My home country the Philippines concluded midterm elections Monday. Around 45 million voters went to the polls to exercise their to right vote in what is deemed Asia’s first democracy. Similar to how the U.S. Midterms was marketed to the American electorate, it’s touted as a crucial turning point (like every elections) in our nation’s history. The New York Times billed it as a referendum on Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s policies and his war on drugs that has claimed 7,000 lives, mostly poor Filipinos. Netflix’s Hasan Minhaj sounded the alarm on the popularity of Duterte’s candidates, which would dilute the purpose of the midterms “as a check on the President’s power,” if they’re elected into office.

When I checked my Facebook feed late Monday morning in New York (the Philippines is 12 hours ahead), many of my friends were in mourning. Based on unofficial tally of votes, it’s expected that no opposition candidates will make it to the 12 senatorial seats up for grab. Amongst the presumptive senator-elects (all results are unofficial until declared by the Philippine Commission on Elections) is the daughter of a former Philippine dictator, a former actor-turned-senator charged with plunder, and a former police chief who publicly admitted he knows nothing about the Constitution.

“I am disappointed since many of us are very vocal about [our] stances in political issues in social media alone,” said John Ordonez, 21, a Development Communication student at the University of the Philippines. A student leader who I met in 2017 when he was the president of the ASEAN University Student Council. “But it got stuck only on our echo chambers and did not trickle down to the masses, to the grassroots who are in dire need to be educated,” he added. The Philippines is one of the most engaged electorate on social media, especially on Facebook. In the country’s 2016 presidential elections, 22 million Filipinos engaged on conversation about the elections online, creating more than 100 million conversations. In the Digital 2019 report by social media consultancy We Are Social and Hootsuite, Filipinos spend the most time on social media worldwide. Four hours and 12 minutes a day on average.

Remy Blumenfeld, a grief counselor, recently wrote for Forbes that some of his clients have been sad and angry, “because of Brexit, climate change or specifically the election of the 45th President of the United States.” He noted that their feelings “often border on grief” and that we could be sad, angry or depressed because of world events. In the Philippines Monday, social media posts calling the largely poor electorate as stupid and dumb, and pronouncements of hopelessness ran rampant. It was so prevalent that the Vice President of the Philippines, who is the leader of the opposition and campaigned for the losing candidates, put out a statement to stop name calling and “demeaning our fellow Filipinos”.

“We need a radical rethink,” said Gideon Lasco, a Filipino anthropology professor and newspaper columnist. “There are a lot of people who are demoralized [with the results]. But it’s a time to ask the hard questions, to reflect.” He noted that it maybe a point where people are realizing that they live in a bubble. He too was disappointed with the election results, but mentioned that it’s necessary to face the issues head on with courage and keep a “discourse of hope.”

Politics, as it is an exercise of choice, is divisive. It doesn’t help that where I’m from, we have a president that thrives on deepening our divide with his brand of rhetoric- indecent and profane. Americans deals with a similar challenge and our constant desire to stay connected make us willing recipients to the kind of things I’ve seen on my feed throughout the week. But it’s in these times that it’s crucial to take time off from fiery conversations and as Lasco noted, to reflect.

In Patti Clark’s Thrive Global entry, the Gift of Silence, she notes that silence and sleep allow time for our brain to cleanse itself. By taking time to reflect and rest, we allow our minds to delete things that constrain us from having a fresh perspective. Silence also improves the part of our brain that deals with memory, emotion and learning.

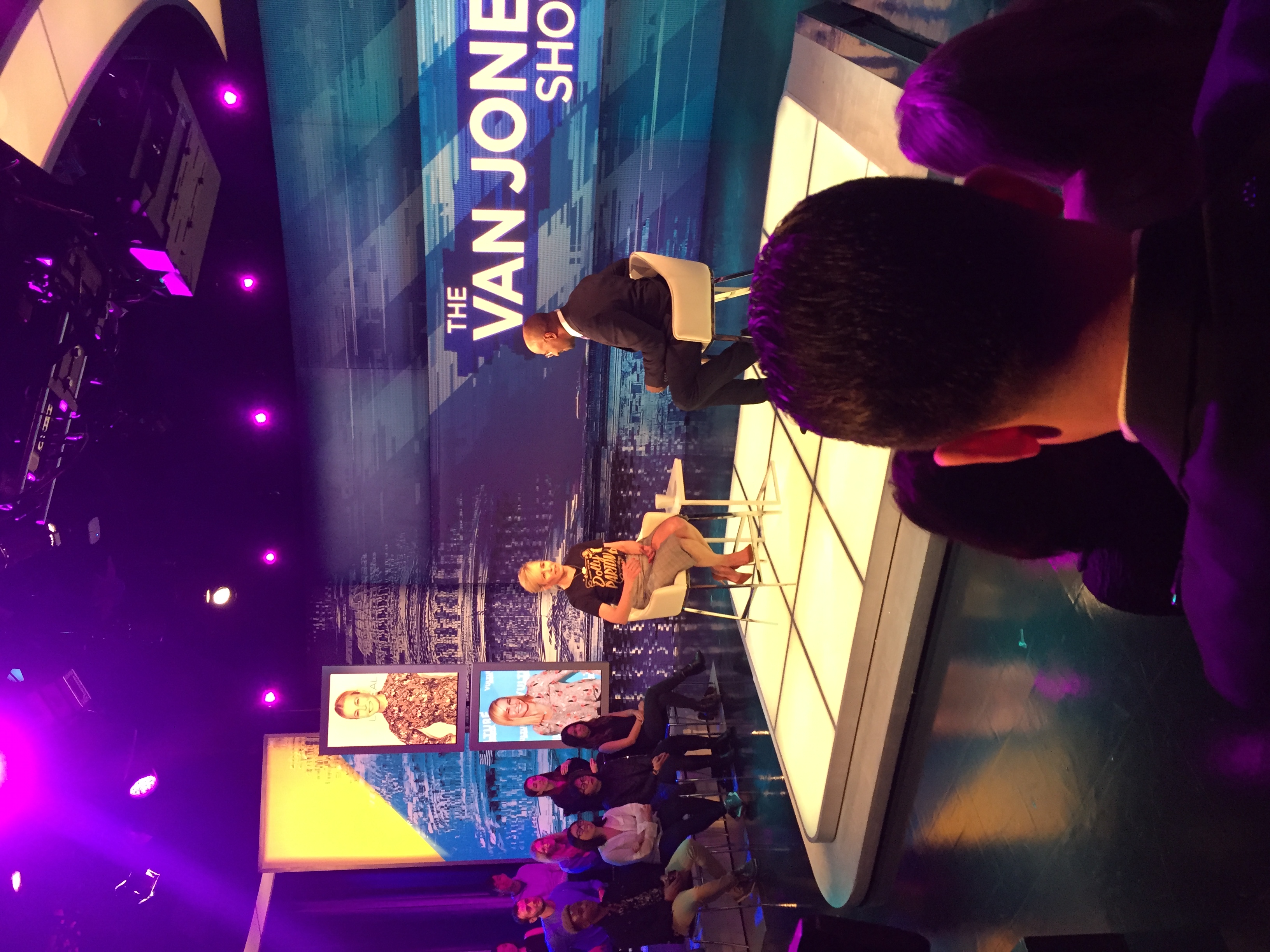

A few Fridays ago, I was at the final taping of the Van Jones Show at the CNN Studios in Columbus Circle (the network’s NY office is moving to Hudson Yards) where Chelsea Handler described how she needed to go into therapy after Donald Trump was elected president. “I had to get my life back,” she said. “I want to be optimistic and I want to be positive and I can’t watch the news on a loop like I use to, I can’t read the news on a loop like I use to, because I want to be in a state of action, not reaction.”

We can’t all afford therapy like Chelsea, but we can step back from the conversations and give ourselves the gift of silence. It may lead us to engage with those who differ from us and even prepare us for what could be greater challenges ahead.