“That is just such a sad story,” one of the girls was saying, leaning in and eager to console (or so I thought). “I can’t believe what your family must have gone through,” exclaimed another, with sympathetic eyes.

Lawrence, a fellow Tel Aviv University exchange student like everyone at the cafeteria table, absorbed this tidal wave of sympathy with a stoic melancholy he seemed at labors to sustain. Lawrence was Canadian.

“I was telling them about my dad,” he explained, in what I recognized as a gambit to milk whatever it was some more. “He’s an Auschwitz survivor, eh? It sure was brutal over there.”

“You must be very proud,” I replied.

“Sure! Wait. Why?”

“Well, your dad went to Auschwitz. It’s like the Harvard of concentration camps.”

Yes, yes, I know.

In my recollection, sudden silence sucks the air out of room. The girls stare at me in shock. “Oh! My! God!” exclaims the one who is proudest in her affront. “Did. He. Just. Say. THAT!”

I want to think that this was the moment of epiphany, when I had a clear vision of future. Of the timid and timorous world we now inhabit decades later. A world in which some treat offense as worse than physical assault. I want to think that I’d be reckless enough to crack the same joke today.

I can be sure of neither. But I do know that the memory came rushing back at me this week, untroubled by the years, with the blessed return of Curb Your Enthusiasm. It is the vehicle of a completely difference Lawrence: comedian (and Seinfeld co-creator) Larry David, who I think would have appreciated my thoughtless, stupid, insensitive remarks.

After all, this is the Larry David who some years ago opened a Saturday Night Live monologue by ruminating about the logistics of romance in concentration camps.

The episode “The Survivor” featured a refugee of the Nazi genocide competing for tragedy credit with a hunky graduate of the eponymous reality show. “I was in a concentration camp!” cries the old man. “You never suffered even one minute of your life compared to what I went through.” The youth is unimpressed: “We had very little rations, no snacks… I couldn’t even work out (and) they certainly didn’t have a gym.”

Larry’s insensitivity actually covers quite a range. One edgy caper features an ex-girlfriend who invites Larry to an incest support group only to have him discover that the trauma stemmed from verbal advances from a stepfather who was not only younger than her mother but also younger than herself (Larry wonders whether this counts). In another instance he struggles with whether it is legitimate to break up with a person about to receive a cancer diagnosis (he must outrun the doctor to the house).

In “Palestinian Chicken,” an attractive Palestinian woman is amorously inspired by Larry’s craven insistence that a certain Funkhouser remove his yarmulke prior to entering a chicken restaurant full of Arabs.

“You’re a Jew, yes?” “Big Jew,” Larry replies, sensing the coming of a reward.

“Big Jew — and you still told him to take off his Jew cap. What’s your name?”

“Leib. Son of Nat. My friends call me Larry.”

If Larry seems offensive to you, then we agree. But I am not shocked by offense. Offend me all you want, whoever you may be. I hate cruelty but humor is the spice of life; it is a balance and the humor side of it needs space. There should be limits, I suppose, but I’d be careful with these limits. Policing appropriateness and granting license based on group identity soon leans illiberal and doctrinaire. That way lies the Ministry of Truth.

I watched the first episode of Season 11 as soon as I could, on principle, and was not disappointed. The philosophical explorations (spoiler alert) include whether it is OK to ask a sufferer of dementia (or is he pretending?) for the return of a $6,000 loan.

My own father survived a labor camp in Romania, a Nazi-allied country where half the Jewish population perished in the war. The way my late dad told the tale, he made it by mastering ping pong, impressing his Nazi masters, but always letting them somehow win.

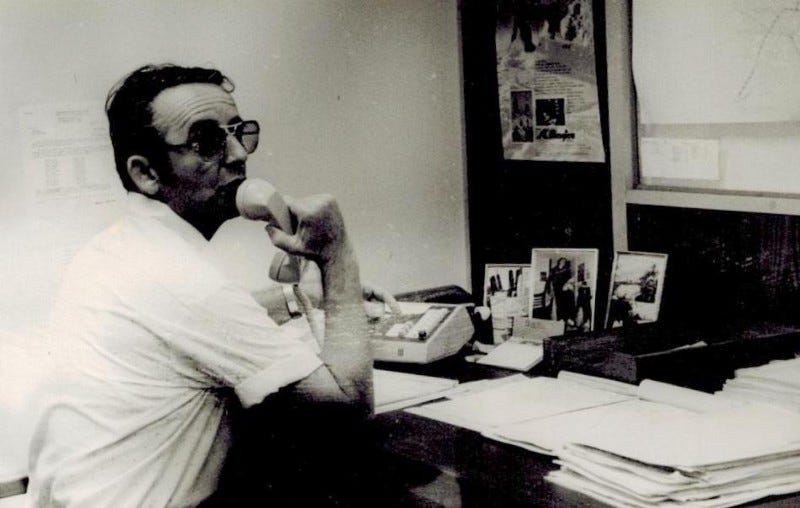

Years later, in Philadelphia, he would work Saturdays for overtime at the civil engineering firm where he started as a draftsman and would retire as VP. Amid rows of desks he organized a ping pong table, and on that table he taught his little boy the secret of a killer underspin serve. It would in time bring me some advantage, less dramatic than his but still profound. “This game with these little balls,” he would say in Romanian tones, “this it’s a very important game.”

In the cafeteria, it suddenly struck me that the ping pong story might win some sympathy for me, as well. But I hesitated too long: Does it count, compared to Auschwitz? The potential audience dispersed.

I decided then to find my friends among the Israelis, far less inclined to take offense. And that is how I met my wife.