Amitha Kalaichandran, M.D.

Dr. Neel Desai is a primary care physician based in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky. He is a contributing member to The Happy Doc podcast. He wrote a book called The O.I. Connection about the rare condition osteogenesis imperfecta, a rare genetic condition of faulty collagen and bone synthesis [summary of condition]. Dr. Desai spoke with me in September from Fort Mitchell, Kentucky.

We connected because I was working on a ‘medical mystery’ article about O.I., and had, by chance, come across the Happy Doc podcast, which I loved. But you had an interesting journey in medicine that prompted you to co-develop the podcast. Share a bit of that with readers.

I’ve been working as a primary care doctor for 15 years, and about 5 years ago, it got to a point where I was becoming frustrated with medicine. I was losing autonomy to administrative burden and inefficient electronic medical records. So I wanted to look for ways to build (digital) creativity into my life and regain some autonomy. Writing my book and being part of the podcast led me to some powerful insights. I realized creative pursuits helped me address frustrations with the current medical system. I also observed another common pattern: the rigorous process of becoming a physician can suck the creativity out of doctors in training. Conversely, we observed doctors, residents, and medical students working on a creative endeavor regained energy and fulfillment in their training, as well as in their personal and professional lives.

What is the HappyDoc Podcast?

The Happy Doc Podcast was started by Dr. Taylor Brana, as a third-year medical student, at a time when he was becoming disillusioned with his medical training, and as a result was just very unhappy. He began asking the question, ‘are there any happy doctors out there?’. Most of what he was seeing in his attendings was not good: burnout, lack of joy in medicine, and just disillusionment with their current station in life. He connected with me online, seeing that I had been out in practice, and asked me if I was happy. I had a unique answer to that question (I was happy when it came to initiatives aimed at educating the public about OI through modern technology ). He asked me if I wanted to join his podcast. The aim was to find happy physicians, discovering what helped keep them fulfilled in their work, and give listeners practical tips to do so in their own lives. I agreed to partner with Taylor and became the guest recruiter for the podcasts, and I also run social media engagement.

Let’s talk about what happened in Fall 2008 which led to your interest in O.I.

My wife and I were trying to conceive our first child and she had two miscarriages prior to this third pregnancy. This third one, a son, had made it to 17 weeks. During the ultrasound, the normally chatty ultrasound tech looked at the left femur (thigh bone) and fell dead silent. She abruptly left the room. She came back with the Ob/Gyn on call. He pointed out our son’s left femur was curved and not growing. He recommended we see a maternal-fetal specialist to set up an amniocentesis. We saw the specialist the next day. I’ll never forget how she delivered her diagnosis and prognosis: she said the findings were consistent with a skeletal dysplasia incompatible with life. She shrugged her shoulders, and said “I’m just being honest.” And left us in the room overwhelmed, heartbroken, shocked, and devastated. lt’s a great teaching point for any medical professional. Don’t ever deliver news that a person’s loved one is going to die without some compassion. That life changing moment prompted me to write an ebook called “The O.I. Connection,”. I found writing was very cathartic for me, helped to process my emotional trauma, and accept my son’s diagnosis. It also inspired me to help others in similar circumstances by bringing together resources for other OI families and caregivers in a practical and interactive way.

What can you share about getting to your ‘new normal’ after that diagnosis

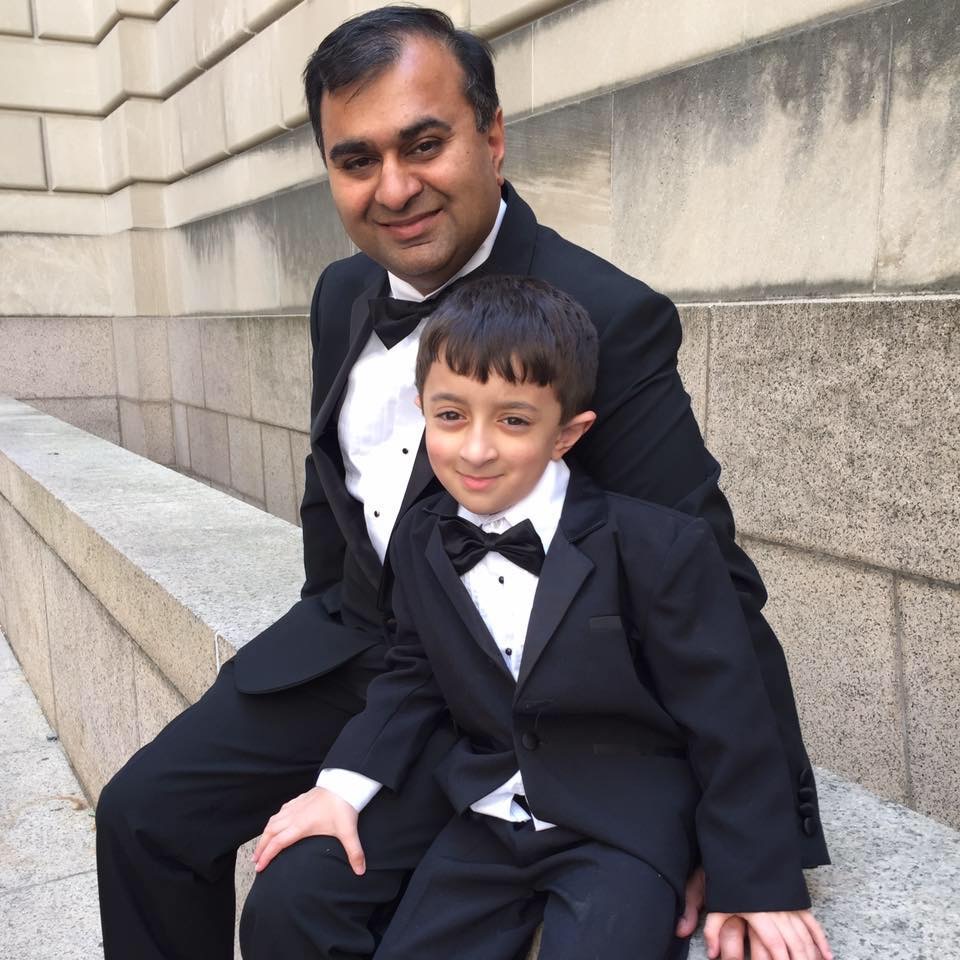

My wife and I were obviously stunned with the diagnosis. But we wanted to educate ourselves as much as possible about OI. We found an online OI family community of support on Yahoo health groups. The group included several health professionals, physiotherapists, and an emergency room doctor. They had children with OI and first hand experiences dealing OI. They gave us hope as they had successfully navigated the road ahead of us. They told us about revolutionary treatments for O.I., specifically, medications like intravenous bisphosphonates to prevent fractures and reduce pain, as well as telescoping rods which expand like curtain rods to straighten out the bones. They educated us on how these interventions help children gain more strength to grow, improve function, activity, and have a happier and healthier quality of life. Ethan was born with at least 7 fractures (unknown if he had more). He required the rods, the medication, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and started these early after birth. By 18 months he took his first steps with a walker. By 2 years old, he was running independently. It’s interesting, because as difficult as all this was, and still can be, at 10 years old today he can walk, swim, run, jump, dive, and dance. He still has to use his walker or wheelchair occasionally for safety or longer distances. He also academically functions at a higher level. He’s really into computers and space, for instance. I think even if there are physical limitations, many of these kids often adapt with their minds.

What is the biggest misconception about being a parent with a child with a chronic condition. Has it changed how you see your own patients?

The last thing any child with a chronic condition like O.I. wants is pity. What they want is compassion, understanding, kindness, dignity, and respect. A lot of people also assume that the subject is off limits for discussion, but we as an OI family embrace curiosity and asking questions, which is how all of us do better. I want people to ask questions and not be afraid to ask questions. I think keeping it taboo causes more problems. Asking questions leads to more understanding and acceptance. This goes for children with OI and answering their questions about OI as well. In regards to answering a child’s question about feeing less than or bad about why they have a chronic medical condition, I use the example of a parent I know explaining O.I. to her daughter with OI. She likens it to having blond hair or brown eyes or a birthmark: it’s just something you have, and nothing to be ashamed of. OI or any chronic illness can be hard as it affects how a family functions, but it can also affect marriages, jobs (especially with needing to take time off for fractures, surgeries, doctor, therapist, hospital visits), and can be very isolating and lonely for all involved. So one of the core lessons for me personally and professionally is the power of having a very strong supportive community to communicate with.

Switching gears how has this experience helped you approach your work as a doctor interested in advancing change.

All of this has really made me value strong communities. The role of community, as in having strong support networks and teams, is really important, and The Happy Doc community has been a huge part of that for me personally. A more proactive, as opposed to reactive, approach is really powerful as well.

In regards to advancing change, I think it’s time for us all to evolve in medicine. From what I’ve seen, it’s like medicine is dated and still stuck in the 20th century: there’s so much resistance to being innovative — poor EMRs, rigid traditional hierarchies, and using technology from the 20th Century (pagers, fax machines, etc) are barriers to where we could and should go. It’s 2019, and it’s time to practice medicine in the century we live in. We should embrace being proactive, innovative, and collaborative. We do this by amplifying what we value most: meaningful human connections. This occurs by reconnecting with our colleagues, our communities, and most importantly, with ourselves.

I use an analogy of it being like the medical profession was in the desert for most of the 20th Century, but now we’re in the 21st Century rainforest. The world expects us to just adapt to all the rapid changes over the last 20 years and thrive. But we can’t do this if there is immense inertia and if we don’t value questioning, curiosity, and creativity. Having outside interests – like podcasts or journalism—and integrating those creative outlets is important to develop current and future systems for the 21st century.

What does thriving mean to you?

Thriving means living your best life on your terms. Playing and loving your game unapologetically, unconditionally, and on your terms. Loving what you do, doing what you love. Waking up so energized that you can’t imagine doing anything else. And paying it forward and sharing your good fortune with the ones you care about most through the ups, the downs, and all the in betweens.

What are you most looking forward to now in general?

Creating a healthier, happier, wealthier, and wiser medical education system. A system where as healthcare professionals and patients, we are energized, enlightened, connected, and inspired. And most of all, to just enjoy the serendipity of the journey to the unknown and connecting to amazing people all over the world.