become Tai Chi.

Why choose the path of understanding and acceptance, instead of fixating on what we don’t like, needing it to change so that we can feel all right? There’s a freedom in going through life without enemies, without anyone who we’re at odds with, and knowing that no one can cause us to disconnect from our best-selves.

It will help to say, “I’m just going to make the best of things, the best of this circumstance, the best of this person. It isn’t the best I’ve had, but I’m going to make the best of it.” And as we do that, more and more of the best of things will show up for us.

Every moment is a crossroads.

To interact differently, we’ll need to retrain ourselves. We can’t keep repeating what we’ve been doing and expect anything to be different. We have to begin new, with a different attitude, perception and expectation. That’s how we activate in ourselves what we want to experience in others.

There’s a tendency to say, “If that person will stop doing that, I’ll stop seeing it.” But the truth is: If we’ll stop seeing it, that person will stop doing it. Does that mean they’ll become different? It means they’ll become different in our experience, or they just won’t show up for us anymore.

As we go through our day, and we see something that we don’t like, we instinctively prefer something else – it’s built into our nature to desire improvement in whatever areas aren’t working for us.

In that moment – when we see what is, and we want something else – we’re at an emotional crossroads. And our choice will determine what happens next. If we keep thinking and talking about, and complaining about, and pushing against what we don’t like, it will perpetuate.

But if we keep focusing on, and dreaming of, and aspiring to our improved preference, we’ll naturally go in that direction. And when feeling good is most important to us, more and more reasons to feel good will show up.

You can follow Grace de Rond on Instagram and at gracederond.com.

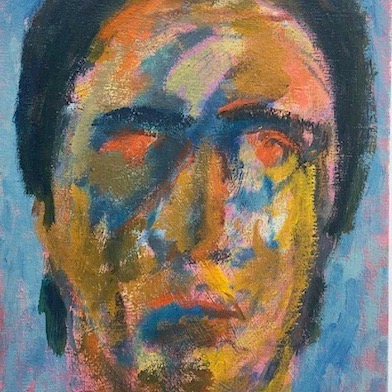

Pic by Mike Ricioppo.

@riciloco