In the South Central area of Los Angeles, the Harvard Park neighborhood has long had a reputation as one of the toughest neighborhoods in LA County.

But things are changing. In September, the Los Angeles Police Department placed about 10 more officers in the park itself as an expansion of its Community Safety Partnership. The goal is for their presence alone to help make a difference, with the chance for residents to trust them even more once they get to know them.

My organization, the American Heart Association, got involved, too. We set up a pilot program with the LAPD and the Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks that encourages officers and residents to walk together on Saturday mornings, giving them another way to bond. The second and fourth Saturday of each month also include health screenings.

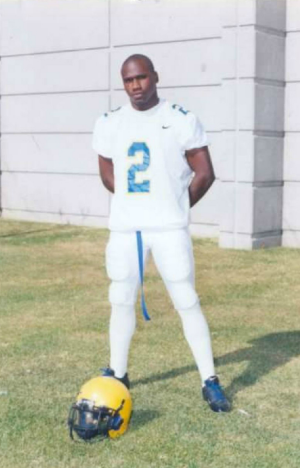

Marcus Whitehead is one of the LAPD officers assigned to Harvard Park. He had so much fun at the inaugural AHA event that he was excited to return the next time. He wandered over to the health screening area and, just for the heck of it, strapped a blood pressure cuff around his arm.

***

At 34, Whitehead still looked like a guy who’d played college football, even if the uniform might now be a bit snug.

Long shifts and a long commute often resulted in Whitehead eating what he could, when he could. Fried food became a staple in his diet. He drank at least one soda per day. He tried avoiding other sweets, though, because diabetes runs in his family.

Whitehead was a semi-regular at the gym. On good weeks, he went twice, putting in 2.5 miles on a treadmill each time.

He had a physical exam each year and never had a problem with his blood pressure. He had no family history of BP problems, either, but whenever he was at the pharmacy and nobody was using the machine, he liked to check his number. They were always good.

But on this Saturday morning in Harvard Park, the nurse said his BP was 160/130 – well into the danger zone.

It was so out of whack that she waited a few minutes and took it again.

The numbers came out even higher.

***

The nurse gave Whitehead a quick lesson about the dangers of high blood pressure, also known as hypertension, explaining that it ups his risk of heart disease and stroke.

She recommended he watch his diet and get more exercise. Most of all, she recommended he see a doctor.

About 10 days later, Whitehead hadn’t gotten around to a checkup when he felt a mild headache at work. This had been happening from time to time over the past few months and he always figured it was because of the stress at his job. He never thought much of it because medicine always helped.

Only this time, the headache began to pound. He became nauseous and light-headed. He thought he might pass out.

“Then I started to put things together,” he said. “I realized this hypertension thing was probably why my head was always hurting. It all made sense.”

Whitehead went straight to a doctor.

***

Sure enough, his blood pressure was even higher than it had been at the park.

A variety of tests turned up no other problems. That was good news. If he could control his hypertension, everything else should improve.

Whitehead took the next two days off work, followed by three scheduled days off. He used that time to commit to a new lifestyle.

He stopped drinking soda and started drinking a lot more water. He’s cut way back on fried foods and become more of a regular at the gym.

The headaches are gone, so he knows it’s working. He also knows there is more work to be done.

While he’s gone from stage 2 hypertension (140 or above for the top number) to stage 1 (130-139), he still needs to get through the elevated range (120-129) before dipping down to normal (less than 120).

***

Back on the beat, Whitehead not only attends the AHA event at Harvard Park, he’s a shining example of the difference it can make.

The event is part of an initiative called Community STEPS, with the acronym standing for Strategic dialogue That’s Empowered by Public Safety. It was created by Eric Batch, a vice president of advocacy in our Los Angeles office, during a nationwide challenge to create a new, replicable program to improve the health of communities. Out of 110 submissions, STEPS received the grand prize of a $100,000 budget to make it a reality.

“This program was set up to be beneficial for the community, but it helps us officers as well,” he said. “If it wasn’t for STEPS, I may have never known my situation. I’m proof that it works.”

The LAPD’s Community Safety Partnership program he’s part of is working, too.

There hasn’t been a single homicide in the area since Whitehead and the other additional officers arrived.

“It’s no stretch to suggest the feeling of safety they’ve brought is behind the added traffic on the walking path, participation being up in sports leagues and bigger crowds at community events,” said Austin Dumas, the director of Jackie Tatum Harvard Park.

***

Whitehead shared his story at a local AHA board meeting and he’s sharing it here in hopes of inspiring others to learn more about their health and to take action.

The experience also has given him a new perspective on his own life.

As a police officer, Whitehead is well aware of his mortality. He goes to work every day knowing he may never get to go home to his 4-year-old son and 2-year-old daughter.

He used to envision that worst-case scenario being the result of violence.

Now he realizes the culprit could be diet, stress and a lack of fitness.

“I’ve got to get a handle on this,” he said, “to make sure I’m around for my kids.”