This piece was first posted on Substack. To comment, please go there.

When I was in New York City I was talking to a colleague and happened to make a comment about how much of the work of public health is about establishing bureaucratic norms. My comment reflected how a core focus of our work is creating effective processes within institutions that support health—which is indeed the work of bureaucracy. My colleague responded by saying, “Wait till they call you a faceless bureaucrat.” This remark—which, perhaps, I should have seen coming—captures the disregard many have, intrinsically, for bureaucracy. The very word conjures blandness, redundancy, and red tape. This is reflected in representations of bureaucracy in film and literature, in the novels of V. S. Naipaul and Franz Kafka, and in movies like Office Space and the television show The Office.

So, bureaucracy is easily lampooned. But what, exactly, are we lampooning? Is it the reality of what bureaucracy does, or merely the reputation of bureaucracy—the outward trappings of what is, in fact, a complex and essential sector?

Merriam-Webster defines bureaucracy as:

This definition suggests three key features of bureaucracy: its members are unelected, (hence the “faceless” charge), yet can wield tremendous influence on the daily functioning of organizations. Bureaucracy is also characterized by hierarchy and rules, which are both core to the effective functioning of organizations and easily cast as oppressive foils to more freewheeling modes of group effort and innovation. Finally, within bureaucracy, rules and regulations run the risk of becoming self-reinforcing, there-for-their-own-sake vectors for redundancy, inefficiency, and waste. This speaks to another reason why bureaucracy is often regarded with suspicion, mockery.

With this in mind, I realize that, in doing what I am about to do—argue that bureaucracy is indeed essential for all we do, for all that promotes health, particularly during COVID-19—is defending what many consider to be indefensible: bureaucracy. But if health is generated by the world around us, bureaucracy, i.e., the systems and procedures that organize our world, is essential to health, hence it seems to me well worth understanding these systems and how to improve them. This means first accepting that they do have a function, and a necessary one. I want effective bureaucracies to ensure that our system of roads and attendant regulations do not result in unnecessary burden of death and disease. I want effective bureaucracies that build healthy parks and greenspace. So then, in keeping with the theme of these series of essays, can we look at the function of bureaucracy through a COVID lens and ask: what did we learn about bureaucracy in this moment? And how can we take what we have learned to make for better bureaucracy for better health?

Within public health, the COVID-19 moment has brought the features of bureaucracy into focus in different ways, as we have worked within bureaucracies to meet the challenge of the past year-and-a-half. During this time, it would be fair, I think, to say that bureaucracy’s record has been mixed—that bureaucracy, for all the good it has done, has also made some stumbles. In particular, the following three challenges have complicated our efforts to be maximally effective during the pandemic.

First, the bureaucratic structures in charge of communicating with the public at the national level have struggled to do so effectively. While much criticism has rightly been directed towards the Trump administration for the incoherence of its messaging around COVID, it is also true that the public health bureaucracy has, at times, presented the public with mixed messages around what to do during this crisis. This is the case now, for example, as messaging changes around masking and it is difficult to get a sense of public health speaking with a clear voice on the subject. It is also the case that bureaucratic messaging around the pandemic could sound, at times, moralizing and pedantic, undercutting its effectiveness. (I have written previously on moralism in public health here). This challenge of tone was perhaps informed by the tendency of bureaucracies to become “bubbles” in which policies and the terms in which policies are expressed become more reflective of the words and priorities of the bureaucracy than of the population it serves. This speaks to the broader challenge of when bureaucracies become, in a sense, their own constituencies, aiming to support their own internal continuity more than they may aim to support their outward-facing goals.

Second, the messy rollout of vaccine access has revealed bureaucracy’s limits in implementing solutions at scale in the midst of crisis. An organization like the CDC can study vaccines, make recommendations about their use, even assist in their delivery. But there is only so much it can do when it comes to persuading populations to actually get the shot. It is here, particularly, where the “faceless” character of bureaucracy can be problematic. The organizations making public health recommendations are staffed by people who were not selected by the public—this is true even when it comes to the White House, where just a handful of the decision-makers inside were directly elected to their posts. This can inform mistrust, a feeling, in the case of vaccines, of “Just who are these people who are telling me to put something in my body?” This difficulty is perhaps less a failing of those working within the public health bureaucracy and more a limitation of the structure of bureaucracy itself, one which has been on display during the pandemic.

Third, during COVID, bureaucracy has, to some extent, lived up to its reputation of creating, at times, a chaos of rules and regulations. The pandemic has been characterized by an ever-shifting fabric of laws and guidelines, shaped by the evolving nature of the virus and a changing social and political context. This context has posed a challenge for all of us, of course, not just for bureaucracies. However, bureaucracy’s structural predisposition towards complicated regulation and red tape has made it seem, rightly or wrongly, as less surefooted than, say, the efforts of private industry which did so much to quickly produce a COVID-19 vaccine. (This is not to say that private companies do not have their share of bureaucracy. However, companies are accountable to the demands of shareholders and the marketplace in ways which reflect a level of external accountability that many bureaucracies lack.)

I do not raise these points to argue against bureaucracy. On the contrary, a well-functioning bureaucracy is essential for supporting the public’s health. It is also core to supporting our embrace of the public institutions which are a hallmark of a society founded on the principles of small-l liberalism. For these principles to flourish, the institutions that are their outward face must function in a manner which inspires trust. For them to do so takes an effective internal bureaucracy.

What, then, does an effective bureaucracy look like?

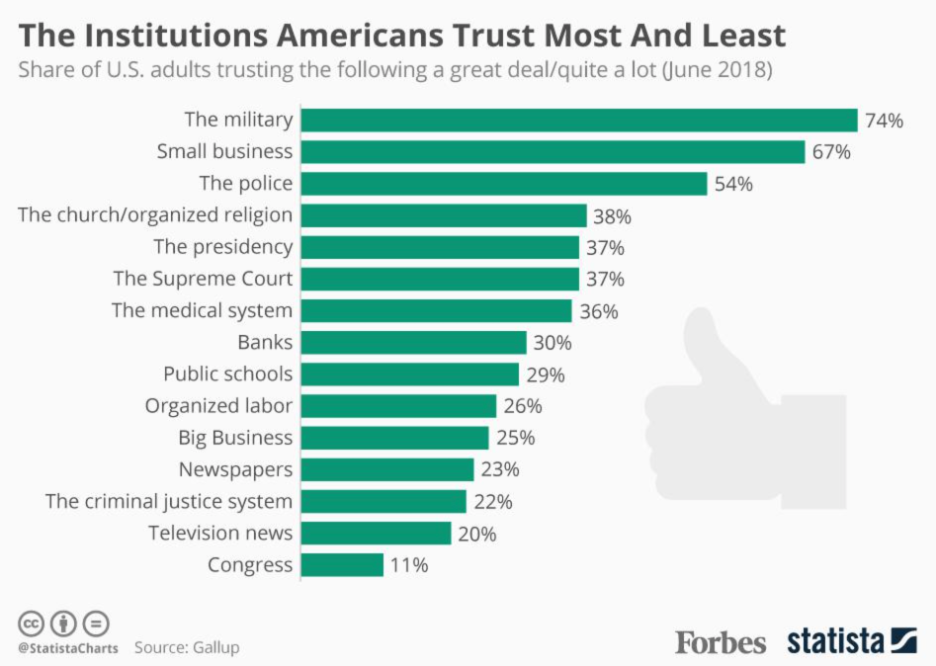

Effective bureaucracies must do what they are supposed to do, and do it well, fulfilling their basic operational functions (and, in doing so, raising the public’s trust in the overall worth of bureaucracies and the institutions they support). It is perhaps significant in this regard that the military remains the institution Americans trust most, one in which effective functioning is nonnegotiable, a matter of life-and-death.

How can we ensure bureaucracy does indeed maintain a high level of effective functioning? This question leads to a second feature of good bureaucracy—accountability. Organizations function best within an incentive structure which rewards effectiveness and discourages the lack of it. While bureaucracies may not be accountable to the voting public or the dynamics of the marketplace, there are a range of incentive structures which can be leveraged to support greater accountability. Then there are the demands of reality itself. Throughout COVID, for example, the demands of the moment have helped keep bureaucracy accountable, by creating steep human costs for failure. It is when bureaucracy is most insulated from these costs that it is least accountable. In public health, then, the very stakes of our mission can help support a higher level of bureaucratic performance. In this way, we can perhaps avoid the charge of being “faceless,” instead remaining outward-facing, responsive to the needs of the communities we serve.

Finally, bureaucracies work best when they are non-pedantic, embracing rules and regulations not for their own sake, but for their use as tools to support health and improve lives. This means resisting the self-perpetuating cycles of red tape which can sometimes characterize bureaucracies, in favor of a flexible approach, based on the needs of the moment. Core to this will be grounding our actions in the external data, rather than in internal bureaucratic priorities. This can help undercut the charge of arbitrariness so often applied to bureaucratic initiatives.

As an immigrant twice over I have had many encounters with bureaucracies, which have had real stakes for my future and that of my family. A defining feature of these encounters has always been a sense of whether the regulations and processes with which I engaged were genuinely in place to support a better status quo for all, or whether they were arbitrary, redundant. In the case of the former, it was always much easier to navigate the system. In the case of the latter, the situation could become more difficult. This supports a case that bureaucracy should always be rooted in the work of making people’s lives better, and that rules are meant to serve this improvement, rather than people living to serve rules. Because the bureaucrat really does play a key role in the creation of such a world. We need bureaucratic systems to work well, and, for all the ease with which they can sometimes be lampooned, few of us would want to be without the services they provide.